Why Patton Never Came Home

December 21st, 1945. 6 in the evening. H Highidleberg Army Hospital. Doctors are rushing through the corridors. Nurses are shouting orders. The heart monitor is screaming its alarm. A man lies in the bed, paralyzed from the neck down. For 12 days, he has not moved. For 12 days, he has been fighting death.

But this time, he is losing. A blood clot travels through his paralyzed body. It reaches his heart and it stops. George S. Patton, 60 years old, dead. The man who made Europe tremble. The commander who haunted Hitler’s nightmares. History’s most ruthless general. He is dying from a car accident. Not on the battlefield. Not heroically. Not from enemy bullets.

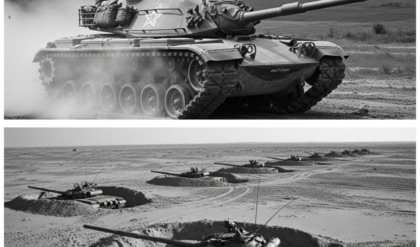

Just an accident. Just a truck. Just a broken neck. 12 days earlier on December 9th, Patton was sitting in the back seat of his 1938 Cadillac staff car. His driver, Private Firstclass Horus Woodring, was taking him on a pheasant hunting trip near Mannheim, Germany. The war was over.

The danger was supposed to be gone. At a railroad crossing, a 2 and a half ton army truck suddenly turned left in front of them. Wooding hit the brakes, but could not stop in time. The collision was not even that violent. The truck driver walked away without a scratch. Wooding was uninjured. Major General Hobart Gay, sitting next to Patton, had only minor bruises, but Patton was thrown forward.

His head struck the partition between the front and back seats. His neck snapped. In an instant, the most feared commander in the Allied forces was paralyzed from the neck down. He knew immediately what had happened. He looked at Gay and said calmly, “I think I am paralyzed. Rub my fingers.” There was no feeling.

For 12 days, the doctors tried everything. They put him in traction. They brought specialists from England and America. His wife Beatrice flew across the Atlantic to be by his side. The whole world was watching. Newspapers printed daily updates. Soldiers prayed for their general. But the body that had survived two world wars, countless battles, and enemy fire could not survive a blood clot.

At 6:00 in the evening on December 21st, George S. Patton took his last breath. And then came the question that would shock America. Where do you bury the most famous general in the country?

The answer seemed obvious. Arlington National Cemetery, a state funeral in Washington. President Truman would speak, generals would salute, the nation would mourn.

That is what you do for a hero. But then Beatatrice Patton made a phone call and she said one sentence that changed everything. George is not coming back to America. The war department was stunned. What do you mean not coming back? This is the nation’s greatest general, the conqueror of Europe, the man who saved Bastonia.

How can he stay overseas? But Beatatrice had a letter written in George’s own handwriting, dated July 1943, just before the invasion of Sicily, the night before he might have died. In that letter George had written his final wish. If I should conchk, I do not wish to be disinterred after the war. It would be far more pleasant to my ghostly future to lie among my soldiers than to rest in the sanctimonious precincts of a civilian cemetery.

the world’s toughest general had made his choice. Even in death, he wanted to be with his men. Beatrice was given three options for burial locations. She chose without hesitation. The Luxembourg American cemetery at Ham. It was where the Third Army had lost most of its men. It was where Patton had fought his hardest battle.

It was where his soldiers were waiting for him. On December 22nd, Patton’s body was brought to Va Reneier in H Highleberg. He lay in state so soldiers and civilians could pay their final respects. Lines stretched around the block. Men who had fought under him wept openly. German civilians who had feared him now stood in silence with bowed heads.

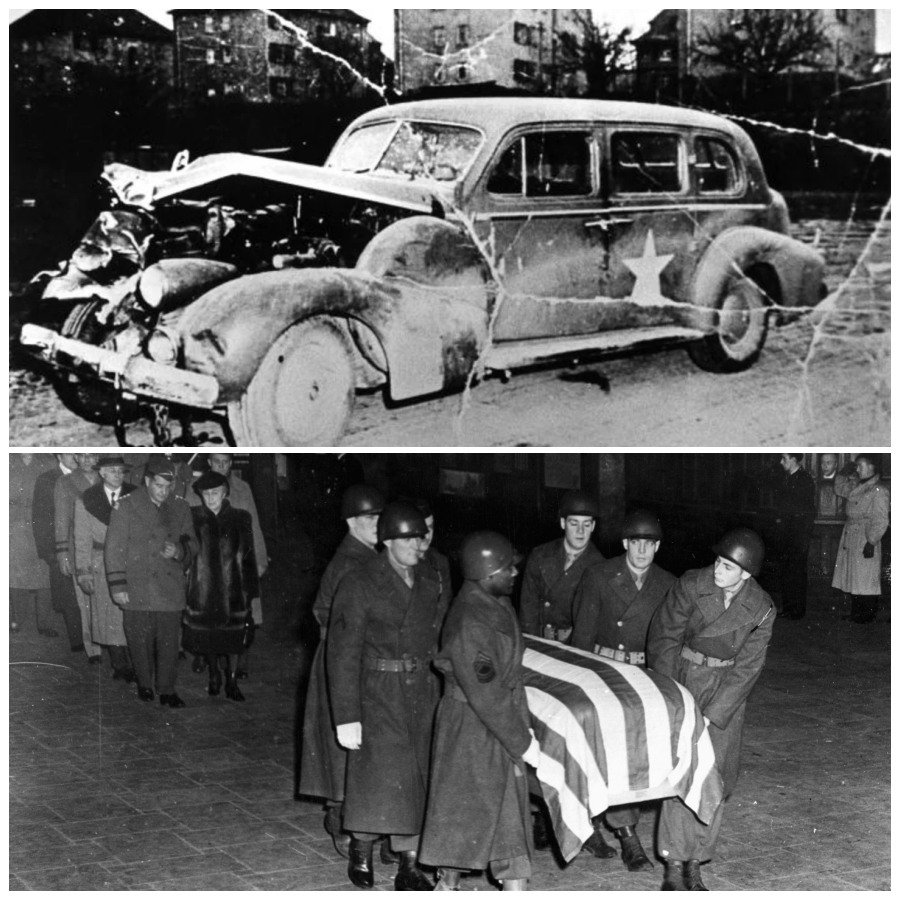

The next day, December 23rd, the funeral procession wound through the streets of H Highleberg. People lined the sidewalks. Some climbed onto rooftops just to catch a glimpse. Cavalry reconnaissance vehicles led the way. Behind them came an M3 halftrack bearing patterns flag draped gunmetal casket. Helmeted soldiers in white gloves marched alongside.

The procession stopped at Christ Episcopal Church for the funeral service. Then the casket was placed aboard a special funeral train for the 240 m journey to Luxembourg. The train traveled through the night. At every stop, soldiers gathered on the platforms to salute. And at every stop, no matter the hour, Beatatrice stepped out onto the platform and made a short speech in French, thanking the troopsfor their tribute to George.

Her brother Frederick Ay watched in amazement at her strength. 13 hours she rode that train. 13 hours she honored her husband. December 24th, 1945. Christmas Eve. The train arrives in Luxembourg. A light rain is falling. Gray skies hang over the city. But the streets are not empty. Thousands of people are waiting.

Luxembourers who remember liberation. Soldiers who remember their commander. Locals remove their hats as the casket passes. Representatives from nine countries have come to pay respects. France, Belgium, England, Italy, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Luxembourg. The highest ranking officers of American forces in Europe stand at attention.

France and Belgium provide the honor guard. A French battery fires 17 rounds of salute. The sound echoes across the city. A riderless horse joins the procession, boots reversed in the stirrups, the ancient symbol of a fallen warrior. In the gray skies above, an aircraft circles desperately. Lieutenant General Walton Walker, one of Patton’s most trusted core commanders, is trying to land.

He wants to be there for his general, but the cloud cover is too low. He cannot make it down. He can only watch from above as his commander makes his final march. The procession moves past the Luxembourg Royal Castle, past the cathedral, out to the cemetery at Ham. Here 5,76 American soldiers already rest. Men of the Third Army, men who died in the Arden, men who followed Patton into hell and never came back.

The grave has been dug by German prisoners of war. There is a bitter irony in this. The enemy he defeated is now preparing his final resting place. Under a large tent to shield mourers from the rain, the pawbearers place Patton’s casket over the open grave. Master Sergeant William Meeks, Patton’s personal orderly for many years, is one of them. His hands are shaking.

His eyes are wet. Beside the masked colors, Beatatrice stands with perfect composure. She has not broken down. She will not break down. Not here. Not in front of George’s soldiers. Next to her stands General Joseph Mcnani, the theater commander, and General Lucien Truscott, the new Third Army commander.

Dignitaries from nine nations bow their heads. The rain drifts down and the chaplain reads the burial service. There are no long speeches, no political statements, just the ancient words of faith and farewell. Then the honor guard raises rifles. Three volleys crack through the wet air. A bugler plays taps. The notes float across the rows of white crosses.

Across the graves of 5,000 soldiers across the fields where blood was spilled just one year ago, and George S. Patton is lowered into the ground. He is buried in plot B, row 12, grave 24, right in the middle of his men, exactly as he wanted. Not at the front, not in a place of honor, just another soldier among soldiers.

But Patton could not stay anonymous even in death. In the months and years that followed, visitors began pouring into the cemetery. So many visitors that they were damaging the grounds around his grave. People were trampling over other soldiers graves just to reach Patton. In 1947, the graves registration service made a difficult decision.

They moved Patton’s remains to the front of the cemetery. Plot P, row one, grave one. Now he stands at the head of his troops, forever facing east, forever watching over them. Beatrice reluctantly agreed to the move. She understood the necessity, but she made them promise it would be the final move. She wrote that George was not moved because of his rank.

He was moved to protect the other graves from damage. Even in death, he was still protecting his men. Beatatrice visited the grave as often as she could. She never remarried. She devoted herself to preserving George’s memory. On September 30th, 1953, 8 years after her husband’s death, Beatatrice Patton died. She was cremated and a portion of her ashes was scattered on George’s grave.

They are together now in that cemetery in Luxembourg, far from California where they fell in love. Far from America where they built a family, but close to the soldiers George loved more than anything else. Today, the Luxembourg American Cemetery is one of the most visited American military cemeteries in Europe. Every year, thousands come to pay respects.

They walk past the white marble chapel with its stained glass windows. They walk past the reflecting pool. They walk past row after row of white crosses and stars of David. And they stop at plot P, row one, grave one. A simple white cross marks the spot. George S. Patton Jutter, General Third Army, California, December 21st, 1945.

Nothing about his victories. Nothing about Bastonia or Sicily or the Rine. Just his name, his rank, his home, and the date he died. But everyone who stands there knows the rest. They know about the tanks that rolled across Africa. They know about the army that pivoted north in 48 hours. They know about the general who made theimpossible possible.

And they know about a letter written on a night before battle. A letter that said he wanted to lie among his soldiers. It would be far more pleasant to my ghostly future to lie among my soldiers than to rest in the sanctimonious precincts of a civilian cemetery. He got his wish. The most famous general of World War II is not buried in Arlington.

He is not buried in Washington. He is not buried in some grand monument surrounded by politicians. He is buried in a field in Luxembourg with 5,076 of his men right where he belongs. 80 years later people still come. They leave flowers. They leave coins. They leave letters. Some are veterans. Some are children of veterans.

Some are just people who read about him in history books. But they all come for the same reason. to honor a general who even in death refused to leave his soldiers behind. That is the story of George S. Patton’s last journey. A man who lived for war died in peace. A man who terrified enemies was beloved by his men. A man who could have been buried anywhere chose to rest with the soldiers who followed him into hell.

Some generals seek glory. Some generals seek power. Patton sought only one thing, to be with his troops. And on Christmas Eve 1945, in a rainy cemetery in Luxembourg, he finally joined them forever.