What Eisenhower Said When Patton Asked: “Do You Want Me to Give It Back.

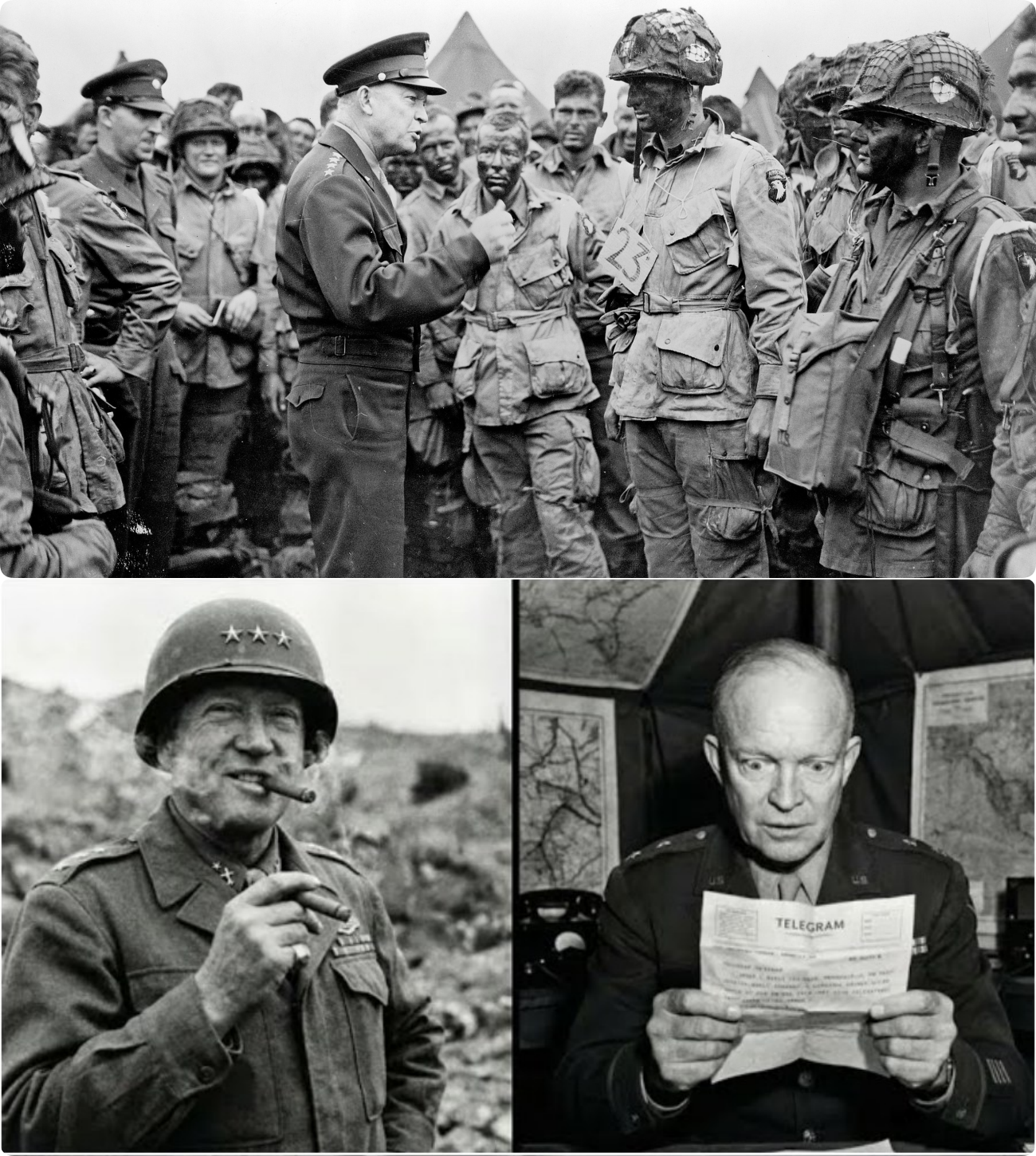

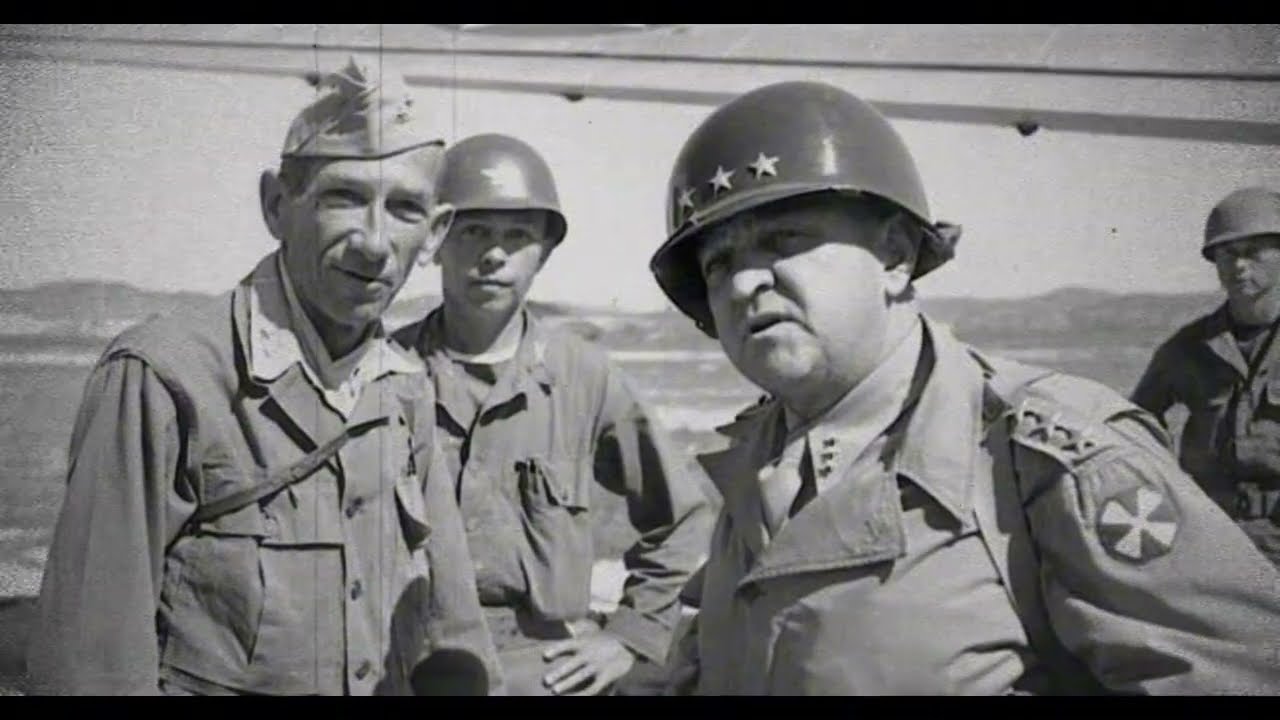

March 2nd, 1945, a message arrived at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. The headquarters was located in Paris, far away from the mud and blood of the front lines. The message was addressed to the Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. It came from the commander of the Third Army, General George S. Patton. Usually messages between generals are formal. They are cold. They are professional. They talk about supply lines. They talk about casualties. They talk about coordinates.

But this message was different. It was short. It was sharp. And it dripped with a sarcasm so heavy it could have cracked the telegraph wires. The message read, “Have taken trier with two divisions. Do you want me to give it back?” When the staff officers at headquarters read it, they stopped. Some of them gasped. Some of them laughed nervously because they knew the context. Just hours earlier, headquarters had sent an urgent order to Patton. The order was clear.

Do not attack Trier. Bypass it. It is too strong. You need four divisions to take it. Eisenhower was telling Patton to stop. But by the time the order arrived, Patton had already won. He had taken Germany’s oldest city. He had defied the laws of military strategy. And now he was taunting his boss. This is the story of that telegram. But more importantly, this is the story of the impossible battle that led to it. How Patton broke through the Sigf freed line, how he crossed a river of fire, and how he proved once again that while other generals fought with maps, he fought with instinct.

To understand why taking tri was impossible, we have to look at where the Third Army was standing in February 1945. Cracking the Siegfried Line They were facing the west wall. The allies called it the Seief freed line. It was the most formidable defensive network ever built by human hands. Hitler had constructed it to protect the fatherland. It wasn’t just a trench. It was a zone of death. Miles deep, filled with concrete bunkers, hidden artillery, minefields, and dragon’s teeth.

rows of concrete pyramids designed to stop tanks dead in their tracks. The weather was brutal. The ground was a soup of freezing mud. Tanks sank up to their axles. Trucks stalled. Soldiers suffered from trenchfoot. Most generals looked at the Seagreed line and paused. They wanted to wait for air support. They wanted to stockpile millions of shells. They wanted to be safe. But Patton didn’t do safe. He knew something about the German army that the other generals ignored.

He knew they were breaking. He knew that a defensive line is only as strong as the men inside it. And the Germans were tired. Patton called his core commander, General Walton Walker. Walker was a short, angry, aggressive man. Patton loved him. He called him his bulldog. Patton pointed to the map. He pointed to the triangle between the Sar River and the Moselle River. At the tip of that triangle sat the city of Trier. Trier was a prize.

It was the oldest city in Germany, founded by the Romans 2,000 years ago. It was a symbol of German history and it was a vital road junction for the supply lines heading to the Rine. Patton told Walker, “I want you to punch a hole in that line, and I want you to go for Trier.” Walker looked at the map. The terrain was a nightmare. Steep hills, dense forests, concrete pillboxes covering every road. But Walker was Patton’s man.

He didn’t ask if, he asked when. To crack the Sief Freed line, Patton committed his best unit, the 10th Armored Division. They were known as the Tiger Division. On February 19th, the attack began. It was not a subtle maneuver. It was a sledgehammer. The American tanks roared forward. They smashed into the Dragon’s teeth. Combat engineers ran forward under heavy machine gun fire to blow gaps in the concrete obstacles. It was slow. It was bloody. German artillery rained down from the hills.

The 94th Infantry Division fighting alongside the tanks cleared the pillboxes one by one. They had to throw grenades into the firing slits. They had to use flamethrowers to burn the defenders out. For three days, it looked like a stalemate. The mud was winning. The “Impossible” Odds: 2 Divisions vs 4 American tanks were sliding off the roads. At Supreme Headquarters in Paris, the mood was anxious. Eisenhower’s staff watched the progress on the map. They saw the Third Army moving inches at a time.

They worried that Patton was getting bogged down. They worried about casualties. They began to draft plans to halt the operation. They wanted to shift resources to Montgomery in the north. Montgomery was preparing for his own massive crossing of the Rine, and as always, he demanded all the supplies. If Patton stalled, Eisenhower would take his fuel and give it to Monty. Patton knew this. He felt the clock ticking. He wasn’t just fighting the Germans. He was fighting the politics of the Allied command.

He drove to the front. He stood in the mud, yelling at the tank commanders, “Keep moving. If you stop, you die. Keep moving.” And then the line cracked. On February 24th, the 10th Armored Division broke through the main belt of the Seagreed line. Suddenly, they were in the open. The German rear guard collapsed. The Tiger tanks began to run. They raced east toward the Sar River, toward Trier. By late February, Patton’s forces were closing in on the city, but the Germans were not giving up Trier easily.

The city was a natural fortress surrounded by hills protected by the Moselle River. The German high command ordered that Trier be held to the last man. They flooded the approaches to the city. They rigged the bridges with explosives. At Allied headquarters, the intelligence reports were grim. They estimated that Trier was defended by thousands of troops. They identified anti-tank guns hidden in the Roman ruins. The planners at SHA, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force did the math. To take a fortified city like Trier, urban combat house to house, street to street, military doctrine stated you needed a 3:1 advantage, ideally 4:1.

Patton only had two divisions in the area, the 10th armored and the 94th Infantry. He was outnumbered or at best evenly matched against a dugin enemy. The Night Attack on Trier Eisenhower’s operations officer advised him to intervene. Patton is walking into a trap. They said he will get stuck in a meat grinder in the city streets. He should bypass Trier, go around it, let the follow-up forces deal with it later. It was a sensible decision, a cautious decision.

Eisenhower agreed. A message was drafted. It was sent through the chain of command. Bypass Trier. Do not engage. Wait for reinforcements. But messages in 1945 didn’t travel instantly. They had to be decoded. They had to be typed. They had to be driven by motorcycle couriers to the front. And while that message was making its slow journey from Paris to the front, Patton was already moving. He had sensed the hesitation from above. He knew an order to stop was likely coming.

So he decided to make the issue moot. He decided to present Eisenhower with a fetak plea, a done deal. He called General Walker. “Take Trier,” he said, “and do it tonight.” The night of March 1st. The 10th Armored Division was perched on the hills overlooking Trier. Below them, the ancient city lay in darkness. The commander of the attack faced a dilemma. There was only one way into the city for his tanks, the bridges. The Moselle River cut the city off.

If the Germans blew the bridges, the tanks would be stuck on the wrong side. The infantry would be slaughtered trying to cross in rubber boats. There were two main bridges, the Kaiser Brooka and the Ror Ba, the Roman bridge. a marvel of engineering. Built by the Roman Empire in 16 BC, it had stood for nearly 2,000 years. Legions had marched across it. Knights had ridden across it. Napoleon had crossed it. And now, American Sherman tanks were coming for it.

But the Germans knew its value. They had packed the stone arches with tons of dynamite. A German officer stood ready with the detonator. The American plan was simple and incredibly dangerous. Rush the city in the dark. Use speed to shock the defenders and capture the bridge before they could push the plunger. Lieutenant Colonel Jack Richardson led the charge. At 0200 hours, the American engines roared to life. They didn’t use artillery preparation. That would have warned the Germans.

They just charged. The tanks smashed through the roadblocks on the outskirts. They raced down the winding roads into the valley. German sentries fired flares. Suddenly, the night was lit up. Machine gun fire erupted from the windows of the houses. Panzer Fost rockets stre through the air. The lead American tank took a hit. It Saving the Roman Bridge (Action) burst into flames. But the column didn’t stop. They pushed the burning tank off the road and kept going. They reached the first bridge, the Kaiser Brooka.

Just as the lead tank approached it. Boom! A massive explosion ripped through the night. The bridge collapsed into the river. The Germans had blown it. That left only one chance, the Roman bridge. Richardson ordered his men to drive like maniacs. Get to that bridge. They navigated the confusing narrow medieval streets. Maps were useless in the dark. They followed the river. They turned a corner. And there it was, the Roman bridge, intact. But the approach was covered by machine gun nests.

and they knew the explosives were primed. This was the moment that would decide the battle. If the bridge blew, Patton’s gamble would fail. He would be left with two divisions stuck on the wrong side of the river. Eisenhower’s warning would be proven right. A platoon of infantry led by a young lieutenant jumped off the backs of the tanks. They sprinted toward the bridge. Bullets sparked off the ancient stones. Men fell, but they kept running. They reached the middle of the bridge.

It was an eerie feeling. Every step, they expected the ground to open up beneath them. They expected to be vaporized, but the explosion never came. Maybe the German commander hesitated. Maybe a stray bullet cut the wire. Maybe the detonator malfunctioned. Or maybe the speed of the American attack was just too fast. The Germans were so shocked to see enemy soldiers on the bridge that they panicked. The Americans reached the far side. They found the wires leading to the demolition charges.

They cut them. They bayonetted the defenders in the bridge house. They fired a flare. The signal was green. The bridge was secure. Within minutes, the heavy Sherman tanks of the 10th Armored were rumbling across the Roman stones. The sound must have been terrifying for the German defenders. The roar of engines echoing off the valley walls. Do You Want Me to Give It Back? Once the tanks were inside the city proper, the defense collapsed. The Germans surrendered in droves.

By dawn on March 2nd, Trier was secure. The American flag was raised over the Port of Negra, the ancient Roman gate. It was a master stroke. Patton had captured a fortress city. He had secured a crossing over the Moselle, and he had done it with minimal casualties. He had done with two divisions, what Schae said would require four. Later that morning, George Patton stood in his headquarters. He was in a good mood. He was smoking a cigar.

He was listening to the reports coming in from Trier. Then an aid walked in. He looked nervous. He held a piece of paper in his hand. General, the aid said, a message from Supreme Headquarters from General Eisenhower. Patton took the paper. He read it. It was the order, the order that had been drafted the day before. Bypass trier. It will take four divisions to capture it. Patton read it again. He started to chuckle. Then he started to laugh, a loud, booming laugh.

The irony was perfect. The bureaucracy was so slow and his army was so fast that the orders were obsolete before they even arrived. He looked at his staff. “They think we can’t do it,” Patton said. “They think we need four divisions.” He sat down at his desk. He took a pencil. He could have just sent a standard reply. Mission accomplished. Trier secured. That would have been the professional thing to do. But Patton was still stinging from the lack of trust.

He was annoyed that Eisenhower always prioritized Montgomery. He wanted to rub it in. He wanted to make sure they understood exactly how wrong they were. He wrote the famous words, “Have taken trier with two divisions.” And then the Eisenhower’s Reaction punchline. Do you want me to give it back? He handed it to the radio operator. Send it, he said. Send it directly to Ike. When the message arrived at Versailles, it caused a stir. Eisenhower was a serious man.

He carried the weight of the world on his shoulders. But when he read Patton’s telegram, even he couldn’t help but smile. It was classic Patton. Arrogant, insubordinate, but undeniably brilliant. Eisenhower knew he couldn’t punish Patton. You don’t punish a general for winning a major victory ahead of schedule and under budget. The capture of Trier opened the gateway to the Rine. It accelerated the end of the war by weeks. Eisenhower reportedly folded the telegram and put it in his pocket.

He didn’t reply to the sarcastic question. He simply issued a new order. Congratulations. Keep moving. But the message sent a shockwave through the Allied command. It silenced the critics. It proved that the patent method, speed, violence, and ignoring the rule book worked better than the cautious, methodical approach favored by the British. For the soldiers of the Third Army, the story of the telegram became a legend. It was whispered in the mesh halls. It was shared in the foxholes.

Did you hear what the old man told Ike? It gave them pride. It made them feel like they were part of an outlaw army. An army that could do the impossible. The capture of Trier is often overshadowed by bigger battles. the battle of the bulge, the crossing of the rine. But in many ways, it is the perfect example of George S. Patton’s genius. He understood that in war, time is the only currency that matters. Waiting for four divisions would have given the Germans time to reinforce.

It would have turned Trier into a Stalenrad. By attacking now with less, he achieved more. And that telegram, do you want me to give it back? It remains one of the greatest lines in military history. It was a reminder to the politicians and the planners that while they were debating what was possible, the warriors were already getting it done. Patton didn’t just capture a city that day. He captured the essence of victory.