They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

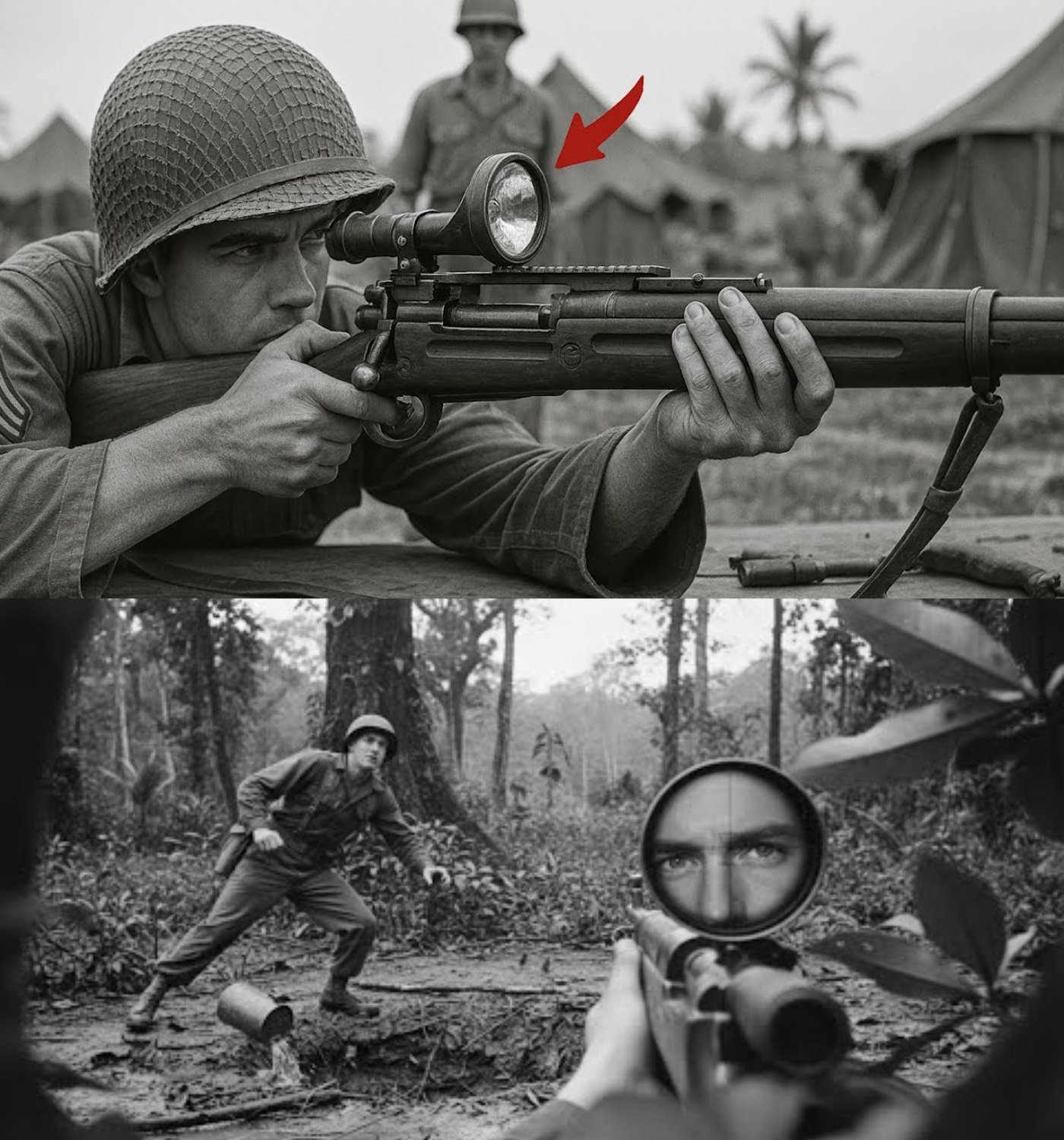

At 9:17 AM on January 22, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese bunker west of Point Cruz, his heart racing as he peered through the scope of a rifle that had become the subject of mockery among his fellow officers. Just 27 years old and an Illinois state champion marksman, George had zero confirmed kills to his name, but today, he was about to change that narrative.

The Japanese had fortified Hill 382 with 11 snipers, and in the past 72 hours, they had killed 14 men from the 132nd Infantry Regiment. George’s commanding officer had derisively called his rifle—a Winchester Model 70 with a Lyman Alaskan scope—a “toy.” The other platoon leaders had dubbed it his “mail-order sweetheart.” But now, with the lives of his comrades hanging in the balance, George was determined to prove them wrong.

The Weight of Expectations

When George had unpacked his rifle at Camp Forest in Tennessee, the armorer had looked at him quizzically, asking whether it was meant for deer or Germans. George had explained it was for the Japanese. But before he could use it in battle, he had to wait for weeks while his rifle sat in a warehouse in Illinois, delayed by military logistics. Finally, in late December of 1942, a supply sergeant handed him a wooden crate marked “fragile.” Inside lay the rifle he had saved two years of National Guard pay to buy.

The Winchester weighed 9 pounds, and with the scope, it added another 12 ounces. In contrast, the Garand issued to every other man in his battalion weighed 9.5 pounds with no magnification. George’s rifle was bolt-action, capable of five rounds, while the Garand was semi-automatic, firing eight rounds. Captain Morris had ordered him to leave the “sporting rifle” in his tent and carry a “real weapon,” but George had stubbornly carried it anyway.

The 132nd Infantry had relieved the Marines on Guadalcanal in late December 1942. The Marines had fought fiercely since August, taking Henderson Field but struggling to clear the Japanese from the coastal groves west of the Matanakau River. Hill 382 stood 1,514 feet tall, a strategic point fortified by the Japanese with 500 men and 47 bunkers.

Into the Fray

On January 19, a sniper killed Corporal Davis while he was filling canteens at a creek. The following days saw more casualties, with three men dead in a single day, one shot through the neck from a tree that the patrol had walked past twice. The battalion commander summoned George that night, expressing the urgent need for someone who could shoot. He wanted to know if that “mail-order rifle” could actually hit anything.

George explained his credentials as the Illinois State Champion at 1,000 yards in 1939, boasting impressive groupings even at 600 yards with iron sights. The commander gave him until morning to prove it. That night, George meticulously cleaned his rifle, ensuring it was ready for action.

At dawn on January 22, he moved into position in the ruins of a Japanese bunker his battalion had captured three days earlier. The bunker overlooked the coconut groves west of Point Cruz, where intelligence had indicated Japanese snipers operated from the large banyan trees. These trees could reach 90 feet tall, allowing a sniper to remain hidden all day.

The First Kill

As George settled in, he began scanning the trees through his scope, the jungle alive with sounds of nature and distant artillery. At 9:17 AM, he spotted movement—a branch shifting without wind, revealing a dark shape in the fork of a banyan tree 240 yards away. A Japanese sniper was watching the trail where his battalion had been moving supplies.

George adjusted his scope for wind and controlled his breathing. He squeezed the trigger, and the Winchester kicked against his shoulder. The shot cracked through the jungle, and the sniper jerked and fell, tumbling through the branches to the ground below. George quickly chambered another round and kept his scope trained on the tree, waiting for the spotter to reveal himself.

At 9:43 AM, he found the second sniper, lower in a different tree, retreating after hearing the shot. George aimed and fired, hitting the sniper as he fell. Two shots, two kills. Word spread through the battalion, and men who had mocked his rifle now wanted to watch him work. But George refused; spectators drew attention, and attention drew fire.

The Japanese snipers adapted after the fifth kill, becoming cautious and ceasing movement during daylight. George spent the afternoon scanning the trees, but nothing appeared. At 4:00 PM, he returned to battalion headquarters, where Captain Morris was waiting for him, no longer mocking but instead eager for results. He wanted George back in position at dawn.

The Rainy Days of Battle

January 23 began with heavy tropical rain, turning the jungle floor into mud and reducing visibility. But George used the time to move to a new position, not the bunker or the fallen tree—somewhere the Japanese would not expect. He chose a spot in a cluster of large rocks that provided good cover and overlapping fields of fire into the groves.

As the rain slowed, George began glassing the trees again. At 9:12 AM, he spotted his first sniper of the day, a Japanese soldier positioned in a palm tree 190 yards out. This sniper was lower than usual, only 40 feet up, which puzzled George. He aimed and fired, and the sniper fell.

However, the Japanese response was immediate. Mortars began hitting the area around his bunker, forcing George to relocate to a different position. The dynamic had changed; this was no longer target shooting but a deadly duel.

Over the next few hours, George continued to engage Japanese snipers, killing his seventh and eighth targets. Each shot was precise, each kill a testament to his skill. But as the sun began to set, the Japanese adjusted their tactics again, sending more snipers to hunt him down.

The Final Confrontation

On January 24, George found himself in a precarious situation. After eliminating several snipers, he realized he was being hunted. The remaining Japanese snipers were more cautious, and George knew they would be waiting for him. The tension was palpable as he scanned the trees, looking for movement.

At 10:06 AM, he spotted a Japanese soldier crawling through the underbrush, moving toward his last known position. George remained still, waiting for the right moment to strike. When the soldier reached the rocks, George fired, hitting him squarely. But as he worked the bolt, he heard voices approaching—the unmistakable sound of multiple soldiers moving toward him.

George knew he had to act quickly. He dropped back into a crater, submerging himself in muddy water as bullets began to fly overhead. The Japanese soldiers were closing in, and George’s heart raced as he prepared for the confrontation.

The Climax of Courage

In a desperate bid for survival, George waited for the right moment. As the soldiers moved past his position, he rose, firing his rifle at the nearest target. He quickly dispatched two soldiers, but the remaining soldiers were now aware of his presence, and the firefight escalated.

With only two rounds left, George knew he had to make every shot count. He aimed carefully, taking out the last of the soldiers before the chaos subsided. Sweat dripped down his brow as he surveyed the aftermath of the battle, realizing he had neutralized 11 Japanese snipers.

But the fight was far from over. As George began to move back toward American lines, he heard the unmistakable grinding of a tank engine. A Type 95 Hago light tank was advancing toward his position, and he knew he had to act fast. With one rocket left, he aimed carefully and fired, striking the tank’s engine compartment and igniting the fuel inside.

The explosion sent flames shooting into the air, and George watched as the tank crew scrambled to escape. With the last of the Japanese defenses in chaos, George made his way back, exhausted but triumphant.

A Legacy of Valor

By the end of the day, George had killed 11 Japanese snipers, a feat that would change the course of the battle at Point Cruz. His actions not only saved countless lives but also proved that individual skill and determination could overcome even the most entrenched enemy positions.

As he returned to his battalion, George was met with respect and admiration. The officers who had once mocked his rifle now recognized his courage and skill. He had transformed from a novice with a “mail-order” weapon into a hero who had single-handedly cleared the way for his comrades.

In the days that followed, George continued to serve with distinction, training new recruits and sharing his knowledge of marksmanship and tactics. His experiences in the jungles of Guadalcanal and beyond shaped his understanding of warfare, and he became a mentor to many.

George’s legacy lived on long after the war ended. He returned to civilian life, but the lessons he learned in combat remained with him. He often reflected on the importance of individual initiative and the power of a single soldier to make a difference in the face of overwhelming odds.

Years later, as he looked back on his time in the military, he realized that the true measure of a soldier is not just in the battles fought or the enemies defeated, but in the courage to stand firm and fight for what is right, even when the odds are stacked against you.

John George’s story is a reminder that heroism can come from the most unexpected places. With a rifle that had been ridiculed, he forged a path to victory, proving that determination and skill could overcome even the toughest challenges. His actions at Point Cruz will forever be etched in the annals of military history, a testament to the indomitable spirit of those who serve.