They Mocked His “Stupid” Grenade Trap — Until It Killed 23 Germans in 19 Seconds

On December 22, 1944, in the besieged town of Bastogne, Belgium, the air was thick with tension and the bitter cold of winter. Corporal Daniel “Danny” Reeves crouched in a frozen foxhole, his fingers numb despite wearing two pairs of gloves. He was making final adjustments to what his squadmates had mockingly dubbed “Reeves’s ridiculous Rube Goldberg”—an elaborate defensive trap unlike anything the 101st Airborne Division had ever seen. It consisted of 57 grenades connected by 23 trigger wires, strategically arranged to create a deadly cascade of explosions.

For three days, Reeves had endured relentless criticism from his fellow soldiers. Sergeant Harold McKenzie was particularly vocal, deriding the contraption as the “dumbest thing” he had encountered in two years of combat. “You’ve wasted three days building a grenade trap that probably won’t work and definitely won’t matter,” McKenzie scoffed. Lieutenant Peter Walsh echoed similar sentiments, urging Reeves to focus on reinforcing actual defensive positions instead of wasting resources on an elaborate trap.

But Reeves, a mechanical engineering student from Scranton, Pennsylvania, understood something his critics did not. He had spent his childhood watching his father, a mining engineer, design safety systems that prioritized redundancy and reliability. To him, the complex system he had constructed was not merely a collection of grenades; it was an integrated defensive mechanism designed to maximize effectiveness even under the harshest conditions.

The Design of the Trap

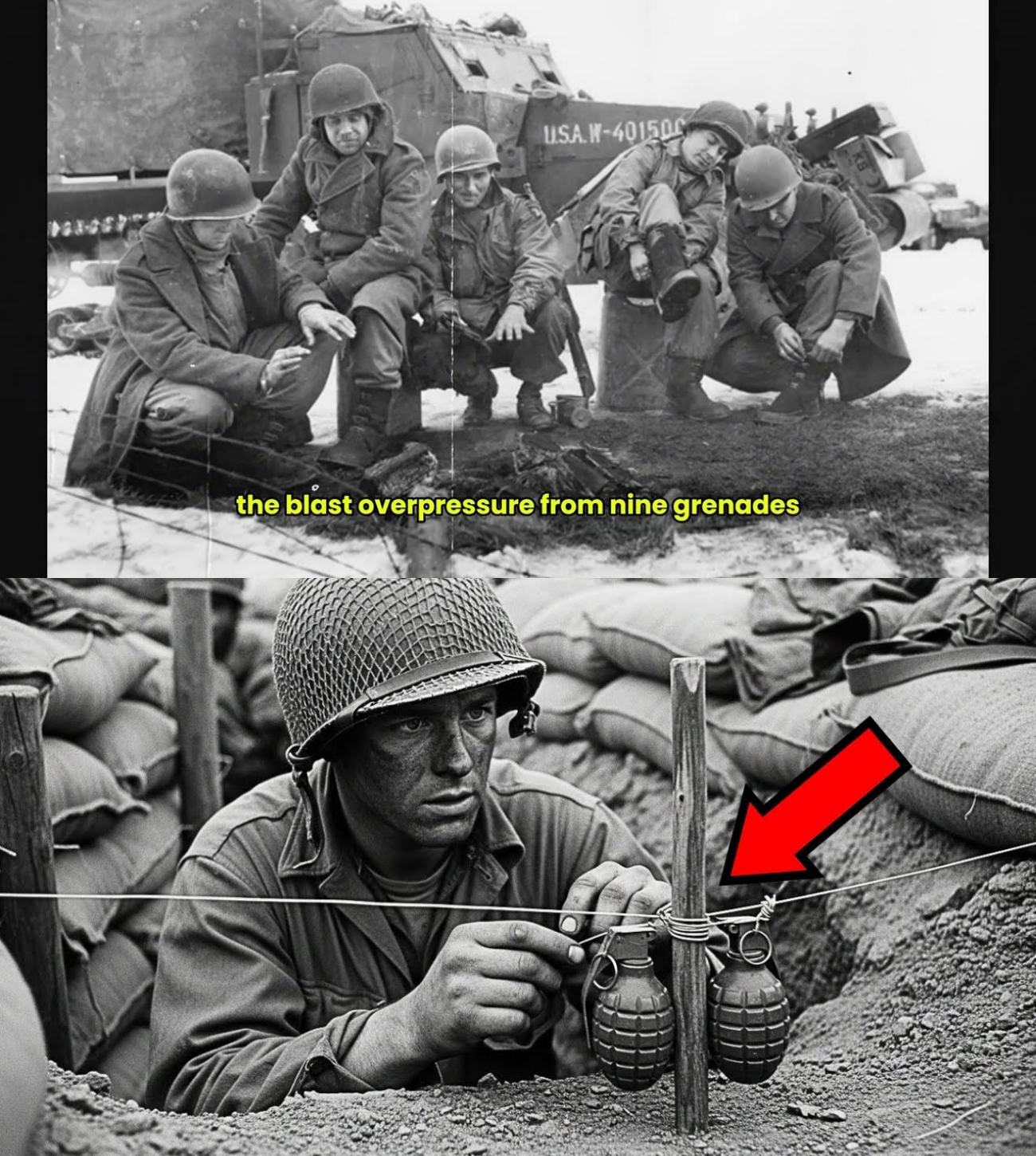

Reeves’s trap was meticulously crafted, employing principles of redundancy and overlap. The 57 grenades were positioned in nine overlapping kill zones arranged in three concentric semicircles. Each kill zone contained six to seven grenades, strategically placed at calculated heights and angles. The 23 trigger wires were arranged so that disturbing any single wire would initiate a cascade sequence, affecting multiple kill zones simultaneously.

Reeves had spent countless hours calculating the effective casualty radius of each M2 fragmentation grenade, which was approximately 15 meters. By positioning the grenades optimally, he aimed to create a kill zone covering around 900 square meters, ensuring that anyone unfortunate enough to enter would be hit by fragments from at least three separate explosions.

Despite his careful planning, explaining these intricate calculations to soldiers who were cold, hungry, and surrounded by German forces proved impossible. They wanted simplicity, not complexity. They saw his elaborate trap as a waste of resources, a foolish endeavor in the face of an overwhelming enemy.

The Calm Before the Storm

The criticism intensified on December 20th when German artillery began heavy bombardment of American positions around Bastogne. Each shell that landed near Reeves’s trap sent his squadmates into anxious speculation about whether his complex trigger system had been destroyed. Private James Morrison, who had nicknamed the trap the “stupid trap,” made a show of checking after each barrage, only to report back with a smirk, “Yep, Reeves’s stupid trap is still there. Still stupid. Still won’t work.”

As the situation grew more dire, Sergeant McKenzie approached Reeves with an ultimatum. “Corporal, General McAuliffe just told the Germans to go to hell. We’re not surrendering, which means we’re fighting. I need every man focused on defensive positions that will actually matter when the Germans attack,” he ordered, demanding that Reeves dismantle the trap.

But Reeves stood his ground. “Sergeant, with respect, I need 12 more hours. If the trap doesn’t work by 0400 tomorrow, I’ll dismantle it myself and distribute the grenades. But if it does work, it could break a German attack before it reaches our main line.”

McKenzie considered this. “What makes you think the Germans will attack through your sector?” Reeves explained that it was the weakest point in their defensive perimeter, the easiest approach terrain. Any competent German commander would identify this as the optimal breakthrough point.

Reluctantly, McKenzie agreed to give Reeves the time he needed. “12 hours, Corporal. If nothing happens by 0400 December 22nd, you dismantle that contraption. Clear?” “Clear, Sergeant,” Reeves replied, knowing that the intelligence he had received indicated a major attack was imminent.

The Night Before the Attack

That night, Reeves made final adjustments to his trap, testing each trigger wire and verifying each grenade’s position. The temperature had dropped to 14°F, making metal brittle and increasing the risk of failure. But Reeves had designed the system to withstand such conditions, employing techniques his father had taught him about ensuring mechanical reliability in extreme cold.

At 0300 hours, Reeves heard the unmistakable sound of tracked vehicles in the distance—German armor moving into position. He alerted his squad and settled into his foxhole to wait. The trap was ready; either it would work, or he would be deemed the fool who wasted three days building a useless contraption.

At 0400 hours, German artillery began a preparatory bombardment of the southern perimeter. The barrage lasted 17 minutes, pulverizing American positions with high-explosive shells. Reeves pressed himself into his foxhole, praying that none of the artillery hits would detonate his carefully positioned grenades prematurely.

As the bombardment ceased, a tense silence fell over the battlefield. Reeves knew what came next: the infantry assault. German soldiers would advance under the cover of darkness, attempting to infiltrate American lines before defenders could respond effectively.

The Attack

At 0415 hours, Reeves heard movement ahead—footsteps in the snow, multiple soldiers attempting to move quietly but unable to completely silence the crunch of frozen ground. He estimated at least 20 men, possibly more, advancing directly toward his position through the exact approach route he had predicted.

As the first German soldiers entered the outer edge of his trap’s kill zone, they moved carefully, weapons ready. One soldier knelt to examine something, possibly looking for mines or other obstacles. Unbeknownst to them, they had advanced past the outer trigger wires without detecting them, thanks to the darkness and cold that concealed Reeves’s carefully camouflaged wires.

Suddenly, the lead German soldier took another step forward, his boot catching on the primary trigger wire. The tension released, and what happened next occurred in exactly 19 seconds—a sequence that would change the course of the battle.

The Cascade of Explosions

The primary trigger wire released three M2 grenades positioned in the outer ring. These grenades detonated simultaneously, triggering a cascade of explosions that would devastate the German patrol. The blast from these three grenades set off two backup wire systems Reeves had ingeniously designed.

One backup system utilized a pressure release mechanism that Reeves had constructed using canteen cups filled with gravel. The blast wave displaced the cups, releasing tension wires connected to six more grenades in the middle ring. The other backup system employed heat-sensitive triggers salvaged from flare mechanisms. The thermal pulse from the initial explosions heated wire loops to their release point, dropping six additional grenades from elevated positions.

In total, nine grenades detonated in rapid sequence, creating a wall of fragmentation that swept through the German formation. But the cascade was just beginning. The blast overpressure from the initial explosions triggered pressure-sensitive mechanisms that released tension wires connected to 15 more grenades positioned throughout the middle and inner rings.

The remaining German soldiers, those still alive after the initial blasts, attempted to scatter, but Reeves had anticipated this. His grenade placement was designed to channel survivors toward the center of the kill zone, where the highest concentration of explosives awaited them.

At 0417 hours and 22 seconds, the inner ring detonated, unleashing 18 grenades that created a concentrated killing field at the center of the German formation. The final six grenades, positioned at the edges of the kill zone to catch fleeing soldiers, detonated at 0417 hours and 28 seconds, triggered by vibration-sensitive mechanisms Reeves had built.

In total, 54 of the 57 grenades functioned exactly as designed. The overlapping blast pattern meant that the three grenades that failed to detonate due to defective fuses were irrelevant, as their intended kill zones were covered by surrounding explosions.

The Aftermath

When the smoke cleared, Sergeant McKenzie climbed out of his foxhole and stared at the devastation. The ground where the German patrol had been was torn apart, littered with equipment, weapons, and bodies. Not a single German soldier had survived.

McKenzie approached Reeves’s position, his expression unreadable. “How many grenades did you use?” he asked. “57, Sergeant. And how many Germans?” Reeves had been counting bodies while waiting for his sergeant to arrive. “23 confirmed, Sergeant. Possibly one or two more in the crater zones where I can’t identify remains.”

McKenzie continued staring at the destruction. “In 19 seconds?” “Yes, Sergeant.” The sergeant turned to look at Reeves. “I called your trap stupid.” “Yes, Sergeant. You did.” “I was wrong. That wasn’t stupid. That was the most effective defensive system I’ve ever seen.”

Word of the trap’s success spread through the American defensive perimeter within hours. Officers from other companies came to examine the kill zone, trying to understand how one corporal with 57 grenades had eliminated an entire German infiltration element without firing a single shot. Lieutenant Walsh, who had questioned the trap’s value, conducted a detailed inspection of the trigger mechanisms and found everything exactly as Reeves had described.

A Lasting Impact

The after-action report filed later that day stated, “Corporal Reeves has demonstrated advanced understanding of mechanical engineering principles applied to defensive tactics. His integrated grenade system achieved casualty-to-munition ratio exceeding conventional employment by a factor of four. Recommend immediate documentation and dissemination of design principles.”

The psychological impact of Reeves’s trap was equally significant. The 26th Volksgrenadier Division, which had launched the infiltration attempt, immediately halted further attacks through the southern perimeter. German intelligence assessed the incident as an American minefield with delayed triggers, leading to a growing reluctance among their soldiers to conduct infiltration operations against American positions.

On December 23rd, as the weather cleared enough for air supply drops to reach Bastogne, Colonel Steve Chappies, commanding officer of the 52nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, personally delivered a case of grenades to Reeves’s position. “Corporal Reeves, I understand you can make better use of these than most men. How many more of your traps can you build?”

Reeves examined the grenades, noting that with this many, he could build three more systems covering their most vulnerable approaches. “Each system would require approximately two days to construct and test,” he replied. “You have four days until I expect the Germans to attack again. Build as many as you can. And Corporal, I’m assigning you three assistants. Teach them how your system works.”

The soldiers assigned to help Reeves were the same men who had mocked his first trap. Private Morrison, eager to learn, was the first to volunteer. “I was wrong about the trap. I want to make sure I’m not wrong about anything else.”

More Successes

Over the next four days, Reeves constructed two additional trap systems and partially completed a third. He taught his assistants the principles of redundancy, overlapping kill zones, sequential triggering, and failure compensation. The soldiers who had ridiculed him just days earlier now listened with complete attention to every detail.

On December 26th, German forces launched a major assault on Bastogne’s western perimeter, concentrating their attack precisely where Reeves’s second trap was positioned. As 29 German soldiers advanced in the pre-dawn darkness, they triggered the trap, resulting in a devastating cascade of explosions that killed all 29 men in just 23 seconds.

The third trap was triggered on December 28th by a German patrol attempting night infiltration on the northern perimeter. This time, 18 German soldiers died in 17 seconds. The psychological impact of these traps was profound, as German soldiers began to fear the American defenses, believing they had encountered advanced defensive technologies.

Legacy of Innovation

Daniel Reeves continued to serve through the end of the war, participating in Operation Market Garden and the final advance into Germany. He was promoted to sergeant and later to staff sergeant, recognized for his exceptional technical aptitude and ability to apply engineering principles to tactical problems.

After the war, Reeves returned to Penn State, completed his engineering degree, and spent 37 years at DuPont designing safety systems for chemical plants. His legacy lived on through the principles he demonstrated at Bastogne, which influenced military tactics for decades.

In interviews, Reeves often reflected on his experiences, emphasizing the importance of designing for failure and thinking systematically. His insights extended beyond military tactics, shaping principles in various fields, including industrial safety systems and modern engineering.

The story of Daniel Reeves and his ingenious grenade trap serves as a powerful reminder that innovation often arises from the courage to defy conventional wisdom. What was initially mocked as a “stupid trap” became a lifeline for American forces at Bastogne, proving that sometimes the most brilliant ideas are the ones that sound the craziest until they work perfectly.