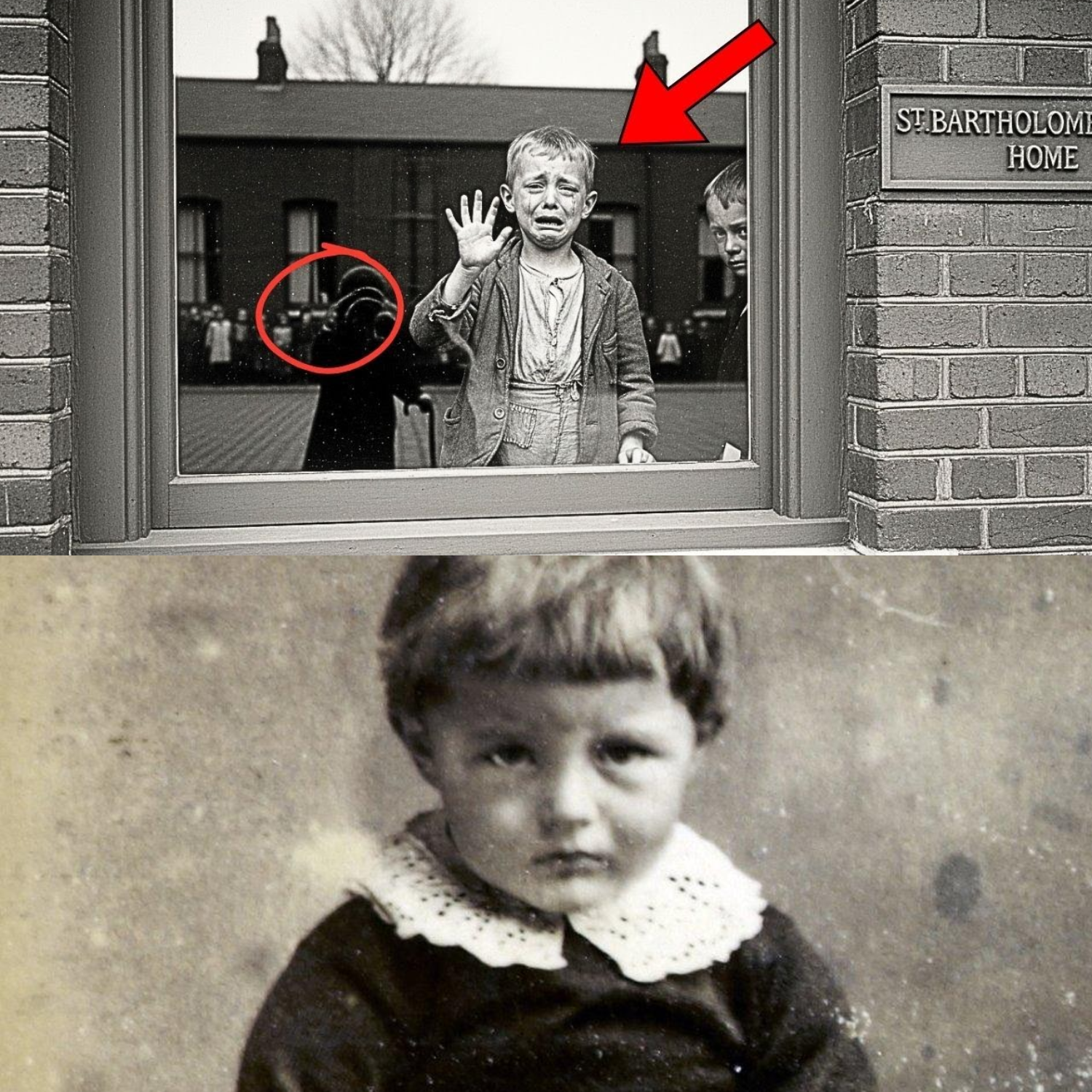

This 1898 Photo of an Orphan Boy Waving Seemed Innocent — Until Restoration Revealed the Truth

In the bitter chill of a London autumn, a small boy stood alone in front of a towering brick building. His coat hung off his frail shoulders like a sail in a storm, trousers rolled up at the ankles, bare feet shivering against the cobblestones. His hair was unevenly cut, his face smudged with dirt, and in his small, trembling hand, he pressed against the cold windowpane. To anyone looking casually, he appeared to be waving, smiling, perhaps greeting a passerby.

For over a century, this photograph was cataloged simply as “Orphan Boy, London, 1898.” The world saw joy where there was none. Historians admired the child’s supposed resilience. Museum visitors believed they glimpsed hope persisting amid hardship. A cheerful wave frozen in time.

But in 2018, Dr. Helena Morrison, a meticulous digital archivist at the British Library, began restoring thousands of Victorian-era photographs. She expected faded smiles and torn edges, not secrets buried for more than a century. When she focused on the image of this boy, something made her pause.

The boy’s lips weren’t smiling. They were pulled back in the grimace of a child holding back tears. His eyes, wide and rimmed red, told a story of anguish that no century-old archive had captured. The hand pressed flat against the window—his “wave”—was not a greeting. It was a desperate attempt to reach someone on the other side. Someone he loved.

Above the entrance, once obscured by decades of wear, the building’s name emerged: St. Bartholomew’s Home for Destitute Children. Founded in 1872, it had promised shelter, education, and safety to London’s abandoned children. In reality, it delivered brutality, neglect, and sorrow. Accounts of canings for minor mistakes, food withheld as punishment, and forced labor surfaced. Dormitories crammed with children, thin blankets in winter, isolation cells in the basement—these were the realities hidden behind the institution’s charitable facade. Over two hundred children had died under its care, victims of disease and neglect.

The boy in the photograph was Thomas Acri, only seven years old. Helena’s research revealed the photograph was taken during a rare visiting day, when parents could briefly see their children. Thomas’s mother, frail and coughing, had come to say goodbye. She was dying. One month later, she would be gone, leaving her son alone in the world.

And Thomas would not stay in London. He was one of thousands of children sent overseas in Britain’s child immigration schemes—euphemistically presented as opportunities, but in truth, indentured labor. He was shipped to Canada, promised a better life, and instead delivered to a farmer named James Whitlock, a man known for his cruelty.

Thomas arrived in rural Ontario in January 1899. Small, malnourished, and frightened, he was immediately put to work: hauling water, feeding animals, cleaning barns. There was no school, no comfort, no one to soothe the quiet, constant ache of a seven-year-old torn from his home. He cried at night, calling for his mother, but there was no reply. When he became sick, no doctor was summoned. He lay feverish in a cold barn, left to survive on his own.

Less than a year later, in November 1899, Thomas collapsed while clearing a field of stones. Whitlock, unwilling to summon help, left him in the barn with only blankets and water. Three days later, Thomas Acri was dead. Eight years old. Alone. Forgotten. Buried in an unmarked grave on the farm, as though he had never existed.

For more than a century, the photograph hung in archives. Generations believed they were seeing hope. They were seeing the truth through a lens polished by ignorance and time. Helena’s restoration shattered that illusion. The boy’s wave was not a symbol of resilience—it was a silent plea. The smile was not joy—it was grief, heartbreak, and the realization that the world had abandoned him.

Thomas’s story did not end in anonymity. One year after Helena’s findings were published, a descendant of the Whitlock family confirmed what she had uncovered. The child’s existence, brief and tragic, had haunted them for generations. The photograph, once thought to celebrate a cheerful orphan, now carried the weight of history’s cruelty.

The image of Thomas Acri is more than a photograph. It is a record of unimaginable loss, of innocence destroyed, of a child forced to say goodbye to the only person who ever loved him. His hand pressed against glass, reaching across time, is a reminder of the tens of thousands of children whose lives were stolen by poverty, neglect, and indifference.

And yet, there is power in remembering. For over 120 years, Thomas’s name was unknown. Today, it is spoken aloud. His story, once lost, now shines through the glass of that photograph. He did not survive, but the world remembers him. The wave he gave to his dying mother, the silent goodbye, has transcended time.

This photograph is no longer about happiness, no longer about resilience. It is about truth. About the pain inflicted by institutions that promised safety but delivered suffering. About a child who loved and lost, who was shipped across an ocean and died far from the only life he had ever known.

Sometimes, photographs do not capture joy. Sometimes, they capture something far more powerful—the unbearable reality of human cruelty, and the memory of a single life that refuses to be forgotten.

Thomas Acri’s hand, pressed against the glass, is no longer invisible. His voice, silenced too soon, finally speaks. And through that photograph, over a century later, he is finally remembered.