Bigfoot Finally Spoke About Humans, What He Said Will Shock You! – Sasquatch Story

.

.

I never thought I’d be the one to tell this story. For thirty years, I kept my mouth shut about what happened to me in the Cascade Mountains. But with all the recent sightings making the news, I can’t stay quiet anymore. People need to know what’s really out there. What I’m about to share will change everything you think you know about these creatures.

Back in the early ’90s, I was obsessed with solo hiking—not just your typical weekend warrior stuff, but venturing into the most remote, dangerous trails imaginable. My friends thought I was crazy, but I lived for that rush. The more isolated and risky the trail, the better. I spent weeks planning these trips, studying topographic maps, searching for areas that barely appeared in hiking guides. I wanted to go where no one else dared.

This particular trip was supposed to be my most ambitious yet: three days deep into the Cascades, following old logging roads that hadn’t seen maintenance in decades. No cell coverage, no marked trails—just me and the wilderness. The first two days went perfectly. I covered good ground, set up camp in spots that probably hadn’t seen a human footprint in years, and the weather was ideal. I felt that familiar high of being completely disconnected from civilization.

But I should have known something was about to go very wrong. The third day started like any other. I broke camp early, ate a quick breakfast, and began my ascent up a steep rocky slope. The plan was to reach a ridgeline that would give me a clear view of the valley below, allowing me to plot my route back to the trailhead. Halfway up, while scrambling over loose rocks, everything went sideways.

My left boot hit a chunk of granite that looked solid, but it shifted the moment I put my weight on it. I felt myself tumbling backward, unable to catch myself. The next thing I knew, I was falling down a fifteen-foot drop, bouncing off rocks on the way down. I hit the bottom hard.

The first thing I noticed was the sound—a wet pop from somewhere inside my left knee that made my stomach churn. When I tried to stand, my leg buckled beneath me. I was at least four miles from my truck, completely off any marked trail. The reality of my situation sank in. Even if I could crawl that distance, which seemed impossible, I’d never make it before dark. The temperature was already dropping, and I knew it would plunge below freezing once the sun set.

I spent the next few hours trying everything I could think of. Crawling got me maybe twenty feet before I was completely exhausted. I fashioned a makeshift walking stick from a dead branch, but putting any weight on my leg sent bolts of pain through my body. By late afternoon, I had to face the truth: I was stuck. As the sun set, I began yelling for help, fully aware it was pointless. Nobody else was crazy enough to be out there, but what else could I do? I screamed until my throat was raw, hoping against hope that maybe another hiker had wandered off the main trails.

When darkness settled in, the temperature plummeted. I had packed for cold weather, but sitting motionless on the ground was different from hiking. The cold seeped through my sleeping bag, and I realized hypothermia was becoming a real threat. Between the pain in my knee and the bone-deep cold, sleep was impossible. That’s when I heard the first sound.

Around midnight, I heard heavy footsteps crashing through the trees, maybe fifty yards away. My first thought was bear, which would have been bad enough. I tried to make myself look bigger, but moving around only made my knee worse. The sounds got closer—branches snapping, leaves rustling—definitely something large moving through the forest. Then it stopped. Complete silence, which felt more terrifying than the noise.

The air around me changed. There was a smell—musky and wild—unlike anything I’d encountered before. I fumbled for my flashlight with shaking hands. When I finally swept the beam across the trees, I saw them: two eyes reflecting the light back at me, glowing like yellow coins in the darkness. But they were wrong—too high up, at least eight feet off the ground. My brain struggled to make sense of what I was seeing. Bears don’t get that tall, even on their hind legs.

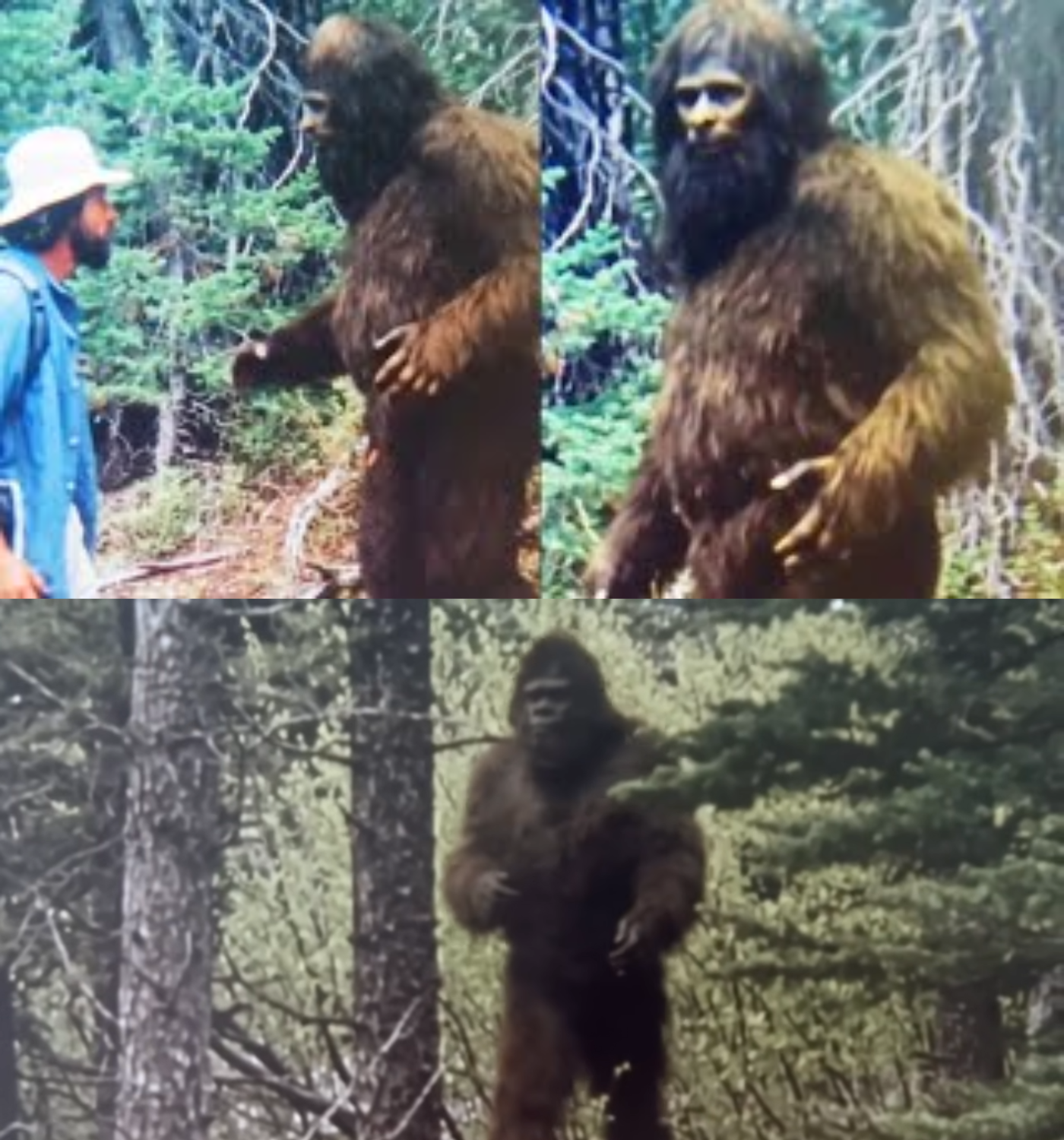

Then it stepped into my light, and every rational thought I’d ever had disappeared. It was massive, easily eight and a half feet tall, covered in dark hair from head to toe. The shoulders were enormous, the arms hung down past where a human’s knees would be, and the chest was barrel-like. But it was the face that really struck me. It wasn’t quite human, but it wasn’t quite animal either. There was intelligence in those eyes, a kind of awareness that made my skin crawl.

It tilted its head slightly, studying me the way you might look at a strange object you found on the ground. I couldn’t move, couldn’t speak, could barely breathe. This creature could have killed me in two seconds, and we both knew it. It made low rumbling sounds, almost like it was talking to itself. The sounds had a rhythm, like language, but nothing I could understand.

Then, something impossible happened. In a voice deeper than any human’s, rough and broken, it said, “You hurt bad.” I thought I was hallucinating. Pain and cold and fear were making me hear things, but it spoke again. “Me see you fall. Long time watching.” The words came out slowly, like each one required effort. The grammar was childlike, but there was no mistaking what I was hearing. This Bigfoot, this thing that shouldn’t exist, was speaking English.

“What?” I managed to croak out. It moved closer, each step shaking the ground slightly. “No, be afraid. Me help. Maybe.” The Bigfoot crouched down about ten feet away, keeping its distance but clearly examining my injured leg. It made concerned grunting sounds like a doctor looking at a patient.

“What do you want?” I finally asked. “Want nothing? You die here that bad?” I stared at this impossible being, my mind racing to process what was happening. “How do you speak English?” The Bigfoot tilted its massive head, considering the question. “Watch humans long time. Listen when they come to mountains. Learn words slow many seasons.” It pointed to itself with one enormous finger. “Me Dot Dot. How you say curious about human people. Others they hide when humans come. Me, I watch. I listen.”

My fear was slowly being replaced by fascination. This was beyond anything I could have imagined. “How long have you been watching?” I asked. “Since small,” it replied, holding its hand at about chest height to indicate a child. “Father teach me stay hidden. But may always want know about small humans who walk on two legs like us.”

“Your father?” I asked, wincing as a wave of pain shot through my leg. The Bigfoot’s expression darkened. “Father gone now. Humans with loud sticks come to valley where we live. Father try protect family. Humans shoot at him. He run but hurt bad. Die in cave alone.” The sadness in its voice was unmistakable. Whatever these beings were, they felt loss the same way humans did.

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I meant it. It studied my face carefully, trying to gauge my sincerity. “You different than others. Baby, most humans they see us. They run or try to hurt us. You hurt, but you talk to me.”

“Because you’re helping me,” I replied. “Why are you helping me?” The Bigfoot was quiet for a long moment, its massive chest rising and falling with slow breaths. Finally, it spoke. “When I small, human helped me once. Lost in storm, very scared. Human find me, give food, show way home. Never forget kindness.”

This was getting more incredible by the minute. “A human helped you when you were young?” I asked. “Old man with white hair live alone in cabin by river. Me lost three days, very hungry. He find me crying by big rock. Give me bread or milk. Walk with me until I find family trail.” The Bigfoot’s eyes grew distant with the memory. “Family very angry. Say never trust humans, but old man he just won’t help lost child. Me never forget.”

I was beginning to understand why this particular Bigfoot was different from the others. That childhood encounter had shaped its entire view of humanity. “You come back many times to thank him?” I asked. “Watch his cabin from trees. He never see me, but I leave gifts. Good berries, fish from stream. One day, cabin empty, old man gone. Me sad for a long time.”

The Bigfoot looked down at my injured leg again. “You remind me of old man. Alone in mountains, need help. Maybe me pay back kindness now.” As we talked, I learned more about his people than I ever could have imagined. They called themselves something that sounded like “Sabi,” though the Bigfoot admitted the word didn’t translate well to human language. They lived in extended family groups, usually twenty to thirty individuals, scattered throughout the most remote mountain regions.

“We once live everywhere,” the creature explained, gesturing broadly with its massive arms. “Whole mountain range ours. Many, many families now…” It held up fingers, counting. “Maybe eight, ten families left. Others gone, moved far away or dead.”

“What happened?” I asked. “Humans bring noise, bring cutting trees, bring death. We move deeper, higher, but always humans come more.” The Bigfoot described a society under incredible pressure. The older generation wanted to maintain the ancient ways, staying hidden no matter what. The younger ones were split between wanting to fight back and wanting to make contact with humans. The middle generation, like this creature, were caught between the two extremes.

“My brother say humans must all die or we die. Sister say we try talk to humans, make peace. Me not know what right.”

“What do you think?” I asked. The Bigfoot was quiet for so long that I thought it wouldn’t answer. Finally, it spoke. “Me think some humans good, some bad, like my people. Some of us help, some of us hurt. But how tell difference?”

It was a fair question, and one I didn’t have a good answer for. From their perspective, human expansion must look like an invasion. From ours, we were just seeking more space, more resources, more adventure. “Me watch many humans come to mountains,” the Bigfoot continued. “Some take only pictures, leave only footprints. Others cut trees, leave trash, shoot animals for fun. How we know which kind you are?”

“You’re taking a chance on me,” I said. “Yes, maybe bad choice, but old man teach me… sometimes risk worth it.” As our conversation continued, the Bigfoot grew increasingly agitated. It kept looking over its shoulder, nostrils flaring as it tested the air. The distant howling I’d heard earlier was getting closer, and now I could hear crashing sounds in the forest.

“They coming,” the Bigfoot said urgently. “Smell your blood. No human.”

“Who’s coming?” I asked, panic rising in my chest. “Hunting back. Young males who hate humans. They patrol this area, look for any humans who come too far into territory.” The Bigfoot stood up, its massive frame blocking out the stars. “They find you, they kill you slow. Make example. Want other humans know what happen if they come here?”

My blood ran cold. “How many of them?”

“Four, maybe five. All big, all angry. Their leader… he very dangerous. Kill three humans already. Keep pieces as warnings.”

This was getting worse by the minute. “What about you? What happens if they find you helping me?”

The Bigfoot’s expression grew grim. “They call me traitor. Say I betray family. Maybe they kill me too.”

“Then why are you still here?”

“Because old man show me something important. He show me humans and my people not so different. Both love family. Both want live in peace. Both afraid of what we not understand.” The Bigfoot knelt beside me again, its massive hand hovering over my injured leg. “But others, they only see difference. Only see threat. You understand?”

I nodded, realizing the complexity of the situation. This wasn’t just about territorial disputes or resource competition. It was about fundamental worldviews—whether two different species could coexist or were destined to destroy each other.

“Tell me about the others,” I said. “The ones who want to fight.”

The Bigfoot’s face darkened. “They say humans are disease. Spread everywhere. Kill everything. Point to dead rivers, empty forests, animals gone forever. Say only way save our people is remove human disease from Earth.”

“Do you believe that?”

“Me see what they see. Humans do damage, take too much, give nothing back. But me also see humans who care, who try protect wild places, who feel same sadness we feel when forest dies.”

It was a remarkably nuanced view from a being that most humans would dismiss as primitive. “So what’s the answer?” I asked.

“Me not know. Wise elders say hide deeper. Wait for humans destroy themselves. Young fighters say attack first. Drive humans away from mountains. Me think… me think… maybe try something different.”

“Like what?”

The Bigfoot gestured between us. “Like this. Talk instead of fight. Try understand instead of fear. But very dangerous. If my people find out me talk to human…”

The howling was getting closer now, accompanied by the sound of heavy footsteps crashing through the underbrush. The creature’s head snapped up, alert and tense. “No more time for talk. They almost here. Must get you moving now.”

What happened next changed everything I thought I knew about the world. This creature, this Bigfoot, started talking—really talking. Not just broken phrases, but explaining things. Its voice was still rough, the grammar still simple, but the meaning was clear. “My people, we watch humans long time. Some of us won’t help humans. Others want humans gone.”

It explained that his species wasn’t just hiding from us; they were divided about what to do with us. Some, like him, had watched humans for generations and felt a kind of kinship. Others had grown increasingly hostile as human development destroyed more of their territory.

“Others like me, they hurt human who come here,” it warned, glancing nervously toward the dark trees. “They say kill human before human kill us.” The Bigfoot told me about watching forests being cut down, mountains being strip-mined, rivers being polluted. His people had once roamed across vast territories, but now they were squeezed into smaller and smaller areas.

“Humans take everything, leave nothing for us,” it said with genuine sadness. The more it talked, the more I understood how complex their situation was. This Bigfoot was caught between two worlds. He’d watched human hikers and campers who respected the wilderness, who seemed to appreciate the same things his people valued. But he’d also seen the destruction that followed human expansion.

“Me different. Me think human may be not all bad,” he admitted. “But my brother, he say I stupid for help human.”

It described violent arguments within his community about whether to reveal themselves, whether to fight back against human encroachment, or whether to retreat even deeper into hiding. Some wanted war; others wanted to find a way to coexist. Many just wanted to disappear entirely. The internal conflict was tearing his people apart. Families were choosing sides, ancient bonds were breaking, and the hostility toward humans was growing stronger every year.

“They smell you here. They come look maybe,” he said, his voice taking on an urgent tone. “You lucky find me, not find other.”

What the Bigfoot told me next made my blood run cold. The hostile members of his species weren’t just avoiding humans; they were actively hunting them. Injured hikers, solo campers, anyone who wandered too far from the main trails was seen as fair game. “They smell human blood,” he explained, his massive nostrils flaring. “Injured human, easy target.” He described how his people could track a human for days without being detected, how they could move through the forest in complete silence. An injured hiker like me wasn’t just vulnerable; I was practically a sitting duck.

“They come tonight maybe,” he said, constantly scanning the darkness around us. “Me cannot stop them if they decide hurt you.” The Bigfoot became increasingly agitated as he spoke, repeatedly looking over his shoulder into the black forest. Something was making him nervous, and if something that size and power was scared, what chance did I have?

Despite his fears about his own people, despite the danger it put him in, this Bigfoot decided to help me. He disappeared into the forest for a few minutes and returned with an armload of straight branches and tough vines, working with surprising dexterity for such massive hands. He fashioned a crude splint for my leg. The pain was incredible as he positioned the sticks and wrapped them with the vines, but I bit down on a piece of leather from my pack and endured it.

Next, he showed me plants I could eat and pointed out a small stream about fifty yards away where I could get water. He created a makeshift crutch from a strong branch, testing it carefully before handing it to me. “You go now fast as can,” he urged, helping me to my feet. “No, come back this place.”

Standing on the crude crutch, I realized I might actually be able to make it out. The splint gave my leg enough support to bear a little weight, and the crutch took most of the pressure off. It would be slow going, but it was possible.

As I prepared to leave, the Bigfoot grew more anxious. He kept turning his head toward the forest, his nostrils flaring, his massive hands clenching and unclenching. “Others coming,” he said urgently. “They smell human blood.”

In the distance, I heard it—a low howling or more of a scream that didn’t sound like any wolf or coyote I’d ever heard. It was answered by another howl from a different direction. Then another. The sounds were getting closer. I knew these were howls from its species, from all the Bigfoots out there.

“Me cannot stop them,” the Bigfoot repeated, genuine fear in his voice now. “Human world and our world… they cannot touch. Too dangerous.”

He helped me gather my pack and get oriented toward the direction of my truck. The howling was getting louder, and I could hear branches breaking as something large moved through the forest. “Go,” he commanded. “Go now.”

I hobbled away as fast as the crutch would allow, adrenaline overriding the pain in my leg. Behind me, the howling grew louder and more frequent. There were definitely multiple Bigfoots out there, and they were communicating with each other. The crude crutch worked better than I’d hoped, but I was still moving painfully slowly. Every few minutes, I’d hear heavy footsteps that seemed to be pacing me, staying just out of sight in the trees. Whatever was out there was toying with me, letting me know I was being hunted.

As dawn finally broke, I could see my truck in the distance. I’ve never been so happy to see anything in my entire life. I made it to the vehicle just as the sun rose, completely exhausted but alive. I drove straight to the nearest hospital, where I told the doctors I’d fallen while hiking alone. The knee required surgery and months of physical therapy. The official story was that I slipped on loose rocks and crawled back to my truck. Nobody questioned it. I never went solo hiking again.

The mountains that had once called to me now felt threatening and alien. For years, I wondered if I’d imagined the whole encounter. Maybe the pain, cold, and fear had made me hallucinate. Maybe my brain had created the talking creature to help me cope with a hopeless situation. But the splint was real. The crutch was real. And deep down, I knew what I experienced was real too.

For three decades, I kept this story to myself. Who would believe me? Honestly, part of me hoped I’d never have to think about it again. But lately, things have changed. The news is full of Bigfoot sightings. More and more people are reporting encounters in remote areas. Some of these reports sound friendly, even helpful, but others are darker—hikers going missing, campsites found destroyed, signs of something large and aggressive in areas where attacks are happening.

I think the creature I met was right about his people being divided. I think the hostile ones he warned me about are becoming more active. Maybe they’ve decided that hiding isn’t enough anymore. Maybe they’re tired of losing their territory to human expansion. The creature who saved my life told me something important that night: “Human world and our world, they cannot touch. Too dangerous.”

But I think our worlds are touching whether we want them to or not. Human activity is pushing deeper into their last refuges, and they’re being forced to make choices about how to respond. What worries me most is that people don’t understand what they’re dealing with. The hiking forums are full of people planning trips to areas where Bigfoot has been spotted. They think it’s all fun and games, like they’re going to get a cool photo for social media. They have no idea how dangerous some of these creatures can be.

The one I met was at least eight and a half feet tall and probably weighed five hundred pounds. He could have snapped my neck with one hand, and he was one of the friendly ones. The hostile ones don’t see humans as fellow creatures deserving respect. They see us as invaders who have destroyed their world. An injured hiker alone in the wilderness isn’t going to get a rescue; they’re going to get exactly what those creatures think they deserve.

I’m not trying to scare people away from the outdoors. The wilderness is still a beautiful, essential part of our world, but we need to understand that we’re not alone out there. We need to respect the fact that some areas might be better left undisturbed. We need to acknowledge that our expansion into wild places has consequences we’re only beginning to understand.

The creature who saved me talked about his people having to choose between war and coexistence. I think humans are going to have to make that same choice soon. We can keep pushing deeper into the last wild places, forcing confrontations that nobody wants, or we can find ways to share this planet with beings we’re only now beginning to understand.

That creature could have let me die. It would have been easier for him, safer for his people. But he chose compassion over fear, understanding over hostility. He showed me that despite our differences, despite the conflicts between our species, there’s still hope for something better.

I’m telling this story because I think people deserve to know the truth. These creatures exist. They are intelligent, and some of them are running out of patience with us. What happens next depends on the choices we make now. The mountains are still calling to adventurous spirits, just like they called to me thirty years ago. But now I know we’re not the only ones listening to that call.

If we’re not careful, if we don’t start showing more respect for the wild places and the beings that call them home, that call might become something much more dangerous than any of us are prepared to handle. The creature who saved my life gave me more than just a splint and a crutch. He gave me a warning. I’ve carried it with me for thirty years, and now I’m passing it on to you. What you do with it is up to you.