Navy Brass Called His Depth Charge Overkill — Until It Surfaced 3 U Boats At Once

The Weapon That Ended the “Blind” Hunt: Hedgehog and the Math of Survival (March 1943)

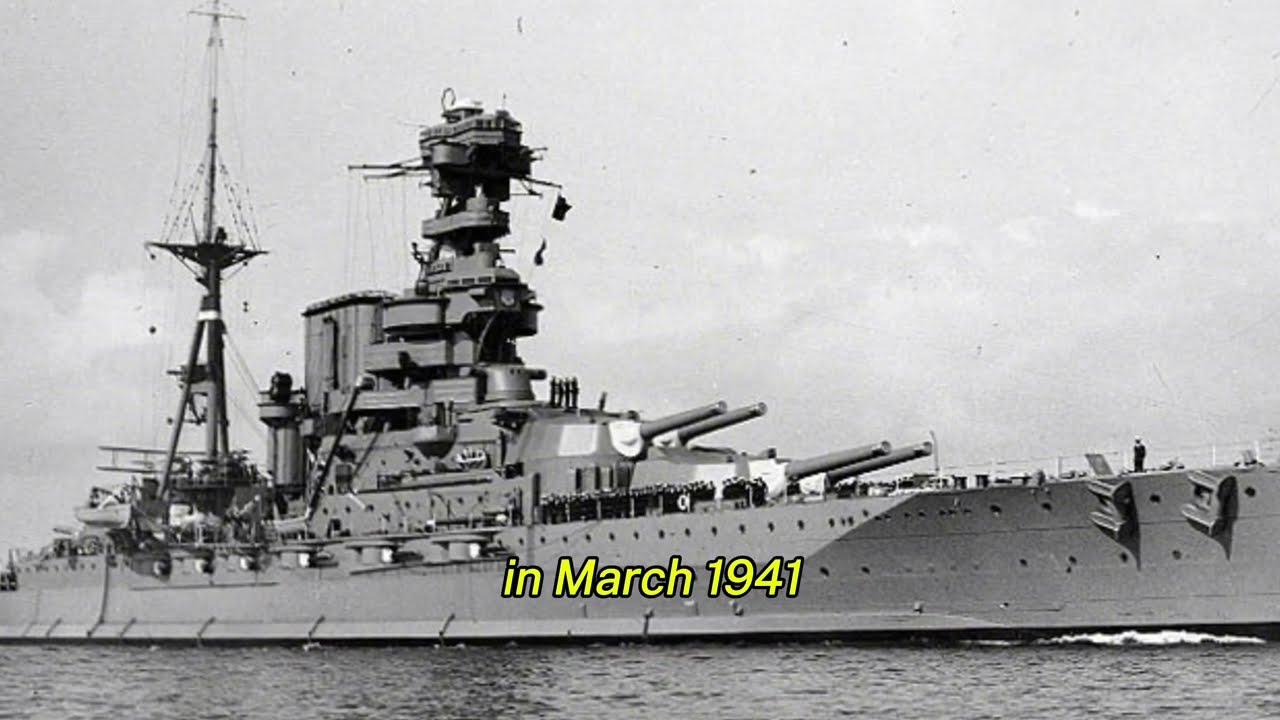

March 1943. The North Atlantic is eating convoys alive.

In a single month, U-boats send hundreds of thousands of tons of Allied shipping down. The numbers don’t feel like “news” anymore; they feel like a countdown. Britain’s entire war effort rides on imported food, fuel, and ammunition—and the ocean is becoming a rationing tool for the enemy.

On the bridge of an escort ship, you can see it: a merchantman burning on the horizon, a black smear of smoke, lifeboats too small for the sea. You can also hear it: sonar contacts sliding in and out like wolves in fog.

And the escorts’ main weapon is a paradox.

The depth-charge trap: the moment you attack, you go blind

Depth charges were the standard anti-submarine weapon for decades because they were simple: a steel can filled with explosive, set to detonate at a chosen depth.

But “simple” wasn’t the same as “effective.”

To kill a submarine, you need a detonation very close to the pressure hull. Yet the moment you drop depth charges, the explosions and turbulence create an acoustic wall—a roaring bubble curtain that makes sonar nearly useless for a critical window right after the attack.

That means the classic pattern looks like this:

-

Detect the submarine (sonar contact).

Run in over the last known position.

Drop a pattern of charges.

Lose sonar in the explosion noise.

Wait… while the submarine moves.

Even if your pre-attack estimate was perfect, the U-boat isn’t a stationary target. It’s moving, diving, turning—often using thermal layers (thermoclines) to bend sound and break contact. In the time you’re deaf, it can be hundreds of yards away.

So the escorts aren’t reliably attacking where the submarine is.

They’re attacking where it was.

And the statistics reflected that ugly truth: huge numbers of attacks, very few kills.

The crisis: arithmetic, not heroics

This is the part that makes the Battle of the Atlantic feel different from land combat. It isn’t mainly about courage (though there was plenty of that). It’s about exchange rates:

How many merchant ships sunk per U-boat sunk?

How fast can shipyards replace losses?

How long until food and fuel reserves collapse?

If the kill rate stays low, Britain doesn’t need to “lose the war” in a dramatic defeat.

It just runs out.

The outsider: a Canadian chemist with the wrong résumé

Into this comes Charles F. Goodeve—a Canadian-born chemist working in Britain’s wartime research ecosystem. He wasn’t a career naval officer, not a ship designer, not part of the Royal Navy’s old boys’ network.

That outsider status mattered, because the problem wasn’t a missing tweak.

The problem was a wrong assumption embedded in doctrine: that you needed massive explosive power and you could accept losing contact during the attack.

Goodeve watched the pattern repeat at sea: approach → drop → go blind → reacquire → find nothing.

He reframed the core question:

What if you could keep sonar contact during the attack?

If the weapon didn’t create a giant acoustic blackout, the escorts could correct aim in real time and re-attack immediately if they missed. That single concept—continuous contact—is the hinge everything swings on.

The idea that looked like a medieval torture rack

Goodeve’s solution was a forward-throwing weapon: Hedgehog.

Instead of rolling big charges off the stern, Hedgehog launched many small bombs forward in a circular/elliptical pattern.

Key design choices (the “why it worked” list):

Forward-thrown: You attack the target ahead of the ship, not after you’ve passed over it.

Contact fuzes: The bombs only explode on impact with the submarine (or very close contact).

No explosion = no sonar blindness: If you miss, the bombs sink silently, and sonar remains usable.

Pattern fire: Multiple projectiles increase the chance one lands close enough to hit.

This is why the Navy initially hated it: the individual warhead looked “too small” compared to a depth charge. But Goodeve’s insight was: if you can put a smaller explosive directly against the hull, you don’t need brute force—you need accuracy.

The doctrinal heresy: accuracy replaces power

Hedgehog didn’t promise a kill every time. It promised something more valuable:

You don’t lose contact when you shoot.

You can fire again immediately.

The submarine gets less warning (no huge pre-attack explosions).

A hit is catastrophic because detonation occurs on the pressure hull.

In practical terms, it flipped the psychology of the fight. With depth charges, the U-boat often knew exactly when it was under attack, then used the chaos to slip away. With Hedgehog, a miss was quiet—so the escort could keep “walking” attacks onto the contact without giving the submarine a free escape window.

“When the hedgehog finally goes to war”

Once installed on escorts and actually used aggressively, Hedgehog’s kill rate was dramatically better than conventional depth-charge patterns in the same era (the exact percentages vary by dataset and time window, but the direction is consistent: multiple times higher).

And that mattered because small percentage changes in ASW kill probability produced huge strategic effects:

fewer convoy losses

fewer experienced U-boat crews surviving to fight again

U-boat commanders becoming more cautious, attacking less boldly

the entire “wolfpack math” shifting against Germany

By mid-1943, the Battle of the Atlantic’s balance turned. Many factors contributed (air cover, radar, HF/DF, escort carriers, codebreaking, improved tactics), but Hedgehog fit perfectly into that turning point because it solved one of the escort force’s most maddening problems:

The attack no longer had to be blind.

The legacy: the principle never went away

Even when Hedgehog itself became obsolete, its core logic survived into later systems:

forward-thrown anti-submarine weapons

rockets/mortars delivering charges ahead of the ship

modern ASW emphasizing continuous tracking and fast re-attack cycles

The enduring lesson isn’t “35 pounds beats 300 pounds.”

It’s this:

In submarine warfare, information is the weapon.

And any weapon that destroys your own information at the moment you need it most is losing you the war.