The Prescott Brothers — A Post-Mortem Photograph of Buried Alive

“Buried Alive? The Prescott Brothers’ Post-Mortem Nightmare That Will Make You Never Trust a Doctor Again”

Hold onto your tea, folks, because the Victorian era just came back from the grave to slap modern medicine in the face. Picture this: 1858, foggy London streets, top hats, horse manure everywhere—and somewhere in that grimy slice of England, a family tragedy so twisted it would make American Horror Story look like a Disney Channel episode. Enter the Prescott brothers: Herbert, 16, dead—or so everyone thought—and George, 9, standing there like a little angel in a scene straight out of a nightmare. But here’s the kicker: Herbert wasn’t exactly checking out for good. Nope. He was alive. Just… buried. Alive.

Yes, you read that right. Alive. And no, this isn’t some morbid urban legend; this is documented in forensic records, photographs, and letters that make you wonder if Victorian England was just one big episode of Cops: Graveyard Edition.

Let’s back up a sec. Herbert Prescott wasn’t some run-of-the-mill teenager. He was the backbone of his family, filling the dad-shaped void after a tragic carriage accident killed his father three years prior. Mom? Victoria Prescott. Fragile, fragile, fragile. More absent than a Kardashian at a self-help seminar. That left Herbert running the show: cooking, cleaning, working his accounting apprenticeship, basically doing adult-level life at 16. Meanwhile, little George was the kid version of every sweet, helpless character you see in Dickens, except he was about to get the trauma of a lifetime.

On the morning of November 14th, 1858, Herbert woke up looking perfectly normal. Ate breakfast, chatted with George about winter prep—yawn, classic teen routine. Then, later that night, he didn’t come down for dinner. Cue the panic music. George checks on him upstairs and—oh boy—there’s Herbert, lying there in his bed, looking like he just decided to nap forever. Enter Dr. Frederick Hastings, the family physician, who probably thought he was doing the right thing diagnosing “natural death” and recommending a swift burial. Spoiler alert: Dr. Hastings missed one teeny tiny detail: Herbert wasn’t dead.

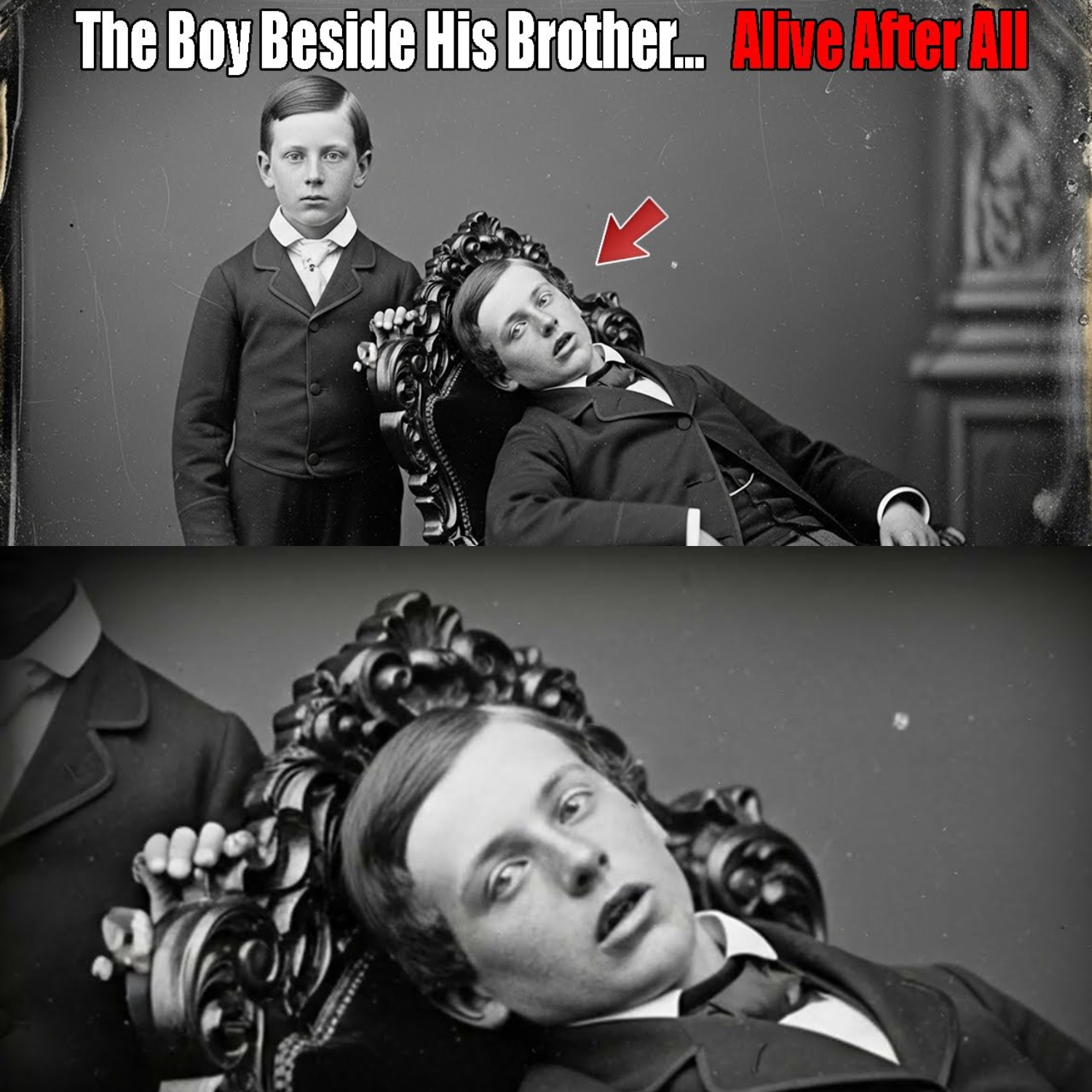

Fast forward one day: enter James Morland, local photographer extraordinaire, carrying the cumbersome equipment needed to capture a Victorian post-mortem photograph. If you’ve never seen one of these, imagine an eerie tableau, stiff smiles, sad eyes, and the occasional ghostly touch of death lingering in the air. Morland positions Herbert in his armchair, George beside him, hand on shoulder—the perfect “goodbye forever” shot. But here’s the thing nobody noticed at the time: Herbert’s face had a suspiciously rosy glow. Could it have been lingering circulation? Or, horror of horrors, actual life?

Decades later, the truth claws its way out of the dirt. 1919, World War I is done, cemetery renovations underway, and enter Dr. Horus Fairchild, a forensic pathologist with a nose for disaster. He pops open Herbert’s coffin—and boom. Nightmare fuel.

The coffin, preserved by magic (or the good kind of soil), reveals Herbert in a position that screams, “I WAS ALIVE IN HERE, PEOPLE!” Arms extended, fingernails scratching at the lid, clothing shredded like some Victorian zombie chic. And get this: skull trauma from the inside. The kid fought for his life after being pronounced dead. Desperation, panic, suffocation, exhaustion—the works.

So, let’s recap because this is the part that makes you want to throw your phone across the room in disbelief: Herbert Prescott was alive when he was buried. Alive. Alive. ALIVE. But the medical geniuses of the 1850s—God bless their hearts—had no idea. Victorian doctors, as competent as they were in bleeding and leeches, had zero tools to detect what we now call catalepsy: a neurological state where you basically become a corpse but your brain is still fully online. Heart barely beating? Check. Breath so shallow it looks like a dying candle? Double check. Consciousness trapped in a coffin? Triple check.

Now let’s talk about the photograph. That iconic, eerie image of George perched beside his supposedly deceased brother? It’s not just a heartbreaker; it’s a forensic goldmine. Experts later noticed subtle signs of life—slightly open eyelids, muscular tension inconsistent with death. Little George, bless his tiny heart, apparently sensed it too, murmuring to Herbert during the photo session as if trying to wake him. Morland thought it was grief-induced imagination. Modern analysts know better. That photo? It’s a silent scream trapped in time, the ultimate proof that Herbert was playing the cruelest prank imaginable: living in what everyone assumed was permanent death.

And here’s the part that really burns you up: Herbert never got a chance to tell anyone. Imagine being 16, trapped in a coffin, fully aware of your impending doom, and unable to scream for help. That’s some nightmare-tier trauma that would scar even the toughest souls. George grows up, carries this haunting image and family legend, probably never sleeping soundly again. And Victorian medicine? Oh, they learned their lesson. Post-1858, premature burial insurance starts popping up like mushrooms after rain. Bells in coffins, ventilation tubes, special contraptions to prevent live burials. People literally paid extra to not die alive. And thanks to Herbert, future generations got slightly better medical protocols. So there’s that silver lining, I guess.

But don’t think this story is all Victorian gloom and morbidity—there’s some deliciously dark irony here. Herbert, the teen responsible and upright, ends up starring in one of the creepiest medical cautionary tales ever documented. He probably died thinking, “I just wanted to survive winter and mind my brother, and THIS is my fate?” And the world? The world plastered a serene, “goodbye” photograph over the screaming reality, probably thinking, “Beautiful, peaceful boy.” Cue the dramatic Victorian piano.

The fallout didn’t just vanish. The Prescott Brothers’ story sparked debates, horror tales, and probably gave Edgar Allan Poe some inspiration for his morbidly fabulous stories about premature burials. Doctors and historians now study Herbert as a prime example of catalepsy, an era’s diagnostic failings, and the brutal reality of misjudged death. Museums display the photograph, showing the world: yes, this was real. No, it’s not a ghost story. Yes, it is horrifying.

Here’s the moral of this Victorian nightmare, folks: never assume life is what it seems. Doctors can be wrong. Loved ones can be unaware. And sometimes, a family photo hides a story so shocking, it makes The Ring look like a bedtime cartoon. Herbert Prescott’s struggle from inside a coffin is a brutal reminder that life—and death—don’t always play by the rules.

So next time you’re mourning, take a moment to appreciate that your relatives probably aren’t clawing at their coffins, fully conscious, wondering why the world’s biggest idiots think they’re dead. And if you see an old post-mortem photo? Look closer. That serene face might just be plotting its next big reveal, decades later, to terrify historians and thrill morbid curiosity enthusiasts like me.

Herbert Prescott: teenager, accidental cataleptic survivor, Victorian horror legend, and the kid who basically wrote the blueprint for coffin bells everywhere. Raise a glass—or a skull—for him, because his story is as terrifying as it is fascinating. And remember, the next time you hear someone say, “He’s dead, I saw it with my own eyes,” check twice. Sometimes, they’re still very much alive, and very, very angry.