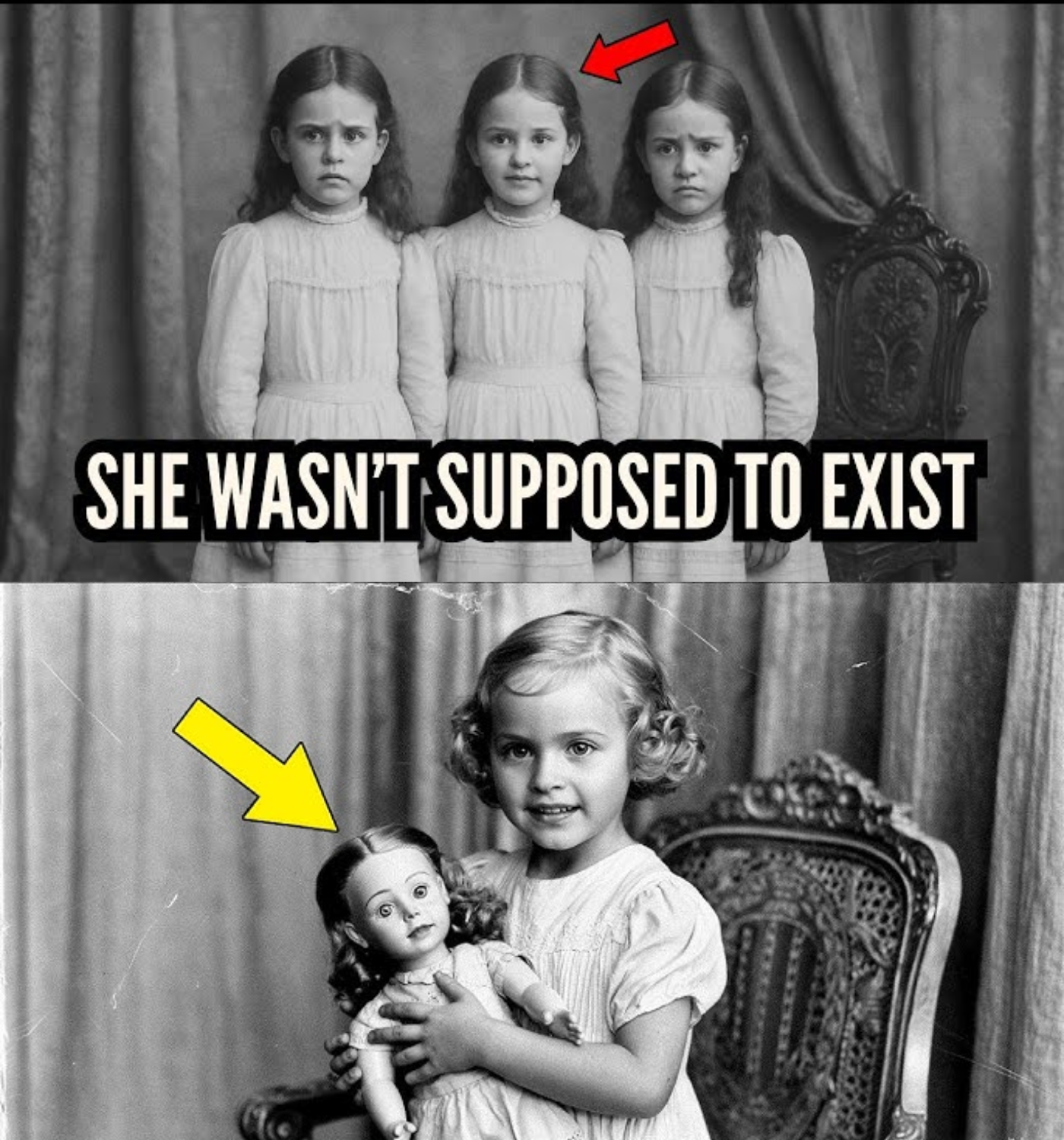

1902 Portrait of Three Sisters… But the Census Only Lists Two Daughters.

.

.

In a dusty archive, a photograph from 1902 captures three young girls, their sepia tones faded yet still striking. They wear fine Edwardian dresses, their hair meticulously styled, and they stare at the camera with innocent smiles. The studio stamp on the back reads “Sterling Photography 1902,” and a handwritten note identifies them as the daughters of Killian and Adelina Walsh. Yet, a glaring discrepancy looms over this seemingly innocent image: the 1900 federal census lists only two daughters in the Walsh household, not three. This revelation raises a troubling question: where is the third daughter?

Grady, a dedicated historical genealogist, takes on the investigation. Armed with the photograph and the census data, he dives into the mystery. Both documents are authentic and dated, but they cannot coexist without conflict. Thus begins Grady’s quest to uncover the truth about the missing daughter.

Killian Walsh and his wife, Adelina, were respectable members of their community, living in a modest home. Killian worked as a clerk, while Adelina managed their household. They appeared to be an ordinary family, living ordinary lives. The 1900 census tells their story in neat columns: Killian, age 32; Adelina, age 29; Rebecca, age five; and Heidi, age one. Four people, two parents, and two daughters—no more, no less.

Ryland, an archivist at the County Historical Society, pulls the census record from the microfilm. The page is legible, and the handwriting is clear. The enumerator visited the Walsh home in June of 1900, and the official record is irrefutable. Errors in census records are common, but omitting an entire child is not. This is a significant discrepancy, and Grady feels the weight of the missing child pressing down on him.

To explore further, Grady takes the photograph to Kylo, a photo analyst specializing in historical images. Under magnification, Kylo examines the girls’ faces, their clothing, and their posture. The eldest girl sits on the left, the youngest on the right, and the middle girl—the mystery girl—sits between them. Kylo estimates their ages: the eldest is about seven, the youngest around three, and the middle girl appears to be five.

Grady does the math. If the photograph was taken in 1902, the ages align perfectly with the census records. Rebecca, the eldest, was born in 1895, and Heidi, the youngest, was born in 1899. But who is the middle girl? Kylo notes that all three girls wear similar, expensive dresses, suggesting they are from the same family. Their physical resemblance is undeniable; they share similar facial features, indicating they are indeed sisters.

Ryland explains the census process: enumerators went door-to-door, asking questions and recording answers. The head of the household provided the information. Children living in the home on census day were to be recorded. Grady realizes that if the third daughter was away visiting relatives, she might not have been counted, but the absence of a five-year-old child in the official record feels like a profound loss.

Determined, Grady searches vital records for the county—birth certificates, death certificates, any official document that might explain the missing girl. He finds records for Rebecca and Heidi but nothing for a third daughter. He searches neighboring counties and looks under various spellings, but there are no matches. He even checks death records, hoping to find evidence of a child who might have been born and died young, but again, he finds nothing.

Frustrated but undeterred, Grady returns to the local historical society and asks Ryland for any personal papers from the Walsh family. Ryland leads him to a small collection of letters and receipts donated by a distant relative. Grady sits down and begins to read through them. Most letters discuss mundane topics, but then he finds a letter from Adelina to her sister, Julieta, dated September 1901.

In neat cursive, Adelina writes about her health, Killian’s work, and the children. Then she writes a poignant line: “I think of her every day. I pray that one day I will have all my girls together under one roof.” Grady’s heart races. This is the first direct evidence that a third daughter existed. Adelina grieved, and she held onto hope. But why was this child not at home? Why was she absent from the census?

Grady considers a new possibility: perhaps the third girl in the photograph is not a daughter at all but a cousin or relative visiting for the portrait. He asks Eduardo, another genealogist, to trace Julieta’s family tree. Eduardo quickly finds Julieta’s family; she married a man named Ricardo, and they had three children, one of whom was a daughter named Aria, born in 1897.

Grady feels a surge of hope. If Aria was visiting her aunt Adelina, it could explain the presence of the third girl in the photograph. However, when Grady locates the 1900 census record for Julieta’s family, he finds Aria listed living with her parents in a town 30 miles away. While she could have visited in 1902, there is no direct evidence to support this theory.

Ryland finds a 1903 portrait of Julieta and her children, which includes Aria. Grady compares the images, but Kylo concludes that the two girls are not the same person. The mystery girl in the Walsh portrait is not Aria. The cousin theory collapses, leaving Grady frustrated and bewildered.

After weeks of investigation, Grady realizes he is missing a crucial piece of the puzzle. He returns to the county archives and asks Ryland to pull the entire 1900 census records, not just the population schedule. Ryland is puzzled but complies. Grady explains that the census included special schedules for specific populations, such as those in institutions.

Ryland retrieves the special schedules, and Grady begins to read through them. He scans the names listed in the county home for incurables and suddenly stops. There it is: Esme Walsh, age three, daughter of Killian and Adelina Walsh, resident of the county home for incurables since 1898. Grady’s hands tremble as he realizes the truth. Esme was there all along, counted in the institutional census but absent from the household census.

Grady contacts Aisha, a social historian, to explain the county home for incurables. Aisha details how, at the turn of the 20th century, families faced difficult choices regarding children with disabilities. Many opted to place their children in institutions due to societal stigma and lack of resources. The county home for incurables housed those with chronic illnesses and disabilities, and Esme lived there permanently.

The revelation transforms Grady’s understanding of the Walsh family. Adelina’s letter now takes on a deeper meaning. She was not speaking hypothetically; she was expressing her longing for Esme to be home. In 1902, Killian and Adelina made a decision to bring Esme home for the day. They dressed her in a beautiful dress and took her to the photographer, capturing the only moment all three sisters were together.

The photograph is not merely a family portrait; it is a declaration of love and defiance against societal norms. It preserves the truth that official records often obscure. Grady writes his final report, including copies of the census, the photograph, the letter, and the institutional records. He reflects on the power of photographs as evidence and testimony from the past.

When Grady posts his findings online, the response is overwhelming. People share their own stories of hidden relatives and family members who were institutionalized. The flood of narratives reveals a pattern—families like the Walshes, who loved but could not openly acknowledge their children with disabilities. Grady realizes this is not just the Walsh family story; it is a broader phenomenon that deserves attention.

He decides to continue his research, searching for more families like the Walshes and uncovering more hidden truths. Grady ends his post with a call to action: to examine family photographs carefully and uncover the stories that might be waiting to be told. The past is complex, and the truth often lies in the details, in the contradictions, and in the photographs that do not match the official narrative.

Through his work, Grady honors the memory of Esme Walsh and all the hidden children like her. He reminds us that every family story deserves to be told, every child deserves to be remembered, and every photograph has the power to reveal the truths that history often tries to forget.