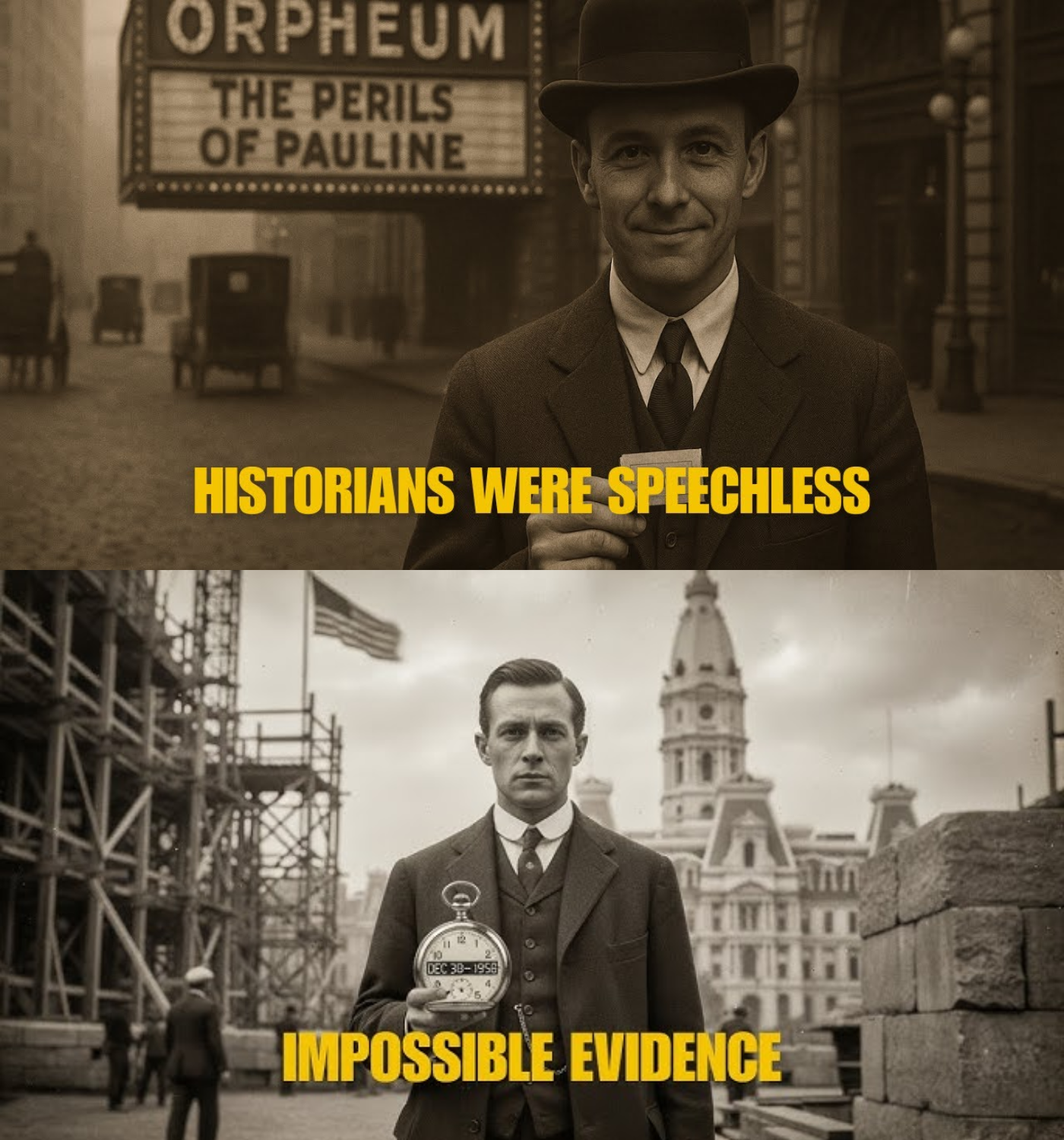

A Man Holds a Ticket in 1914 — And What Appears in the Photo Is Impossible

.

.

In the summer of 1914, outside the Oreium Theater in downtown Chicago, a street photographer named Samuel Reeves captured what would later be known as one of the most disturbing images in American archival history. The photograph depicts a man in a wool suit and bowler hat, holding a movie ticket between his fingers, his smile slight and almost shy. Behind him, the theater’s marquee advertised a silent film titled The Perils of Pauline. The cobblestone street, gas lamps, and horse-drawn carriages all belonged to that era, creating a vivid snapshot of a moment long past.

However, one impossible detail would not be discovered for over a century. Fast forward to a gray October morning in 2019, when Dr. Beatatrice Klene, a curator at the Chicago Historical Archive, was digitizing a collection of early 20th-century photographs. As she scanned the image of the man outside the Oreium Theater at high resolution, she noticed something odd. When she zoomed in on the ticket he held, her coffee cup slipped from her hand, shattering on the hardwood floor. There, printed clearly on the aged ticket stub, was a barcode—a modern UPC barcode that didn’t exist until the 1970s and wouldn’t become standard on event tickets until the 1990s.

Beatatrice sat frozen in her chair, her heart racing. She had worked with historical documents for 15 years and knew about photo manipulation and hoaxes. But this photograph was part of a sealed collection donated by the estate of Samuel Reeves, who had died in 1923. The negatives were stored in their original tin cases, untouched and authenticated by multiple archivists over the decades. The photographic paper dated to 1914, and everything confirmed its authenticity—except for the barcode.

Panic and curiosity surged within her. She called her colleague, Dr. Marcus Webb, a forensic photography expert from Northwestern University. When he arrived two hours later, his skepticism evaporated as he examined the image under magnification. “This isn’t a double exposure,” he muttered, adjusting his glasses. “There’s no layering or inconsistency in the grain pattern. If someone added this digitally, they’d need technology that doesn’t exist yet.”

They worked through the night, running every test they could conceive. Spectral analysis, edge detection algorithms, pixel-level examination—nothing suggested manipulation. The barcode existed in the photograph as genuinely as the man’s face or the theater behind him. By dawn, they had to accept the unacceptable: either they were witnessing the most sophisticated hoax in history, or they were looking at evidence of something far more disturbing.

Three days later, while cataloging the rest of Samuel Reeves’s collection, Beatatrice found something else. Tucked behind a stack of portrait negatives was a small metal film canister labeled “Oreium, October 1914. Do not open.” Trembling, she unsealed it. Inside were 23 feet of deteriorated 35 mm film—not photographic film, but motion picture film used in early cinema. The emulsion was cracked and brittle, barely holding together.

After six weeks of stabilization and digitization, what they found made the barcode seem almost mundane. The film showed the same scene outside the Oreium Theater, but now it was alive and moving. The man with the ticket appeared again, checking his pocket watch. Behind him, the marquee gleamed in the afternoon sunlight. People passed by in period clothing, their movements captured in the jerky, silent poetry of early cinema.

Then, in frame 247, something appeared that made Beatatrice’s blood run cold. A woman walked past the man, moving through the crowd. She was young, dressed in clothes that didn’t match the era—fitted jacket with a strange synthetic sheen, pants instead of a skirt, and shoes with thick rubber soles. In her hand, she held a small rectangular device that glowed faintly: a smartphone.

Beatatrice watched the footage repeatedly, struggling to process what she was seeing. The woman glanced at the device, her fingers moving across its surface in a gesture anyone in the 21st century would recognize instantly—she was scrolling. But this was 1914. The device in her hand wouldn’t be invented for another 90 years.

Marcus arrived within the hour. They sat in the darkened viewing room, watching the footage loop on the screen. “Could this be a student film?” Marcus suggested uncertainly. “Some kind of period recreation shot on authentic 1914 film stock?”

“No,” Beatatrice countered, “the emulsion degradation matches a century of aging. This footage is real.”

Then she advanced the footage frame by frame. At frame 312, another figure appeared in the background, partially obscured by pedestrians—a man in modern clothing, jeans, a hoodie, and white sneakers, holding a sleek digital SLR camera, photographing the man with the ticket.

“Someone documented this,” Beatatrice whispered, horrified. “Someone from our time traveled back and filmed it happening.”

“That’s impossible,” Marcus said, pacing the small room. “Time travel is—”

“Science fiction?” Beatatrice challenged. “Then explain the barcode. Explain the smartphone. Explain why we have footage from 1914 that shows people from our future documenting their own past.”

Over the following months, Beatatrice became obsessed. She expanded her investigation, searching through Chicago’s vast historical archives for any other anomalies. She found them—a 1912 photograph of a street fair featuring what appeared to be plastic bottles, a 1917 image of children playing near the Chicago River with someone wearing modern sunglasses, and a 1920 newspaper photograph of a building fire where a spectator wore a digital wristwatch. All authenticated, all impossible.

But it was another discovery in Reeves’ collection that transformed the mystery from curiosity to something darker. Hidden in a leather portfolio were handwritten notes dated October 8, 1914, in Samuel Reeves’s own hand. He wrote about being paid $20—more money than he’d make in two months—to photograph the man by the ticket booth, emphasizing its importance without explaining why. The note hinted at knowledge of Reeves’s family struggles, suggesting that the person who hired him knew details about his life that no stranger should.

Beatatrice’s heart raced as she read the note. Someone had paid Samuel Reeves to take that specific photograph at that specific time—someone who knew the future. But why?

Digging deeper into the Oreium Theater’s history, she discovered that just four days after Samuel Reeves took the mysterious photograph, tragedy struck. During an evening screening, the massive iron marquee collapsed, killing the theater’s projectionist, Robert Callahan, and injuring several others. The investigation ruled it a tragic accident due to structural failure.

But one detail made Beatatrice stop breathing: Robert Callahan had left behind a pregnant wife, Elena. A quick search confirmed that Elena gave birth to a daughter in February 1915, who grew up to become a philanthropist. In 1972, she established the Callahan Foundation for Scientific Research, which funded numerous studies in theoretical physics, including proposals for temporal mechanics research.

Beatatrice sat back, the pieces clicking together. Robert Callahan’s death had been the catalyst for everything—the foundation, the funding, the research that eventually led to time travel. But why photograph the man with the impossible ticket? The realization hit her like a cold wave: preventing Robert Callahan’s death would erase the foundation, the funding, the research that made time travel possible.

A paradox—a closed loop where causality consumed itself.

“Someone from the future discovered that Robert Callahan’s death was necessary,” she explained to Marcus when he returned. “They documented it, watched it happen, and did nothing. Maybe they tried to change it at first, but then they realized they couldn’t. Or maybe they caused it.”

“That’s murder,” Marcus whispered.

“Is it?” Beatatrice countered. “If you travel back in time and allow someone to die so you can exist, are you a murderer or just a prisoner of causality?”

They sat in silence, contemplating the moral abyss.

Beatatrice spent the next six months searching for more evidence, examining the restored footage frame by frame. In the final frames, she spotted the man in modern clothing, the one with the digital camera, turning toward Samuel Reeves’s position. For three frames, his face was visible. Using facial recognition software, she discovered he was Dr. Nathan Torres, a theoretical physicist who had vanished in 2003 after publishing a controversial paper on temporal paradoxes.

His last known project was a privately funded study on closed timelike curves bankrolled by the Callahan Foundation. Beatatrice contacted his surviving family, who revealed that Nathan had called his sister a week before he disappeared, sounding scared yet excited, claiming he had figured it out—citing a theater in Chicago and someone named Callahan.

Beatatrice’s mind raced. She envisioned Nathan standing in 1914, documenting a death he couldn’t prevent. She thought of Robert Callahan, unaware that his death was already written into the fabric of time, sealed by his daughter’s future generosity and the research it would fund.

One day, Beatatrice received an anonymous package containing a movie ticket stub from the Oreium Theater, dated October 8, 1914. The paper was aged but preserved, with a UPC barcode printed on it—the same barcode from the photograph. Tucked behind it was a typed note:

“The photograph exists because it must exist. Robert Callahan died because his death must exist. You cannot change what has already happened, even if your attempt to change it is part of that very history.”

The warning echoed in her mind, but she was too deep into the mystery to turn back. She had become the question, and somewhere in some tomorrow, someone was preparing to travel back to document this moment, ensuring everything happened exactly as it had to.

Beatatrice returned to the photograph one last time, examining the marquee above the Oreium Theater. In the October 8 image, the iron structure appeared damaged, yet in other scans, it looked pristine. The negative seemed to contain both states simultaneously, as if reality itself couldn’t decide which version was true.

She documented everything meticulously, backing it up to a secure server and leaving copies with trusted colleagues. Then she waited, but nothing happened. No mysterious visitors, no threats—just silence.

Late at night, she would sometimes pull up the photographs, watching the marquee flicker between damaged and pristine, reality flickering, causality uncertain. She began having dreams where she stood outside the Oreium Theater, watching Robert Callahan enter, unaware of his impending death. In these dreams, she could shout a warning, but she never did. Instead, she watched silently, as trapped as the ghosts in Samuel Reeves’s silver halide crystals.

Finally, she went to the Callahan Foundation, presenting her research to Gerald Moss, the current director. He listened patiently before revealing the truth: Martha Callahan had received a visitor—a physicist who explained that preventing her father’s death would erase everything, including her own existence. She chose knowledge over miracle, accepting her father’s death as necessary.

Beatatrice left the meeting feeling hollow, contemplating the choices made across time. She thought of Nathan Torres, of Robert Callahan, and the man in the photograph holding a ticket with an impossible barcode.

That night, she zoomed in on the marquee, watching it twist between realities. The timeline held, and as she saved the file, she realized she was part of a perfect circle—a closed loop of causality. Somewhere, someone was preparing to travel back to document this moment, ensuring that everything happened exactly as it had to.

In her locked drawer, Beatatrice kept the movie ticket stub with the barcode, proof that tomorrow had already touched yesterday, that certain deaths echoed forward and backward simultaneously, forever trapped in the amber of time’s cruel paradox. The photograph remained, the man smiled, and the marquee twisted in the wind—or didn’t—depending on who looked and when, and what version of reality they chose to believe.