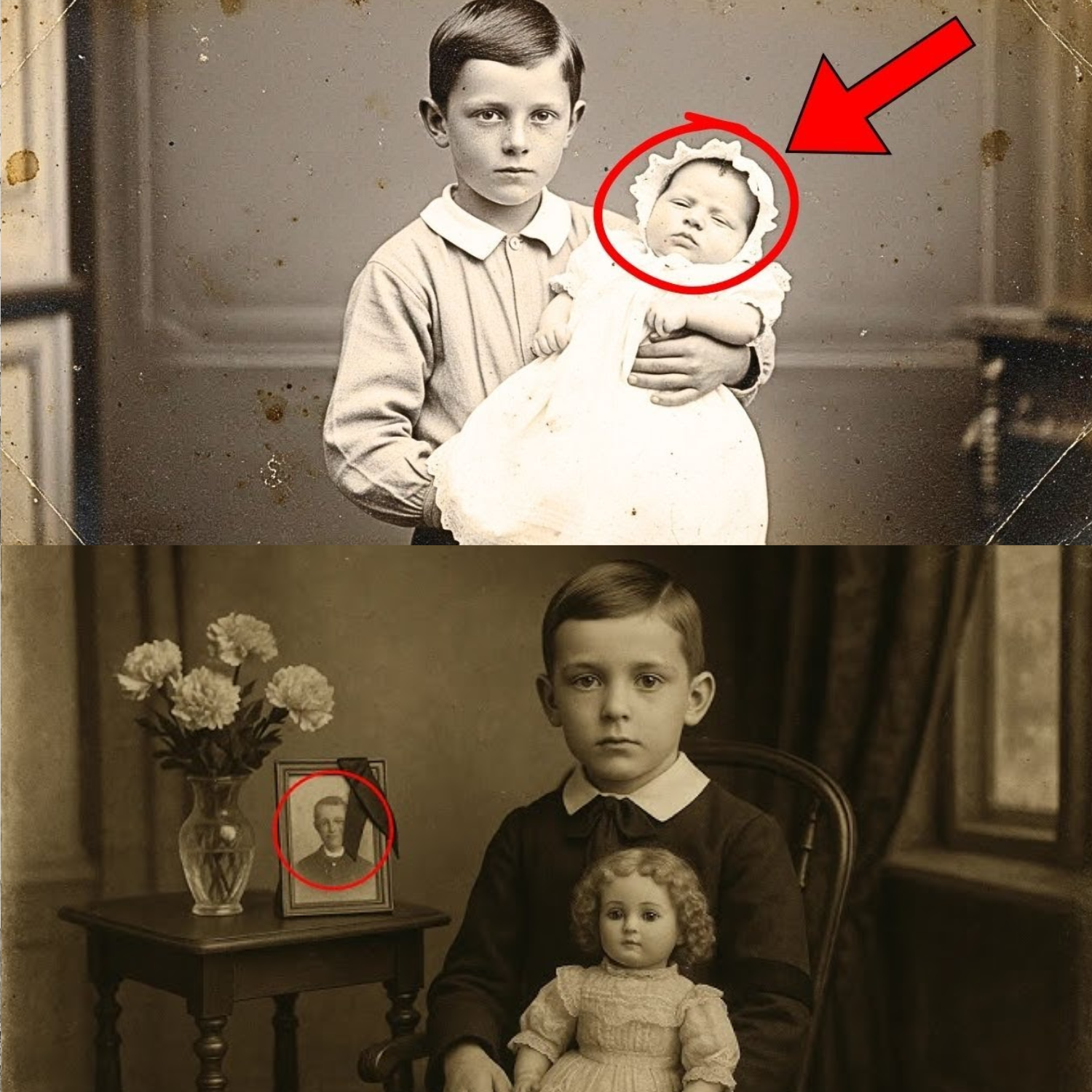

This 1899 Photo of a Boy Holding His Sister Seemed Adorable—Until Restoration Revealed Something Sad

On a quiet June morning in 1899, the parlor of the Morrison family home in Leeds, England, was filled with the delicate hum of anticipation. Eight-year-old Thomas Morrison stood carefully, cradling his six-month-old sister, Emma, in his small but steady arms. Their clothes were freshly pressed, the best the family could afford: Thomas in a new shirt, Emma in a white christening-style gown that Margaret Morrison had painstakingly sewn by hand. It was a special occasion, the first formal photograph of the Morrison siblings, and the family hoped it would capture a moment of innocence, a memory to treasure forever.

The photographer, William Foster, positioned Thomas with tender precision. Thomas, ever the protective older brother, balanced Emma gently, his brow furrowed in concentration. Emma, however, was fussy that day, unsettled and refusing to nurse properly. Margaret, her mother, noticed but attributed it to teething or a cranky spell. Little did anyone realize that this photograph would capture far more than a childhood memory—it would record a silent tragedy, invisible to Victorian eyes yet undeniable to modern science.

Emma Morrison was already dying. Four days later, she would be gone, taken by a disease that no doctor could cure: acute bacterial meningitis. In 1899, meningitis in infants was almost always fatal. No antibiotics, no effective treatments—only helpless observation as the infection ravaged a tiny body, inflaming the brain and spinal membranes until life slipped away.

Margaret’s diary, discovered more than a century later, chronicled the slow, devastating decline. On June 3rd, Emma cried constantly, refusing the breast and burning with fever. The next day, her body stiffened, her tiny head swollen at the fontanelle, a silent alarm that something was terribly wrong. Dr. Harrison visited again on June 5th, confirming what the family could scarcely bear: Emma had meningitis. Prepare yourselves, he said. There was nothing more to be done.

And yet, on June 2nd, that morning when the photograph was taken, Emma’s suffering had already begun. Her small hands were clenched into fists, her body rigid and unyielding in Thomas’s arms. The subtle distress etched across her face—a furrowed brow, tense cheeks, a grimace of discomfort—would go unnoticed for 120 years. Thomas’s own serious expression, so often mistaken for concentration alone, may have been an unconscious awareness that something was wrong.

The Morrison family, like so many in Victorian England, could not have imagined that this innocent-looking photograph was a silent witness to a child’s final days. After Emma’s death on June 6th, the completed photographs arrived. They were displayed proudly, treasured as the last image of the siblings together. Thomas, just eight years old, did not understand why his sister had died. He wandered to her cradle each day, asking why she wouldn’t wake, and stared long hours at the empty space she once occupied. His grief was quiet but profound.

Margaret’s diary reflects the heartbreak with piercing clarity. Thomas blamed himself, wondering if he had held Emma incorrectly, if his care could have changed her fate. Of course, it could not have. Yet that guilt shadowed him for decades, shaping his quiet, serious nature. He left school at 14 to work in the mills alongside his father, growing up under the weight of loss and responsibility. Even when he became a husband and father himself, he rarely spoke of Emma, though he never forgot her.

In 1918, Thomas named his own daughter Emma, a tender homage to the sister he had loved and lost. And though the family continued life as best they could, the truth hidden in that photograph remained unknown, a tragedy frozen in time, invisible to all who gazed upon it.

It was not until 2019, 120 years later, that Dr. Rachel Chen, a pediatric neurologist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals, would reveal the photograph’s hidden story. Using ultra-high resolution imaging, she examined the delicate features of baby Emma: the bulging fontanelle, the rigid neck, the distressed expression, the clenched hands. These were unmistakable signs of acute bacterial meningitis—Emma had been critically ill when the photograph was taken. What had seemed an innocent, endearing image was, in truth, a record of a child clinging to life in her brother’s arms.

Sarah Morrison Davies, a descendant of the family, listened in stunned silence as Dr. Chen explained the findings. For generations, the photograph had been understood as a joyful moment between siblings. Now, it became a testimony of a life ending, a brother’s devotion, and a family’s grief. Thomas had been holding his sister at the very moment she was in the final days of a fatal illness. His careful embrace, his serious expression, and his tender concentration were gestures that carried more weight than any family could have realized.

Emma’s death was a common tragedy of the era. Infant mortality in Leeds during the 1890s was staggering—up to 25% of children did not survive their first year, victims of infectious diseases like meningitis, whooping cough, and measles. Parents lived in constant fear, knowing that the warmth of their nursery could be shattered at any moment by a fever, a cough, a sudden collapse. Photographs, then as now, were precious tokens, a way to preserve a fleeting moment of life.

The photograph, now part of the permanent collection at the Thackray Medical Museum in Leeds, has become more than a historical artifact. It is a testament to the power of modern medical knowledge, revealing what families of the past could not see. It is a memorial to Emma Morrison, who lived only six months, and to Thomas Morrison, who carried the weight of her loss for 68 years. It is a reminder that sometimes what appears sweet in a photograph may conceal profound sorrow.

On a rainy October afternoon in 2019, descendants gathered at Holbeck Cemetery to honor Emma’s memory. Dr. Chen spoke about the disease that claimed her life and the advances in medicine that now save countless infants. Sarah Morrison Davies laid flowers at Emma’s grave, whispering words of love across the century that separated them. The photograph of Thomas holding Emma, once thought simple and charming, now spoke volumes: of a brother’s devotion, a family’s unimaginable loss, and a tragedy that remained hidden until the lens of modern science revealed it.

Emma’s short life, and Thomas’s lifelong love, are now remembered not just in memory, but in understanding. The photograph captures both the tenderness of sibling devotion and the helplessness of a family confronting a child’s death. It shows us that every small gesture of care, every gentle hold, and every look of concern carries meaning beyond what we can see. For Thomas, for Emma, and for generations that followed, that photograph is not merely a relic—it is a testament to love, loss, and the quiet heroism of a boy holding his sister in her final days.

And so, the world finally knows the truth: what seemed a sweet, ordinary Victorian family portrait was, in fact, a witness to an extraordinary act of love—a boy holding his dying sister, unaware he was saying goodbye, captured forever in a single, haunting moment.