“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

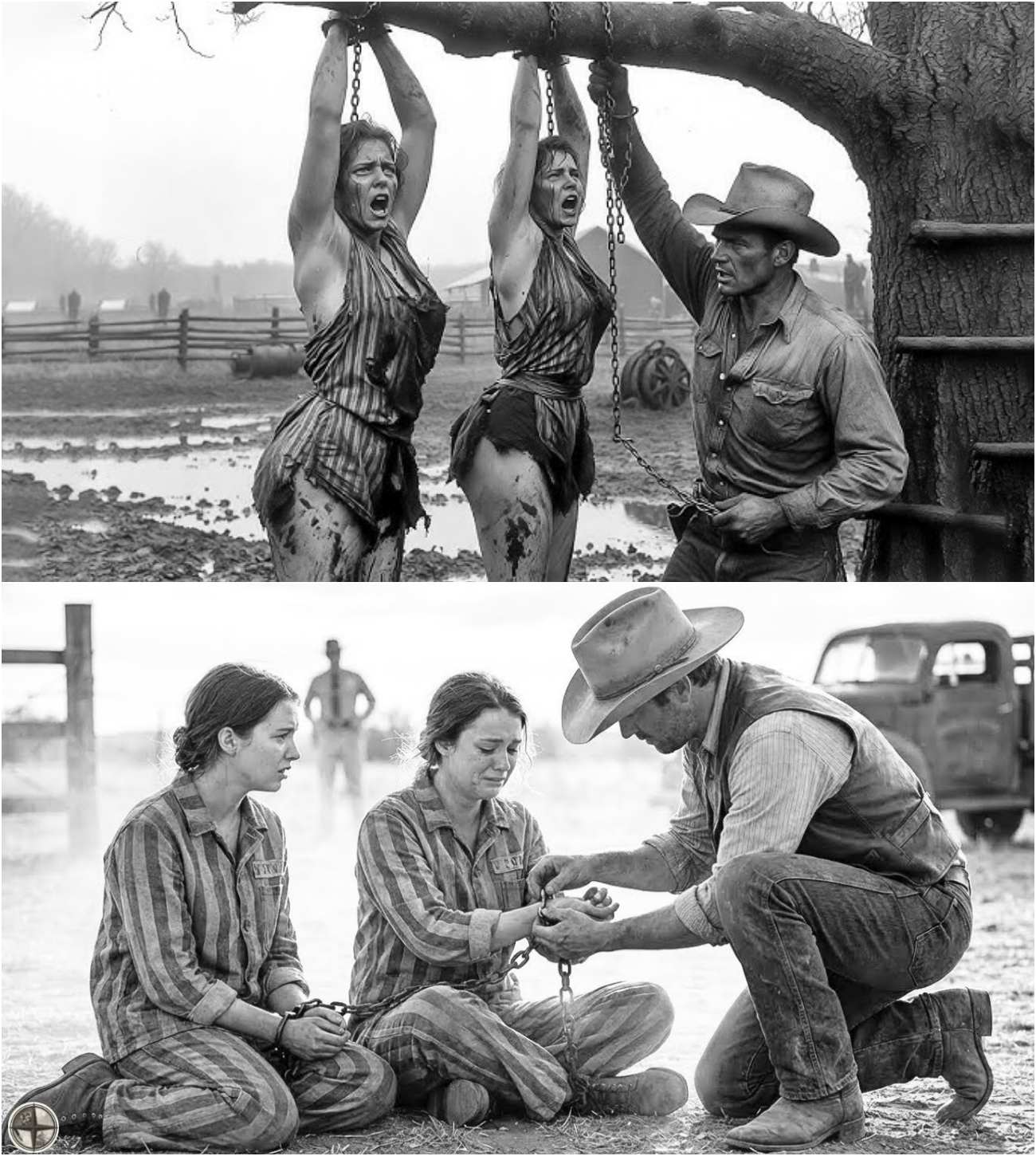

In the scorching heat of Texas in the summer of 1944, a group of German women stood shackled, their wrists raw and red from the metal chains that had bound them for three long weeks. They had been transported from war-torn Europe, expecting the worst. They had crossed an ocean, survived brutal conditions, and braced themselves for torture, starvation, and endless hardship. But what they found in the small Texas camp was something they had never anticipated—something that would challenge everything they had ever believed about their enemies, and even about themselves.

The women, captured as part of the German Women’s Auxiliary Corps, had been tasked with supporting the war effort in ways that didn’t require pulling triggers. Nurses, clerks, and secretaries—these women had seen the horrors of war up close, but they had not been soldiers on the front lines. Now, as prisoners of war, they were transported to Camp Hearn, a new facility in Texas, to work, as part of the Americans’ prisoner repatriation efforts.

The camp was under construction, and the air was thick with the stifling heat of the Texan sun. The women, confused and scared, shuffled toward the processing building, each one shackled and treated as less than human. They were part of the enemy, prisoners of a war they hadn’t chosen. They were supposed to be treated with disdain, as enemies who had committed unspeakable atrocities. They had heard the stories, the propaganda that depicted Americans as cruel, starving, and weak. They had been told that their captivity in the United States would be nothing short of hell.

But then, something unexpected happened.

As the women were processed, a cowboy walked toward them. He wasn’t carrying a weapon. Instead, he carried bolt cutters. The sight of the tool seemed out of place in this environment of barbed wire and guards. He stood before the women, looked at their chained wrists, and uttered five simple words that would change everything: “You won’t need these here.”

The chains fell to the ground with a loud metallic clink. Elsa, one of the women, froze. She couldn’t speak. She couldn’t move. She looked at her fellow prisoners, and their faces reflected the same disbelief. For the first time in weeks, they were free—free from the physical restraint of the chains that had bound them for so long. But the true significance of those words went far beyond the removal of metal links. These five words shattered everything they had been taught about their enemies.

The cowboy who had spoken was Jack Morrison, a 59-year-old cattle rancher who owned a sprawling 5,000-acre ranch just outside of Camp Hearn. Like many ranchers in Texas, Morrison had faced a labor shortage due to the war, and the United States government had placed prisoners of war in camps to work on farms and ranches across the country. Morrison had come to Camp Hearn to take on several of these German prisoners, and he had seen them not as enemies, but as people—people in need of work, just like himself.

Morrison wasn’t interested in treating these women like the enemy. He had heard of the atrocities committed by Nazi forces, but he had also learned that not every person who wore a uniform was guilty of the same crimes. His stance was simple: if these women were to work on his ranch, they would need to be able to do so without the risk of being injured by their chains. After a brief discussion with the camp commandant, Morrison made it clear: if the women were too dangerous to be unchained, then he would find other laborers. The chains came off.

The impact was immediate. Elsa and the other women couldn’t believe it. For the first time in their lives as prisoners, they were treated with something resembling respect. Their wrists, once raw and bloody, were now free. Their bodies, for the first time in weeks, were allowed to move without restraint. The chains that had defined their captivity—the symbol of their status as prisoners—were gone.

Morrison’s actions were not just about physical freedom; they were about dignity. He treated these women as people first, prisoners second. He didn’t see them through the lens of national enemies. Instead, he saw workers who could contribute to his ranch, just like any other employee. As he led them to the ranch, he explained the work they would do—tending to livestock, repairing fences, and helping with the vegetable garden. It was hard labor, but it was honest work. And it was work done without the constant reminder of their status as prisoners.

The women, still stunned by the removal of their chains, found themselves in a world completely different from what they had expected. They worked long hours in the blazing Texas heat, hauling hay bales, pumping water, and caring for cattle. The work was exhausting, but it was also liberating. There were no guards looming over them. They were not shackled. They were simply workers, doing the same jobs that many other people in Texas were doing at the time.

At lunch, they were served sandwiches made with thick bread and fresh meat, something they hadn’t seen in years. They were given cold lemonade, sweet and tart, a stark contrast to the tepid water they had been used to in the prisoner camps. For the first time in what felt like forever, they were treated like human beings, not enemies.

The kindness did not stop there. The women quickly realized that Morrison’s wife, Sarah, was just as kind as her husband. She made sure they had enough food, treated them with respect, and even spoke to them with the kindness of someone who had no interest in the war or the politics behind it. For Elsa, Hilda, and the other women, this was a revelation. They had been taught that Americans were monsters, that they would treat them with cruelty and disdain. Instead, they were met with hospitality and care.

As the work days passed, something shifted within the women. They began to see their captors not as enemies, but as people. They were doing hard work alongside them, but they were also sharing moments of humanity—small gestures of kindness that had nothing to do with the war. A glass of lemonade, a helping hand, a word of encouragement.

For Elsa, this transformation was profound. She had been raised to believe in the superiority of her country, to believe that Germany was destined for victory and that their enemies were weak, inferior. But now, standing in the Texas sun, working on a ranch, she realized that what she had been taught was a lie. The Americans were not weak. They were strong, they were resilient, and they treated people with dignity, regardless of which side of the war they were on.

As the war wound down, and news of Germany’s defeat reached the camp, Elsa and the other women began to understand something even more important. The war was not just about nations clashing; it was about individuals—people trying to survive, trying to make sense of a world that had gone mad. And in the midst of that madness, Jack Morrison had shown them that kindness could still exist. He had treated them as people first, not as enemies. And in doing so, he had changed their lives forever.

Elsa, like many of the women at Camp Hearn, would return to Germany in 1945, but she would carry the lessons she had learned in Texas with her. The chains had been removed not just from her wrists, but from her mind. She would never again view the world through the same lens of propaganda and hatred. She had seen the truth, and it had come to her not through politics, but through the simple act of a Texas rancher treating her with humanity.

And when Elsa looked back on those days in the scorching Texas sun, she remembered the moment the chains fell to the ground. It was a moment that would forever change her—and all the women who had stood there beside her. The chains had been removed, not just physically, but symbolically, and they would never be the same again.