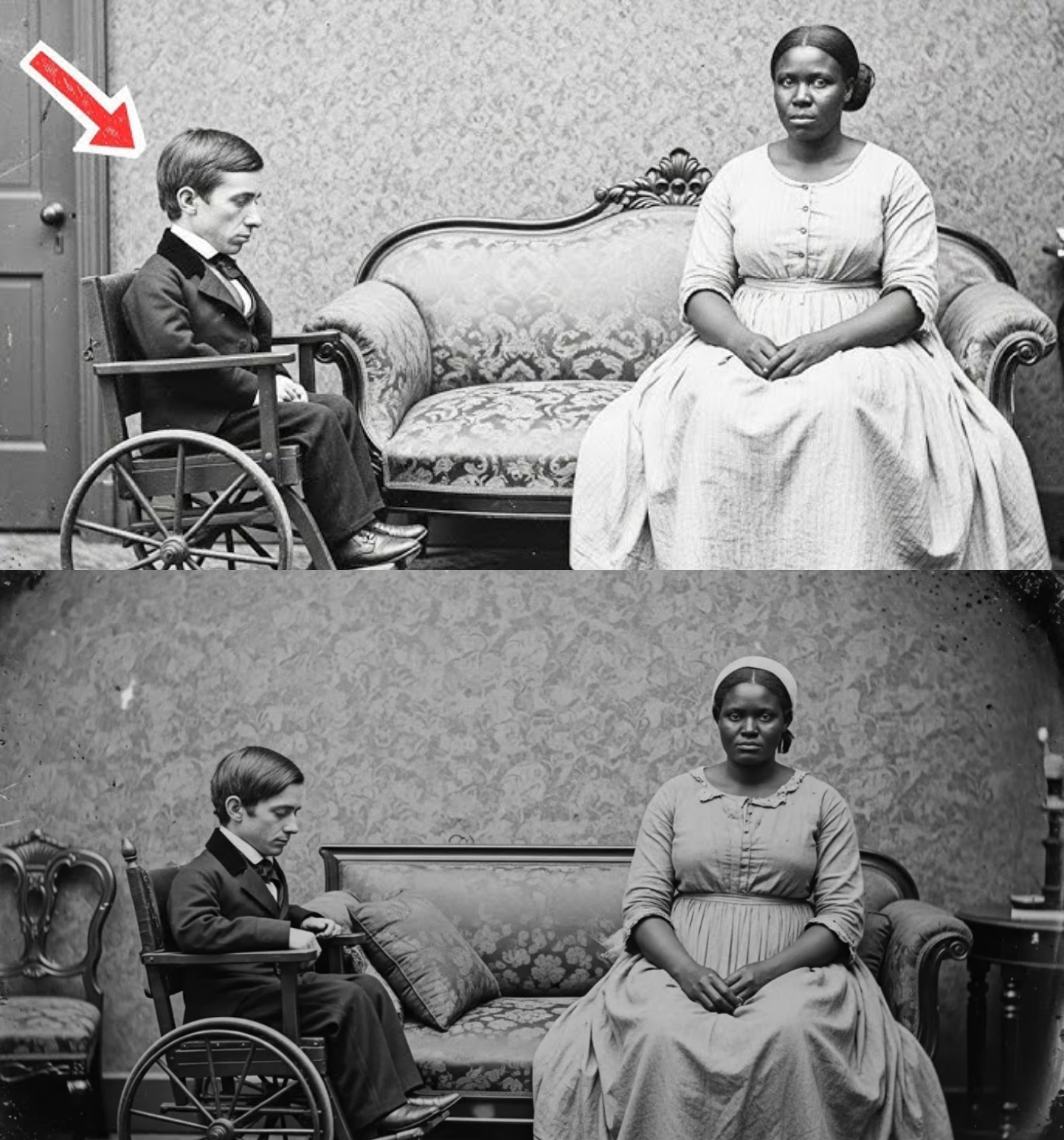

He was considered unfit for reproduction — his father gave him to the strongest enslaved woman 1859

.

.

The Unbreakable Spirit: The Story of Thomas Bowmont Callahan

They called me defective during the toteminovida, and by the age of 19, after three doctors examined my frail body and pronounced their verdict, I started to believe them. My name is Thomas Bowmont Callahan. I was born premature in January 1840, arriving two months early during one of the coldest winters Mississippi had seen in decades. My mother, Sarah Bowmont Callahan, went into labor unexpectedly during a dinner party my father was hosting for visiting judges and planters.

The midwife, an enslaved woman named Mama Ruth, who had delivered half the white babies in the county, took one look at me and shook her head. “Judge Callahan,” she told my father, “this baby won’t make it through the night. He’s too small, too weak. Best prepare your wife for the loss.” But my mother, delirious with fever and exhaustion, refused to accept that prognosis. “He’ll live,” she whispered, holding my tiny body against her chest. “I can feel his heart beating. It’s weak, but it’s fighting.”

And she was right. I survived that first night and the next and the next. But surviving isn’t the same as thriving. At one month, I weighed barely six pounds. At six months, I still couldn’t hold up my own head. At one year, when other babies were standing and some were taking their first steps, I could barely sit upright. The doctors my father brought in from Natchez, Vicksburg, and as far away as New Orleans all said the same thing: premature birth had stunted my development in ways that would affect me for life.

My mother died when I was six years old, a victim of the yellow fever epidemic that swept through Mississippi in 1846. I remember her lying in bed, her skin the color of old parchment, her eyes yellowed and distant. She called me to her bedside the day before she died. “Thomas,” she whispered, her voice barely audible, “you’re going to face challenges your whole life. People will underestimate you. They’ll pity you. They’ll dismiss you. But you have something more valuable than physical strength. You have your mind, your heart, your soul. Don’t let anyone make you feel less than whole.” And she died the next morning.

My father, Judge William Callahan, was a formidable man in every way I wasn’t. Six feet tall, broad-shouldered, with a voice that could silence a courtroom with a single word. He built his fortune from nothing, starting as a poor lawyer from Alabama, marrying into the Bowmont family’s modest plantation, and transforming those initial 800 acres into an 8,000-acre cotton empire. Callahan Plantation sat on the high bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, 15 miles south of Natchez, in what was considered the richest soil in the South.

The main house was a Greek Revival mansion my father had built in 1835. Two stories of white-painted brick with massive Doric columns, wide galleries on both levels, and tall windows that caught the river breeze. Inside, crystal chandeliers hung from 15-foot ceilings, and imported furniture filled rooms large enough to host balls for a hundred guests. Behind the main house stretched the working plantation, with the cotton gin, blacksmith shop, carpentry workshop, smokehouse, laundry, kitchen building, overseer’s house, and beyond all that, the quarters—rows of small cabins where 300 enslaved people lived in conditions that contrasted sharply with the mansion’s luxury.

I grew up in this world of extreme wealth built on extreme brutality, though as a child, I didn’t understand the full implications. I was tutored at home by a succession of teachers my father hired. I was too frail for the rough-and-tumble of school, too sickly to board at the academies where other planter sons went. Instead, I learned Greek and Latin, mathematics and literature, history and philosophy in the quiet of my father’s library.

By age 19, I stood 5 feet 2 inches tall, the height of a boy entering puberty rather than a young man. My frame was slight, weighing perhaps 110 pounds, with bones so delicate that Dr. Harrison once commented I had the skeleton of a bird. My chest caved inward slightly, a condition called pectus excavatum, the result of ribs that had never properly formed. My hands trembled constantly, making simple tasks like writing or holding a teacup a challenge. My eyesight was terrible, requiring thick spectacles that magnified my pale blue eyes to an almost comical size. Without them, the world was a blur.

My voice had never fully deepened, remaining in that awkward range between boy and man. My hair was fine and light brown, thinning already despite my youth. My skin was pale, almost translucent, showing every vein beneath the surface. The worst part, however, was my complete lack of masculine development. I had no facial hair to speak of, just a few wispy strands on my upper lip that I shaved more out of hope than necessity. My reproductive organs were severely underdeveloped, rendering me sterile.

The examinations began shortly after my 18th birthday in January 1858. My father had arranged for me to meet a potential bride, Martha Henderson, daughter of a wealthy planter from Port Gibson. The meeting was a disaster. Martha took one look at me and couldn’t hide her disgust. She made polite conversation for exactly 15 minutes before claiming a headache and leaving. I overheard her telling her mother as they departed, “Father can’t seriously expect me to marry that—that child. He looks like he’d break in half on our wedding night.”

After that humiliation, my father summoned Dr. Harrison. Dr. Samuel Harrison was Natchez’s most prominent physician, a Yale-educated man in his 50s who specialized in matters of masculine health and heredity. He conducted the most humiliating hour of my life, measuring me, examining every inch of my body, and writing notes in a small leather journal. His verdict was devastating: severe hypogonadism with associated sterility. The word hung in the air like a death sentence.

Three doctors, three examinations, three identical conclusions. Thomas Bowmont Callahan was sterile, unfit for breeding, incapable of continuing the family line. The news spread through Mississippi’s planter society with the speed of gossip among people who had nothing better to do than discuss each other’s business. My father made no effort to keep it secret. What would be the point? Any woman who agreed to marry me would need to know.

By December 1858, my father had stopped trying. We ate dinner together in silence most nights, the clink of silver on china the only sound in the massive dining room. The explosion came in March 1859 when my father, having been drinking more than usual, proposed giving me Delilah, an enslaved woman on our plantation, as my companion. The words hit me like a physical blow. He wanted me to use her to produce heirs, treating her as breeding stock.

I was horrified. I had spent my life being told I was defective, but this was beyond comprehension. I couldn’t let my father’s plan happen without at least warning Delilah. I made my way to her cabin, prepared to tell her everything. When I finally explained the situation, she listened intently, her expression shifting from shock to resignation. But then she surprised me with her response. She suggested we escape together.

Delilah and I planned our escape over the course of several days. We traveled through the night, avoiding patrols and checkpoints. As we journeyed north, we grew closer, sharing stories and dreams. I found solace in her strength, and she found hope in my determination. By the time we reached Cincinnati, we had forged a bond that transcended our pasts.

In Cincinnati, we reinvented ourselves. We presented ourselves as husband and wife, and despite the challenges we faced, we built a life together. We became part of the Underground Railroad, helping others find freedom while navigating our own complicated existence. In November 1859, we married legally, despite the societal stigma.

Our journey was not without its struggles, but together, we defied the odds. We adopted three children, giving them the love and freedom we had fought so hard to obtain. Delilah became a pillar of strength in our community, advocating for the rights of the newly freed, while I used my legal knowledge to navigate the complexities of our new lives.

As I reflect on our journey, I realize that my body may have been a betrayal, but my spirit was unbreakable. I chose love over convention, dignity over despair, and in doing so, I discovered a life worth living. Our story, a testament to resilience and the power of choice, continues to inspire those who dare to defy the odds and seek freedom against all odds.