PART II — “The Price of Freedom”

The winter of 1860 in Cincinnati was harsher than any cold I had known along the Mississippi River. The wind cut through the wooden boards of our tiny rented room, and the snow piled so high outside our door that for days at a time we could barely step out. Yet even in that bleakness, there was a kind of warmth—freedom, fragile and trembling, but real.

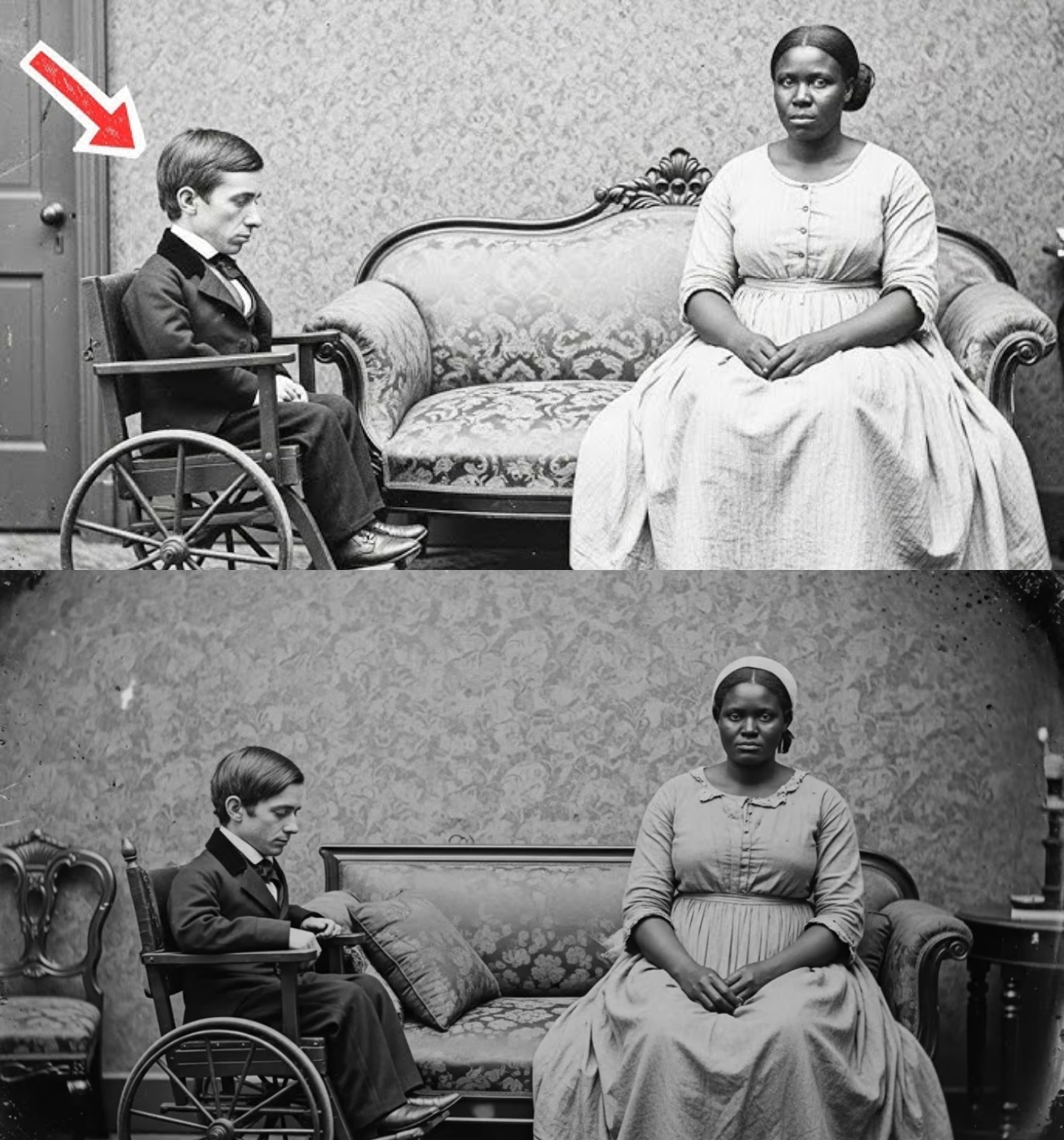

Delilah adapted faster than I did. She had always been stronger—physically, mentally, spiritually. While I struggled with my health, shivering under thick quilts, she attended abolitionist meetings at Zion Baptist Church, carrying messages between organizers, memorizing routes, signals, and names. People trusted her instantly. Her calm presence, her ability to listen without judgment, made her indispensable.

“Thomas,” she told me one evening as she warmed her hands near the small iron stove, “freedom ain’t something you receive once. It’s something you defend every day.”

I admired her. I depended on her. And in truth, part of me feared I held her back.

The Hunters Come North

Freedom had its price—and in March 1860, the price came due.

Slave catchers had arrived in Cincinnati. Word spread among the Black community like wildfire: two men from Mississippi were searching for a runaway woman in her twenties and a frail white man who was “likely to collapse if yelled at too loudly.” The description was unmistakable.

My first instinct was to panic. Delilah’s was to plan.

“We ain’t running again,” she said with absolute certainty. “This time, we stand.”

I had spent my childhood watching my father manipulate laws like clay. Now, in a cruel twist of fate, those same laws—the Fugitive Slave Act—threatened to drag us back into chains. As a white man, I could not be enslaved, but Delilah could be captured, whipped, sold, and forced back into the life we had barely escaped.

I couldn’t let that happen.

A Courtroom of Enemies

With the help of a local abolitionist lawyer, Mr. Jonathan Pearce, we prepared a legal defense for Delilah. It was a desperate, almost foolish plan—Black people, free or enslaved, had no voice in courtrooms controlled by Southern-leaning judges.

The hearing took place on April 12, 1860, in a crowded courtroom thick with the smell of sweat, ink, and hostility. White men—some pro-slavery, some merely curious—filled every seat. Delilah sat beside me, her hands steady, her eyes calm. I trembled so hard my spectacles shook.

The slave catcher, a man named Clayborne Riggs, took the stand first. He held a bill of sale from Callahan Plantation, naming Delilah as property.

Property.

The word made my stomach twist.

Pearce called me to the stand. I felt every eye on me as I walked forward—some mocking, some skeptical, some confused that a man so weak and small could possibly be the husband of the woman beside me.

“State your name,” the judge commanded.

“Thomas Bowmont Callahan,” I answered, my voice cracking.

Gasps rippled through the courtroom. The slave catchers stared at me with shock and then dawning fury.

“You claim to be the son of Judge William Callahan?” the judge asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And Delilah… is my wife.”

The uproar that followed shook the room. Men shouted. Some laughed. Others cursed. The judge slammed his gavel repeatedly until silence was restored.

I testified for nearly an hour—explaining our escape, my father’s plan to use Delilah as breeding stock, our journey north, our marriage in Ohio. Pearce knew my testimony could not legally free Delilah—Black women married to white men were still considered property in slave states—but it could sway public opinion, forcing the judge to consider consequences beyond his bench.

When Delilah was finally allowed to speak, she rose slowly.

“I ain’t property,” she said simply. “Not now, not ever again.”

Her voice—calm, unwavering—cut through the courtroom like a blade. Even the judge seemed moved.

A Decision That Changed Our Lives

After hours of deliberation, the judge delivered his ruling.

Because Delilah had been residing in Ohio for more than six months

—and because her marriage to a white citizen was recognized under Ohio law—

she would not be returned to slavery.

We won.

Not because of justice, not because the law cared about us—but because of a technicality and the fear of an angry abolitionist mob waiting outside.

Riggs and his men left the courtroom empty-handed, spitting curses as they went.

Delilah squeezed my hand. “We’re free,” she whispered.

But freedom came with consequences.

A Target on Our Backs

Two days later, we received news from a traveling abolitionist: my father had publicly disowned me. He declared me “dead by dishonor” in The Natchez Courier. A bounty of $3,000 was placed on Delilah’s capture and return.

“What do we do now?” I asked Delilah.

She looked at me, her eyes filled with certainty.

“We fight harder.”

And we did.

That summer, we joined the most dangerous branch of the Underground Railroad—the night riders who escorted fugitives through the forests of Ohio into Canada. Delilah walked miles in the dark with terrified families. I used my legal training to forge documents, predict patrol routes, and argue with border agents.

Every night, we risked our lives.

Every night, we felt my father’s shadow behind us.

Every night, we chose freedom again.

A New Beginning

On September 1, 1860, a woman arrived at our door carrying a newborn baby wrapped in a worn cotton blanket. She was a runaway who had given birth on her journey north.

“I can’t keep him safe,” she sobbed. “Please… can you?”

Delilah lifted the baby into her arms, rocking him gently. He was small, fragile—like I once was.

“We’ll raise him,” she whispered.

And so we did.

He became our first child, the beginning of a family forged not by blood, but by choice, courage, and love.

Our story was only beginning.