“You Can Go for a Walk If You Want” — German POWs Were Shocked by America’s Fence Free Camps

“When the Enemy Became Human: How America’s Fence-Free POW Camps Destroyed Nazi Ideology”

In the sweltering heat of the Mississippi Delta, far from the battlefield where Nazi forces were waging war on the Allied powers, German prisoners of war faced an unimaginable reality in America’s POW camps. The place where they were expected to be humiliated, broken, and reprogrammed was surprisingly different. In the midst of the looming shadows of the war, this was where enemies not only survived—they thrived.

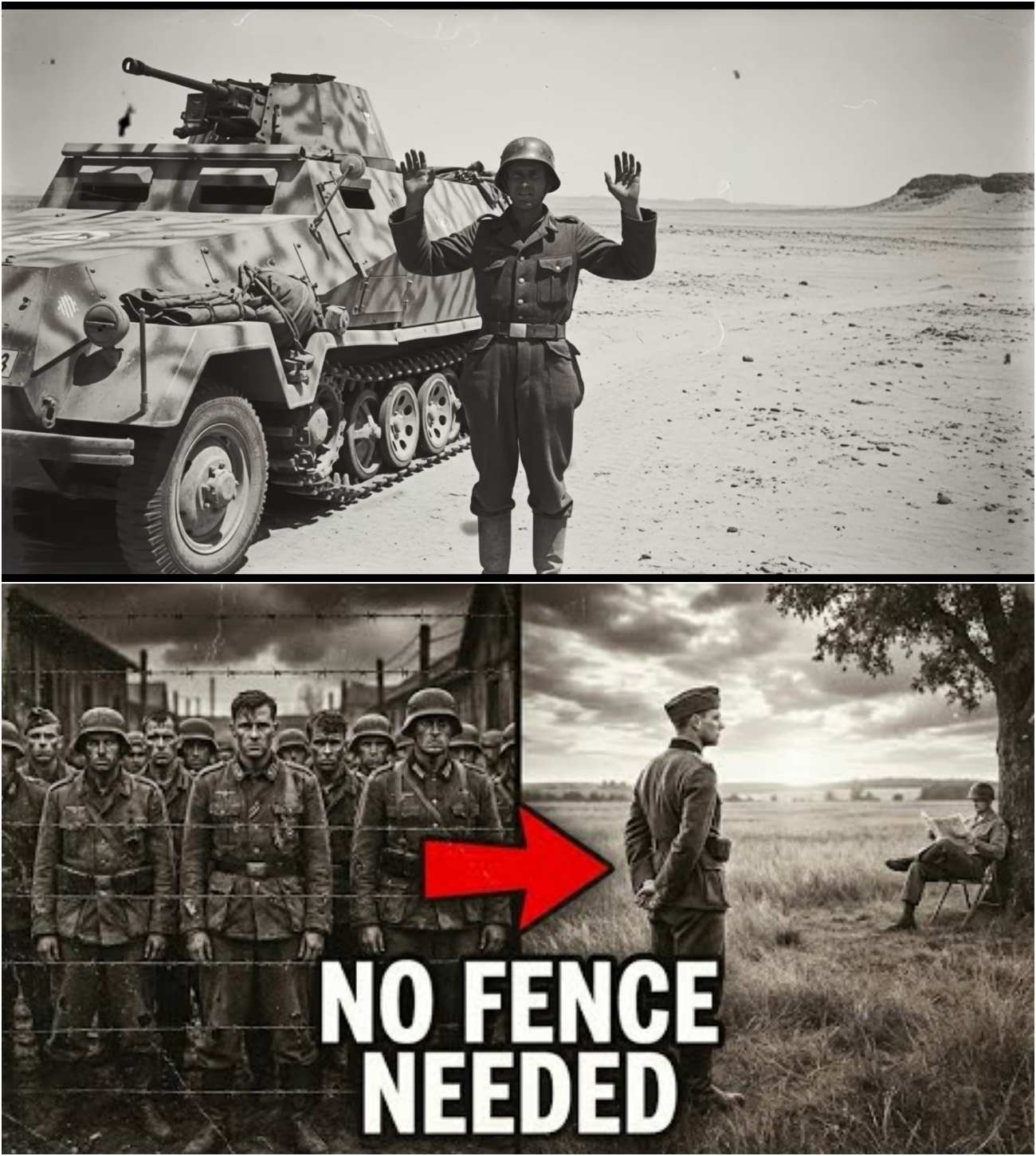

It was May 13th, 1943, when the world shifted for Ober Jeffraider Corporal Hans Muller. For months, Tunisia had been a hellscape of death and destruction, where Nazi forces, once invincible under the legendary Desert Fox Erwin Rommel, were broken. Hans, just 22 years old and a seasoned veteran of the Afrika Korps, had been taught to fear one thing: surrender. When the Allied forces swept in, he was told by his superiors, by German propaganda, that the Americans would execute prisoners. They were a chaotic, lawless people, they said, who would stop at nothing to destroy them. They were gangsters, cowboys without discipline, set to treat any German soldier with unspeakable brutality.

Hans had his rifle at the ready, awaiting the shot. He was prepared to die with the conviction that it would be a quick death, brought about by these ‘barbaric’ Americans. But instead, what he received was a gesture—a simple thumb pointing towards the road. “That way, Fritz,” the American GI had said, chewing gum nonchalantly as he slung his Thompson submachine gun. No bullet. No violence. Just a calm direction to walk. They were prisoners now, but not the way they had been taught to expect.

This was the first crack in the wall of lies that Nazi propaganda had built around their minds. The fear that had kept them fighting until their last bullet now had to contend with a very different reality. In the days that followed, Hans and thousands of his comrades were herded onto transport trucks, stripped of their weapons and medals, but not their dignity—at least not yet. Packed into the holds of Liberty ships bound for America, they soon realized that their greatest fear was not what awaited them in captivity, but what they left behind.

For the next two weeks, the prisoners sailed across the Atlantic, living in a bitter irony. They were soldiers who had once fought on the sea against Allied ships, and now, they found themselves praying that their own submarines wouldn’t sink the ship they were aboard. And still, it was not the enemy they feared. It was the silence that followed their arrival in America.

As the ship docked, the American lights shone across the city skyline. New York, like an arrogant giant untouched by the flames of war, glowed in the night. No blackout, no fear of air raids—just an overwhelming confidence that made Hans question everything he had been taught to believe about the enemy. These people weren’t afraid of war; they were beyond it.

Hans and the other prisoners were processed, fingerprinted, and issued numbers. The brutality they had been promised never came. The American guards were indifferent, firm but not cruel. And when they were loaded onto trains to be moved inland, Hans expected the cattle cars that had carried so many of his own soldiers. Instead, he walked into a Pullman coach—complete with cushioned seats and windows, a far cry from the squalid conditions they had endured in Europe.

The vast American countryside outside the train windows became a symbol of both awe and dread. In Europe, two days of travel meant crossing several borders. But here, two days of travel meant nothing more than crossing a single state. The scale of the land was incomprehensible. This was a country capable of producing war material on a scale far greater than Germany could ever hope to achieve. The realization was crushing. Hans wasn’t just fighting a war—he was fighting an entire continent, a machine too large to defeat.

When the prisoners arrived at Camp Aliceville in Mississippi, they braced themselves for the worst. The familiar sight of fences and guards should have been reassuring. Yet, it was not what they expected. The camp resembled a small town more than a prison. There were no dogs. No electrified fences. Just wooden barracks, rows of them, and the quiet hum of a camp where life, surprisingly, seemed to be normal.

What happened next was even more shocking. Hans, assigned to a work detail on a local cotton farm, expected to see an armed guard watching their every move. But instead, they were left alone. A single American soldier sat on the truck, reading a comic book while the prisoners worked the fields. This was the America they had been taught to fear. The place where men could be trusted to work for their food, where no bars or locks were necessary. Here, prisoners weren’t just fed; they were given trust, a dangerous commodity for men trained to fight and die for their country.

The realization hit Hans like a freight train. These men—the Americans—were not what they had been told. The rumors of brutality, of violence, were all lies. And yet, what did they have to lose? The vast American wilderness stretched before them, offering escape to anyone who dared to take it. But in that moment, when the wind rustled through the fields and the sun beat down on their backs, Hans understood the true nature of captivity. The fences were not made of wire—they were made of geography, of plenty, of a world so large that running away meant nothing. It meant nothing at all.

Even the farmer who owned the land, a man who had lost his own nephew in the war, did not treat them like enemies. At the end of the workweek, he invited the prisoners to dinner. Fried chicken, mashed potatoes, collard greens, and iced tea. The smell wafted through the air, intoxicating in its simplicity. And for the first time since their capture, the men realized that their enemies, the Americans, were human.

The realization that the enemy was not made of monsters was disorienting. For months, the Nazis had been taught to hate these people, to see them as faceless, barbaric opponents. And yet here they were, breaking bread together, laughing, talking. The bond they shared in that moment transcended the borders of nations, of ideologies, of histories written in blood.

But not all was peaceful. The ideological poison of the Third Reich remained alive in the hearts of many of the prisoners. In the shadows of the camp, the hardliners—SS men and fanatical soldiers—continued to spread their doctrine. The constant fear of betrayal was palpable. They controlled everything: the mail, the newspapers, the very conversations that took place under the flickering lights of the barracks.

And then, it happened. A young prisoner, Werner, was accused of treason. He had been friendly with the Americans. He had spoken to them, laughed with them. For this, he was judged guilty. The trial was swift, brutal, and final. His life was taken, not by the Americans, but by his own comrades. The camp was silent, the air heavy with the knowledge that even here, in this land of plenty, the ideological chains of the Nazis had not yet been broken.

But even in the face of such darkness, the walls of propaganda began to crumble. The Americans, realizing the true nature of the danger, took steps to break the Nazi grip on their prisoners. Through a program of “denazification,” they showed the prisoners the horrors their own government had inflicted on the world. It was a brutal awakening—one that would take time to sink in.

By the end of the war, the once-proud men of the German army had been reduced to prisoners, their world broken by the very enemy they had been taught to destroy. They returned to a shattered Germany, a nation that no longer existed. They carried with them memories of kindness, of food, of walks in the sunshine. And they carried with them the knowledge that they had been deceived—not just by the enemy, but by their own leaders.

As the years passed, many of these men returned to America, not as enemies, but as friends, seeking to understand the land that had once been their captor. Hans Muller, now an old man, returned to the farm in Mississippi where he had once harvested peanuts. The son of the farmer, now a man in his fifties, welcomed him as an old friend.

In the end, it was not the tanks or the guns that destroyed Nazi ideology. It was the simple, unyielding humanity of the Americans who treated their enemies with decency, even in the darkest of times. And in that moment, the line between enemy and ally was forever blurred.

The golden cage had rusted, but Hans Muller would never forget the moment when the enemy became human again.