The Apaches in World War II Were Far More Brutal Than You Imagine — History Hid Everything

.

.

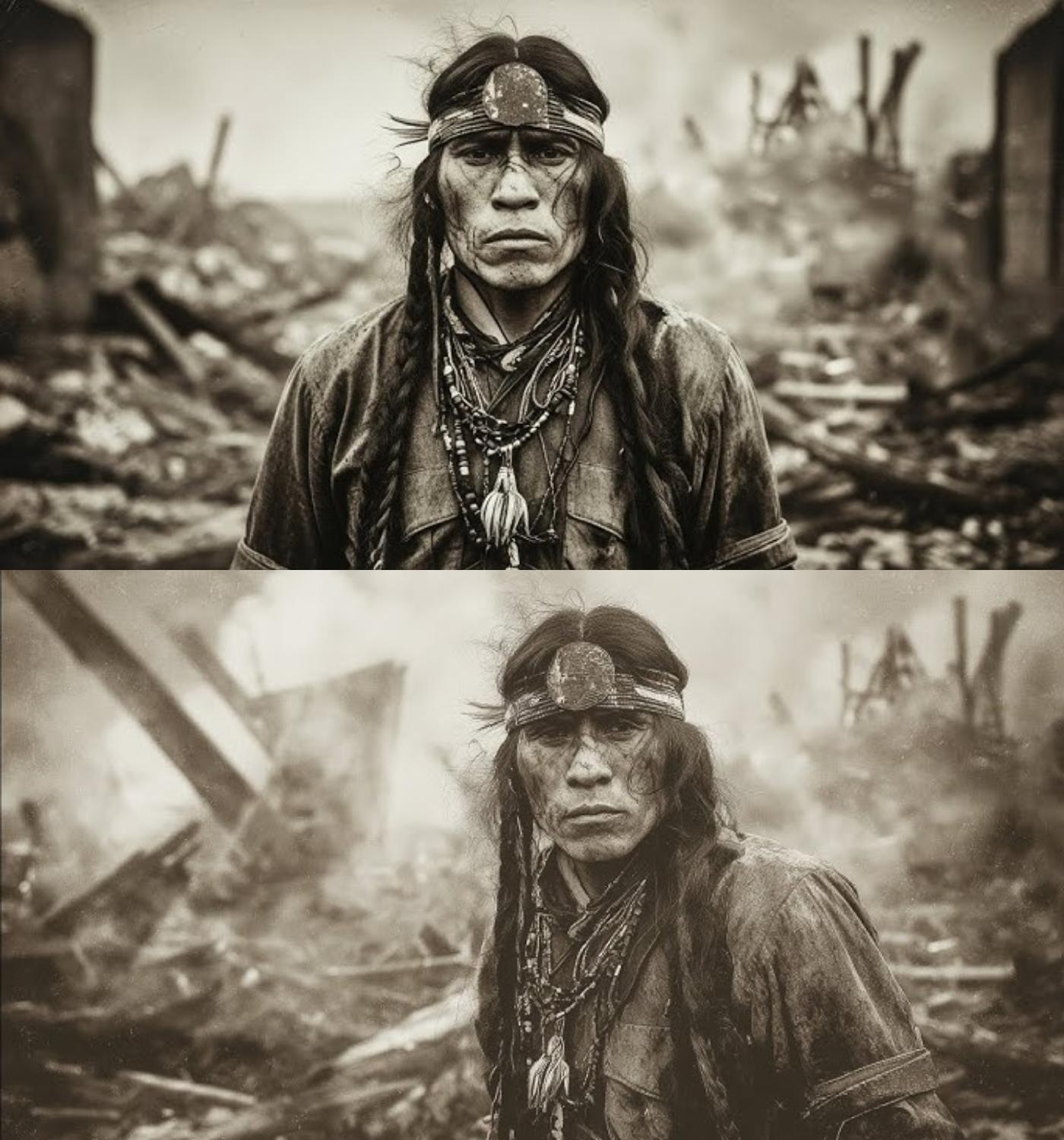

The Shadows of War: A Hidden Legacy

On December 8, 1941, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a telegram arrived at the San Carlos Apache reservation in Arizona, summoning tribal council members to Fort Wuka for a matter of national security. By nightfall, twelve Apache elders had traversed the Sonoran Desert, unaware that their lives—and the lives of many others—would be forever altered.

Inside a windowless conference room, three army officers awaited them. Their uniforms bore no name tags or rank insignias, an unsettling sign of the secrecy surrounding the meeting. The oldest officer, referred to simply as “the colonel,” placed a leather folder on the table but did not open it. His voice trembled slightly as he began, “We are about to ask you to help us win a war using methods that will never be acknowledged by this government or any other.”

The tribal chairman, Joseph Tissosce, studied the colonel’s face carefully before responding. “Our grandfathers knew how to make an enemy afraid of the dark. If you want us to teach your soldiers that art, you must understand it comes with a cost. Once a man learns to move like the wind and kill like the mountain lion, he does not easily return to being a man who sleeps peacefully.”

What the military proposed was far more than the famous Navajo code talkers. This was about weaponizing ancient Apache guerrilla tactics and psychological warfare techniques, creating units that would operate in the deepest shadows of the Pacific and European theaters. This initiative would go undocumented, known only as the Shadow War Initiative.

By January 1942, the first recruits arrived at a newly constructed facility in a box canyon, once Apache hunting grounds. The military sought to immerse the trainees in their ancestral legacy, tapping into primal instincts that could not be taught in conventional boot camps. Of the 147 men who reported for training, only 63 would complete it; the others vanished from military records, their families receiving telegrams stating they had been transferred to classified assignments.

The training was described as beyond anything the military had attempted before. The men learned to navigate without leaving a trace, to survive weeks behind enemy lines, and to inflict psychological terror that would break an enemy’s will long before any physical confrontation. A journal entry from Lieutenant Robert Chen captured the essence of the program: “Today I watched something that made me question whether we are the good guys in this war.”

The first deployment of these Apache units occurred in June 1942, with twelve men inserted into the Philippines. Their official mission was intelligence gathering, but the reality was far darker. They conducted hyper-aggressive psychological operations and targeted assassinations aimed at instilling maximum terror with minimal engagement.

Japanese officer Lieutenant Yamamoto Kenji documented the supernatural terror his men faced, describing how they found Sergeant Nakamura hanging from a tree with no blood on the ground beneath him. His account revealed a growing fear among his troops, who believed they were being hunted by demons. “I do not know what is hunting us,” he wrote, “but it is winning.”

What Yamamoto did not realize was that only two Apache soldiers were responsible for the deaths of his men and the psychological collapse of an entire battalion. They employed traditional stealth methods, augmented by newly developed chemical compounds designed to induce hallucinogenic effects, alongside acoustic devices that generated subsonic frequencies to provoke extreme anxiety.

Back at the training facility, a second wave of recruits underwent even more intensive preparation. By late 1942, the facility housed over 300 trainees and instructors, gaining a disturbing reputation among regular military personnel. Soldiers reported seeing lights in the canyon at odd hours and hearing sounds that defied explanation. Captain James Morrison, the base psychiatrist, filed a report expressing deep concern for the mental health of the trainees, stating, “I cannot identify what is being created in that canyon.”

Between 1942 and 1945, Apache shadow units were deployed to every major theater of the war, operating independently of regular military command. Their methods led to mass desertions and the psychological destruction of enemy units. In the Ardennes Forest during the Battle of the Bulge, a German battalion reported being systematically hunted by ghost soldiers. Oberlitand Hans Richter wrote to his wife, “We are being hunted by something that defies explanation.”

In the Pacific, reports of the “silent ones” emerged, enemy combatants who never spoke or revealed themselves fully. An American Marine Corps after-action report described encountering the aftermath of an Apache operation, where 80 enemy combatants were found dead in a cave, arranged to create maximum psychological impact. The scene was so unsettling that the investigating soldiers refused to remain in the caves.

As the war drew to a close, the military faced an unexpected problem: the men transformed into shadow warriors struggled to reintegrate into civilian life. Reports emerged of Apache unit members becoming unresponsive to commands or attacking friendly forces. A classified medical report described soldiers in a state of combat psychosis, exhibiting extreme trauma but showing no obvious signs of distress.

The military’s solution was cold and pragmatic: they made most of the Apache shadow warriors disappear from official records. Of the 237 men who completed the training, only 68 appear in post-war military records. Their families were told they had died in combat, but no bodies were returned, and no graves were marked. They became ghosts in death as they had been in war.

Throughout the late 1940s and into the 1950s, a disturbing pattern emerged. Young Apache men began vanishing from reservations after being approached by individuals claiming to be military recruiters. Reports filed by tribal police described the same scenario: men who left with promises of special opportunities, only to disappear without a trace.

The shadow warrior program had never truly ended; it had simply gone deeper underground. The Cold War created new demands for operatives capable of conducting operations that left no fingerprints, and the military recognized the value of the techniques developed by the Apache program. Between 1948 and 1963, a continuation program called Night Wind recruited and trained over 100 additional Apache operatives, who were deployed to various conflict zones without any official records.

In Vietnam, stories emerged of American special forces who operated under no known command structure, employing methods that shocked even hardened combat veterans. Captain Raymond Teller recounted discovering an entire Viet Cong company dead without a battle, their faces frozen in terror. “Some had apparently died trying to run,” he noted.

The techniques employed by these operatives blurred the lines between ancient traditions and modern warfare. Declassified research documents revealed extensive studies into compounds that induced extreme fear and paranoia. One summary described a compound referred to as “whisper agent,” which could produce psychological collapse in stable individuals.

In 2004, a former operative named David Knighthorse contacted a journalist to share his story. He described being recruited because of his bloodline and undergoing training that broke down his normal consciousness and rebuilt it into something else. “We learned to tap into something our ancestors warned against becoming,” he said. “Every operation took something from us, made us less human.”

The journalist, Michael Torres, attempted to verify Knighthorse’s claims but faced numerous obstacles. He published articles that were quickly scrubbed from the internet, and he eventually ceased his investigation due to threats to his safety. Torres died in 2009 under suspicious circumstances, his research materials never recovered.

In 2019, a defense department budget document was accidentally released, revealing a single entry for “Heritage Warrior continuation.” Follow-up inquiries were met with vague responses, stating it was related to cultural preservation programs. Yet, reports from conflict zones continued to surface, describing encounters with forces employing tactics remarkably similar to those of the Apache operatives.

The legacy of the Shadow Warrior program lingers, with persistent reports of encounters in Afghanistan and Syria involving forces that move like shadows and instill fear without leaving a trace. Analysts suggest that the techniques pioneered by the Apache program have been adapted by military and intelligence services worldwide.

The reservations where the original operatives were recruited have become places of deep collective trauma. Families live with the knowledge that their loved ones served their country in ways that will never be acknowledged. Some communities held ceremonies to cleanse these men, but the results were mixed. A medicine man noted, “What was done to these men went beyond disturbance. They created beings that exist in between.”

The classified sections of the National Archives reportedly contain entire filing cabinets devoted to the Shadow Warrior program, detailing one of the most extreme military experiments in American history. The question remains: what was created in the process, and can it ever be unmade?

As we reflect on this hidden history, we must remember the sacrifices made by those who served in the shadows. Their stories may never be publicly recognized, but they deserve to be honored. The legacy of the Shadow Warrior program is a reminder of the darkness that can emerge in the pursuit of national security, and the importance of seeking truth and light in a world often shrouded in shadows.