This 17 Year Old Lied to Join the Navy — And Accidentally Cracked an Unbreakable Code

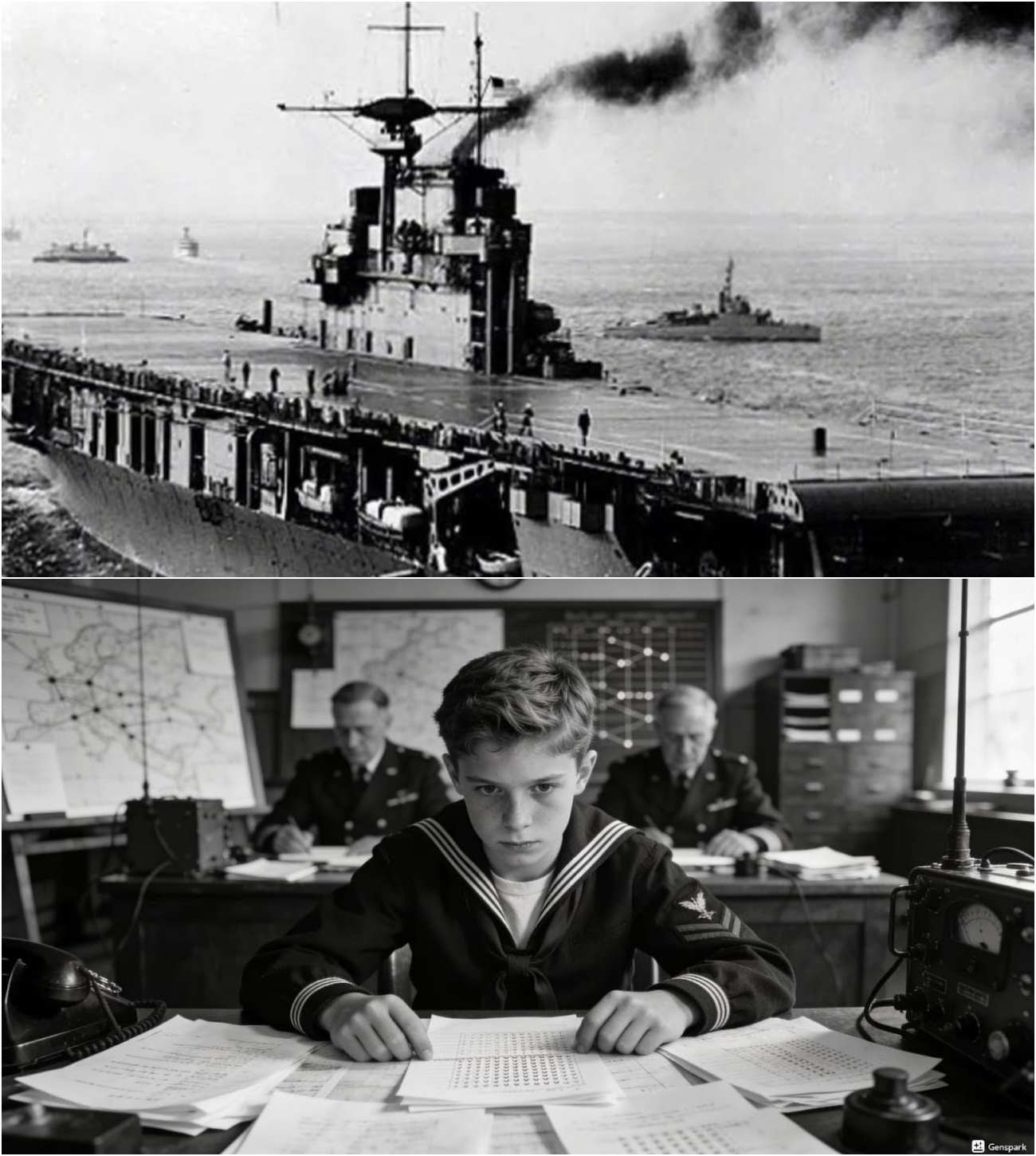

In the midst of the chaos that followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, when America was reeling from its first major defeat in the Pacific, the war in the Pacific seemed like an impossible battle. The Japanese forces, led by an unparalleled intelligence network, were outsmarting the United States at every turn. But amid this desperate struggle, an unexpected breakthrough was about to occur—not in a top-secret research lab, nor from a team of seasoned mathematicians or cryptographers, but from a teenage boy who wasn’t even supposed to be there.

The story begins in the sweat-filled basement of Building One at Pearl Harbor, on April 18th, 1942. It’s a humid morning, and Commander Joseph Rofort paces between rows of exhausted Navy crypt analysts hunched over piles of intercepted messages. The war was not going well. Japan had already overtaken vast swaths of the Pacific, including Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines. Despite the best efforts of American cryptographers, they were unable to break the Japanese naval code, JN25, which had remained impenetrable for over a year.

The Impossibility of JN25

The Japanese code was considered one of the most advanced and sophisticated cipher systems ever devised. It operated in two brutal stages: first, messages were encoded using a massive codebook containing 33 five-digit code groups. A single code group could represent a word, ship name, location, or command. Even if American cryptographers intercepted a message, they were staring at a string of numbers that had no meaning without the codebook.

But the Japanese didn’t stop there. They introduced a second layer of encryption, known as additive encryption. Before transmission, operators would add random five-digit numbers from separate additive tables to each code group, making the code even more complex. To make matters worse, these additive tables changed frequently—sometimes every few days.

With each passing day, the gap between what the Navy could decipher and what they needed to know widened. The Japanese were on the offensive, and every moment that passed without a breakthrough made it more likely that the war would slip out of America’s grasp.

Desperation Sets In

By early 1942, the Navy’s crypt analysts had barely broken through 1% of the JN25 traffic. Their methods, including frequency analysis and statistical attacks, had failed. The encryption seemed random, and the additive tables scrambled everything, making it appear as if the code was virtually unbreakable. Admiral Ernest King, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, was growing impatient. The Americans were blind to Japanese movements, and it was costing them dearly in lives and ships.

At this point, even the most brilliant minds in cryptography were giving up. The solution seemed out of reach. Mathematicians from prestigious institutions such as Yale and Princeton worked endless shifts, but nothing worked. Breaking JN25 was mathematically impossible, and with that realization, morale sank lower and lower. It was only a matter of time before Japan would strike again, and the U.S. Navy was powerless to stop it.

Enter Andrew Gleason

But into this atmosphere of defeat and frustration walked a 17-year-old named Andrew Mate Gleason. A teenager with no formal training in cryptography, no advanced education in mathematics, and no reason to be working in the Navy’s crypt analysis department at all. But Andrew had a gift—he could see patterns in chaos. While others looked at the strings of five-digit numbers and saw nothing, Andrew saw order where there should have been randomness.

Andrew, a kid from Fresno, California, had joined the Navy under false pretenses. Using a forged birth certificate, he had convinced a recruiter he was 19, even though he was actually 17. His voice hadn’t fully dropped yet, and his face was still baby-smooth, but his mind was sharp, and he had a peculiar talent: He could recognize patterns in seemingly meaningless data. After finishing high school early, he had spent a year working odd jobs, but nothing felt as important as the war. When the attack on Pearl Harbor happened, Andrew was determined to help.

He wasn’t recruited for his cryptography skills—he was recruited because he had listed an interest in math and puzzles on his intake form. By January 1942, Andrew found himself assigned to OP20G, the Navy’s crypt analysis division. He spent his days sorting intercepted Japanese messages, a task that felt far beneath him. But Andrew was restless, and the long hours gave him plenty of time to think. He couldn’t help but notice things—small inconsistencies, patterns that others had missed.

The Breakthrough

For weeks, Andrew sorted messages without being allowed to participate in the actual codebreaking efforts. But while others toiled over their desks, Andrew’s mind raced. Every time he handled a message, he thought about how it worked. One night, in the crypt analysis room, he spread out dozens of intercepted messages on his desk. They were all from the same Japanese transmission station, sent over a period of several months. Normally, the additive encryption would have rendered these messages meaningless, but Andrew noticed something strange.

There was a pattern in the header of each message. Japanese messages from Tokyo to Berlin only used the first 13 letters of the alphabet, while messages from Berlin to Tokyo used the last 13. It was a small detail, but it was enough to get Andrew thinking. What if the unencrypted indicators—the metadata at the start of each transmission—followed the same pattern? What if, by knowing the plain text structure of the indicators, he could subtract it from the encrypted message and reveal part of the additive table?

It seemed crazy. But Andrew tested his hypothesis. With nothing but pencil and paper, he cracked the code. And to his astonishment, it worked. He had uncovered a way to break through the additive encryption with 73% accuracy.

The Fight for Recognition

Andrew knew he had found something important, but he was just a teenager. No one in the Navy took him seriously. He tried to report his discovery to his superiors, but they were dismissive. “You’re here to file papers, not to play codebreaker,” one of the senior officers told him. But Andrew persisted. For three weeks, he refined his method in secret, increasing his accuracy to 81%.

Then, on May 11th, 1942, everything changed. The Navy was in crisis mode. Japanese radio traffic had exploded, and intelligence officers were scrambling to understand it. They knew something big was coming but couldn’t pinpoint where. The code, JN25, remained almost completely opaque. In the tense atmosphere of the briefing room, with Admiral Nimitz looking on, Andrew stood up.

“I think I know how to break the additives,” he said. The room fell silent. No one had asked for the opinion of a 17-year-old message sorter, but Andrew had the courage to speak up.

“I’ve been testing a method,” he continued, “and it works. The indicator headers in Tokyo-Berlin traffic use split alphabets. A through M one direction, N through Z the other. If we assume plain text follows the same pattern, we can recover additive tables by subtraction.”

To his amazement, the room began to listen. Senior cryptographers and mathematicians, including Agnes Driscoll and Marshall Hall Jr., began testing his method. Within hours, they confirmed it worked. The breakthrough was undeniable.

The Battle of Midway

Thanks to Andrew’s method, the Navy began to crack JN25 at a previously unimaginable rate. Within days, they identified the location of the Japanese fleet—Midway Island. This intelligence allowed Admiral Nimitz to plan a decisive ambush. On June 4th, 1942, American dive bombers destroyed three Japanese carriers—Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu—in just five minutes, a blow that turned the tide of the Pacific War.

The success at Midway was a pivotal moment in World War II. It crippled Japan’s carrier fleet and forced them onto the defensive. But it also had a deeper significance. It was made possible by a 17-year-old who shouldn’t have been there, who wasn’t supposed to know the answer, but who saw something others had missed.

The Legacy of Andrew Gleason

Andrew’s work didn’t end with Midway. His method was refined and developed into a comprehensive system for breaking JN25. By the end of 1942, the Navy was reading 75% of the Japanese traffic, saving thousands of American lives and changing the course of the war.

After the war, Andrew Gleason went on to become one of the most respected mathematicians of his generation. He solved Hilbert’s fifth problem, revolutionized quantum mechanics, and became a professor at Harvard. But he never talked about his role in breaking the Japanese naval code. It wasn’t until years later, when the records were declassified, that the world learned the truth.

Andrew Gleason, the teenage codebreaker, proved that sometimes, the most impossible problems can be solved by someone who doesn’t know they’re not supposed to be able to solve them. His discovery didn’t just help win the Battle of Midway—it helped win the war in the Pacific.

In a rare interview, Gleason said, “I was young and stupid and lucky. The real heroes were the people like Rofort and Driscoll who’d been fighting that code for years. I just noticed something they’d been too busy to see. If anything, it proves that sometimes you need fresh eyes on a problem.”

Andrew Gleason may have been young, but his breakthrough changed history. The world would never forget the kid who cracked an unbreakable code and helped save the Pacific Fleet.