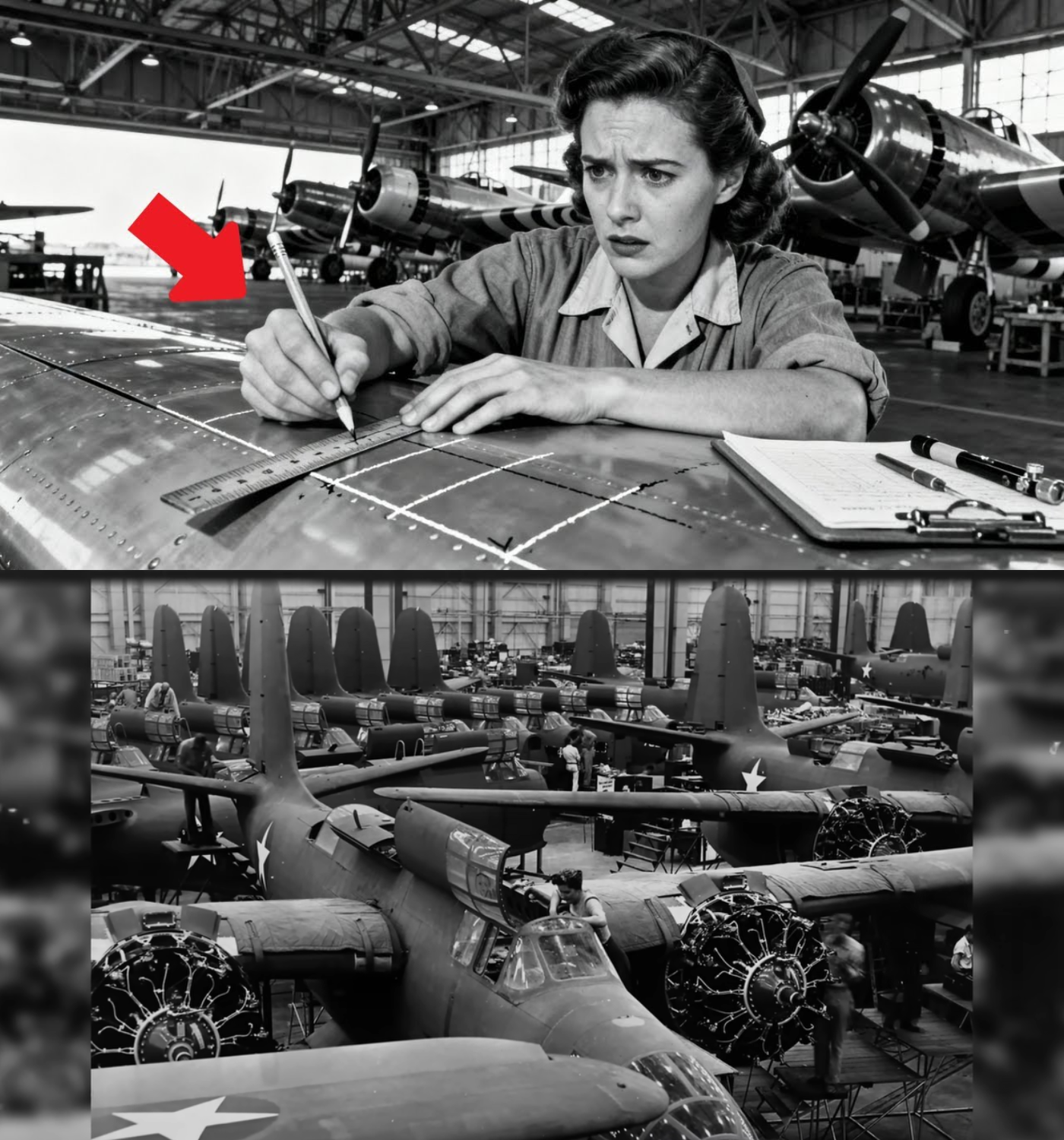

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

.

.

On April 12th, 1943, a cold morning enveloped a bustling plane factory in Long Island. The roar of engines and the screech of rivet guns filled the air, a cacophony that underscored the urgency of wartime production. Beneath a half-built bomber, a young woman named Beatatrice Schilling stood alone, pencil in hand, her hands trembling. Above her, the clock ticked ominously, a reminder that pilots were risking their lives in planes like the one she was inspecting.

The Army Air Forces were brimming with confidence. American planes were being produced at an unprecedented rate, with factories springing up across the nation. From California to Connecticut, Michigan to Texas, bombers rolled off assembly lines, and German pilots had begun to fear the might of American aviation. Yet, amidst this surge of production, something sinister was happening. Crashes were increasing, engines failed, wings snapped, and planes fell from the sky for reasons no one could comprehend.

Beatatrice, a test inspector, was not a loud or famous figure. Her job was straightforward: check planes, sign off on them, and move on. But she possessed a keen eye, one that noticed the tiny gaps, crooked bolts, and mismatched parts that others overlooked. As she ran her pencil along the seams of the planes, she felt something unsettling; the pencil dipped where it shouldn’t have. This small detail ignited a fire within her.

Before the war, America had believed its factories were invulnerable. Bombs had never fallen on New York, and shells had never hit Detroit. But the demand for bombers was staggering, and speed took precedence over quality. Supervisors pushed production quotas relentlessly, and many workers, some of whom had never built anything before, rushed to meet these demands. German spies recognized this vulnerability. Unable to bomb the factories directly, they infiltrated them, posing as workers or bribing those already on the inside. Their plan was simple yet devastating: introduce small, undetectable faults into the planes—loose bolts, shaved braces, thin cracks—enough to cause catastrophic failures at high altitudes.

Initially, the rising number of crashes seemed like a normal consequence of war. Pilots died, equipment failed, and the dangers of combat were accepted as part of the job. But as the numbers continued to climb, even as new planes and skilled pilots were introduced, the situation became alarming. Commanders blamed inadequate training; engineers pointed fingers at material stress and combat fatigue. No one dared to question the integrity of the factory floor. That was unthinkable.

Yet Beatatrice was not convinced. Having grown up fixing things—bicycles, radios, anything broken—she had learned to trust her instincts. During one routine inspection, she ran her pencil across a wing seam and noticed the slight dip. Alarmed, she checked the specifications; the seam should have been flush. She inspected another plane and found the same issue. This pattern continued, and she became obsessed with using her pencil to check every plane she could reach.

Her findings were alarming. The more she inspected, the more she discovered: bolts cut too short, braces filed too thin, fuel lines nicked, rivets loosened just enough to be deadly. She meticulously documented her findings, but when she reported them, her managers laughed. They dismissed her pencil as a tool, insisting it was not in the manual and that she was slowing down production. They ordered her to stop.

But Beatatrice refused. She worked nights and early mornings, checking planes that others rushed past. Her determination only grew stronger, and she kept track of every dip and flaw in a notebook she carried everywhere. Then came the crash that changed everything. A bomber went down during a routine test flight over Long Island Sound, killing both pilots instantly. Engineers discovered a failed wing brace, deliberately weakened just as Beatatrice had marked weeks before.

The implications were staggering. Eighteen planes showed signs of the same damage, all built on the same production lines, all having passed standard inspections, and all ready to fly to Europe. If they had gone overseas, they would have failed in combat, leading to the loss of countless lives. The Army launched a quiet investigation, and counterintelligence moved in, uncovering a web of sabotage that included workers with strange ties, late-night meetings, and hidden German money.

As the plot unraveled, arrests were made, production lines were shut down, and planes were stripped and rebuilt piece by piece. The pencil test was no longer banned; it became standard procedure. Inspectors were encouraged to trust their instincts, their eyes, and their doubts. One thin line of graphite had accomplished what regulations and meetings could not.

Pilots soon noticed the difference. Crash rates plummeted, confidence soared, and planes returned home damaged but intact. Letters from the front expressed gratitude and trust in the planes and the people who built them. Beatatrice never sought recognition; she remained at her post, training others to slow down, to feel seams with their fingertips, and to listen to the subtle signs their instincts provided.

After the war, many heroic tales were told—of aces and battles, of guns and bombs. Few spoke of the factory floors, and even fewer mentioned Beatatrice Schilling. Yet, pilots remembered her. Some wrote letters, others visited years later, expressing their thanks for their lives, families, and futures.

On that fateful April morning, Beatatrice returned to her spot in the factory. The noise, the smell of oil and metal, and the sense of possibility surrounded her. She drew her pencil line again, and this time it stayed flat—perfect, true. A small smile crept across her face. Her story was now part of something much larger. America had not just won the war with bombs and planes; it had triumphed through the dedication of individuals who cared, who questioned, and who refused to overlook danger for the sake of numbers.

By 1944, American factories produced more planes than all Axis nations combined. Millions of workers, thousands of checks, and countless small acts of diligence and courage made the difference between life and death in the sky. The number that mattered most? Eighteen planes, each carrying ten men. That’s 180 lives saved by one pencil line, one woman, and one refusal to look away.