BIGFOOT DRAGGED HIM INTO THE WOODS — WHAT HE SAW STILL HAUNTS HIM TODAY

Bigfoot Dragged Me Into the Woods — and Let Me Live

The doctors said I was lucky.

That word echoed in my head as I sat under the harsh fluorescent lights of Sonora Regional’s emergency room, my right leg elevated, gauze soaked through with blood in three places. Lucky to survive. Lucky to keep the leg. Lucky to be alive.

They didn’t know what luck really meant.

Dr. Meda asked me—again—what attacked me.

I told him I didn’t see it. That it happened fast. That it was probably a mountain lion. He nodded, wrote it down, and didn’t question me. But I watched the pen move across the chart, and I knew it was wrong. The bite radius was wrong. The spacing of the teeth was wrong. The depth was wrong.

But I didn’t correct him.

Because correcting him would mean telling the truth.

And the truth was worse than dying.

My hands wouldn’t stop shaking—not from blood loss, not from pain—but from the memory of the hand that grabbed me. Not a paw. Not claws. A massive, fur-covered hand with fingers too long, nails too thick, gripping my shoulder and pinning me against solid granite like I weighed nothing.

The smell hit first.

Rot. Musk. Wet fur. Something ancient and wrong that bypassed reason and went straight to the part of my brain that still remembered what it meant to be prey.

Then the teeth.

The bite lasted maybe two seconds. It shook me once, the way a predator shakes something small and breakable. My femur creaked but didn’t snap. Then it dropped me.

It didn’t run.

It stood there breathing for three seconds—long enough for me to know it was choosing.

And then it stepped backward into the trees and vanished.

That was four days ago.

But the story really began weeks earlier, deep in the Stanislaus National Forest, where I worked as a ranger. I knew that land better than most people knew their own neighborhoods. Granite peaks. Alpine meadows. Jeffrey pines that smelled like vanilla in the heat.

I trusted that forest.

That trust was my mistake.

I was checking trail cameras—routine work. Solo. Quiet. Too quiet. No birds. No squirrels. Just wind in the high branches and the feeling that something was watching from just beyond sight.

Then I saw the trees.

Young aspens snapped clean at chest height. Fresh breaks. No claw marks. No storm damage. Something had stood on the trail and broken them deliberately, like a warning. I told myself it was bears, even though bears don’t do that.

The third camera was gone.

Not damaged. Not stolen violently. Removed cleanly, using a quick-release clip that required dexterity—opposable thumbs. I radioed it in, logged it, and kept moving because admitting fear felt more dangerous than ignoring it.

That was the second mistake.

By the time I reached the alpine meadow, the forest felt wrong. Sound didn’t travel correctly. Shadows felt heavier. Then I heard the knock.

Wood on wood.

Not a woodpecker. Not wind. A single, deliberate impact.

Then another.

From a different direction.

I left the area shaken but unharmed. At least, that’s what I told myself—until the footage came back from the lab.

Infrared. Night vision. A figure walking upright into frame. Not a bear. Not a man. Long arms. Massive torso. A gait too balanced, too intentional. It stopped, looked directly at the camera, and reached up.

The hand filled the frame.

Then darkness.

Fish and Wildlife called it “inconclusive.” A bear with unusual behavior. Case closed.

But it wasn’t closed for me.

In November, I went back into that wilderness for a winter assessment. Solo. Snowshoeing. Cold but manageable. Everything normal—until it wasn’t.

Trees started falling. One. Then another. Heavy cracks like gunshots. My radio died. My GPS died. My phone died. All at once. Not from cold. From something else.

The smell came back.

Stronger.

Closer.

Then the scream.

Not human. Not animal. A sound that climbed from a low rumble into something that made my teeth ache. I fired into the air. The scream stopped.

And then it came.

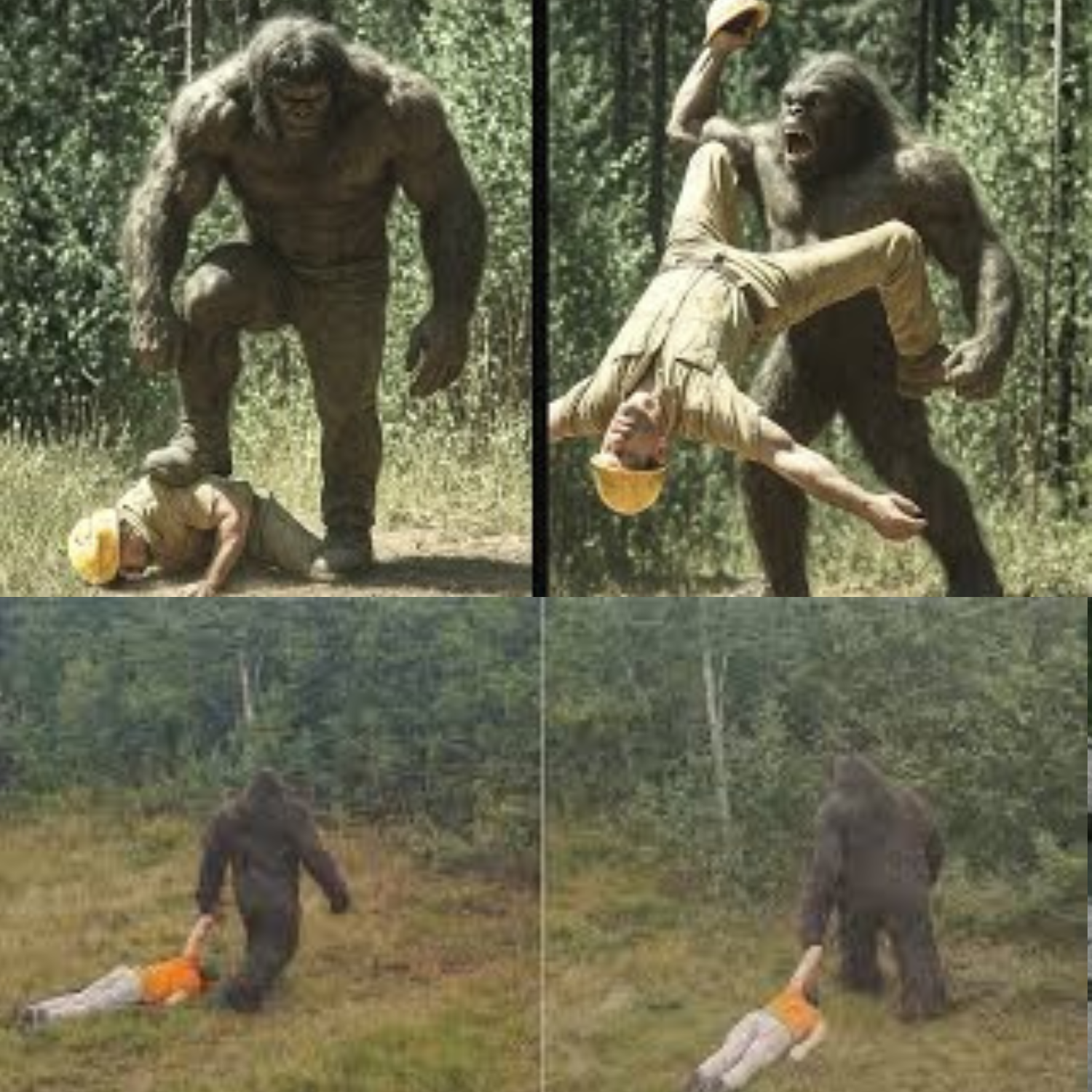

Eight feet tall. Broad shoulders. Dark hair. A face that didn’t belong in any category we understand. I shot it. Center mass. Again. And again.

It didn’t fall.

It screamed and kept coming.

I ran.

I hid.

It tore apart the deadfall like kindling, lifting logs that should have taken three men. When its hand reached into my hiding place, I fired point-blank. It roared—but still didn’t retreat.

It grabbed my ankle and dragged me out.

I ran again, until my leg gave out in a moonlit clearing. That’s where it stood over me, breathing, studying me like a puzzle.

Then it bit me.

Two seconds.

Enough.

It dropped me and walked away.

I bled alone in the snow, crawling for hours until dawn, until a road, until a helicopter. I told the paramedic it was a mountain lion. I told the doctor. I told my supervisor.

Everyone accepted the lie because it was easier.

Now I work a desk job.

I limp when it’s cold.

Sometimes I smell musk where there shouldn’t be any. Sometimes silence feels too heavy. Sometimes I wake up convinced I hear footsteps outside my house.

I know it’s trauma.

I also know what I saw.

I know what grabbed me.

And I know it let me live.

Not because it couldn’t kill me.

Because it chose not to.

And that’s what haunts me the most.

Because something that intelligent…

something that curious…

something that strong…

is still out there.

Watching.

Learning.

Waiting.