He Raised a Baby Mermaid in His Home. 10 Years Later, Her Furious Mother Surfaced

.

.

.

He Raised a Baby Mermaid in His Home. 10 Years Later, Her Furious Mother Surfaced

I’m fifty‑two years old, and for the past ten years I’ve been raising something in my home that shouldn’t exist.

Her name is Marina.

At least, that’s what I’ve called her since the night I found her dying on the rocks below my house in October 2014. She is a mermaid. A real one.

Three days ago, her mother surfaced in the cove outside my research station, calling for what I took.

My name is Dr. David Brennan. I’m a marine biologist—or I was, before all of this. I spent fifteen years studying coastal ecosystems along the Pacific Northwest, publishing papers on tidal zone biodiversity, teaching occasionally at Portland State University. I lived alone in a converted lighthouse research station on a remote stretch of the Oregon coast, twelve miles south of Cannon Beach.

After my divorce in 2011, the isolation suited me. I grew used to the rhythm of solitary work: the sound of waves against rock, the predictable cycles of tide and season, the clean routines of data collection.

I need to tell this story now because I’m out of time. Marina is ten. Her mother has been circling my cove for three days, calling to her daughter with sounds that make my windows vibrate.

I have to make a decision that will destroy me no matter what I choose.

I won’t ask you to believe any of this. I’m just going to tell you exactly what happened.

The Night of the Storm

October 17, 2014.

The storm hit the coast around eight p.m., rolling in faster and harder than the weather service predicted. I’d seen dozens of coastal storms in the five years I’d lived at the station. This one felt different.

The wind came in sustained gusts later clocked at over ninety miles per hour. Rain hit the reinforced windows sideways. The ocean turned black and violent, waves throwing white spray up over the cliff in a way I hadn’t seen before.

I was in my main room, half watching the storm, half writing notes on mussel recruitment rates, when the power went out around 10:30. Everything went dark except for the dim glow of the emergency exit signs.

I switched to the backup generator, grabbed my flashlight and rain gear.

Standard procedure during big storms was to check the tide pools at the base of the cliff once conditions were safe. Strong swells sometimes stranded marine life in the upper pools. Over the years I’d found disoriented fish, injured sea stars, even the occasional seal pup.

That night, I didn’t wait.

I’ve replayed that decision a thousand times. Why I went down then, when the wind was still howling and the steps were slick with salt and rain. Whether some part of me sensed what I’d find.

I pulled on my foul‑weather gear, hood up, flashlight in hand, and stepped out into the screaming wind. The wooden stairs bolted into the cliff face shuddered under my boots. Salt spray mixed with rain made it hard to see more than a few feet. I kept one hand on the rope rail as the gusts tried to peel me off the cliff.

By the time I reached the tide pools, I was soaked through.

The pools at the base of the lighthouse formed a series of natural basins carved into the rock over thousands of years. I knew every one of them. I swung my flashlight across the largest basin, expecting to see nothing but churning water and debris.

Instead, the beam landed on something small and pale wedged between two rocks in the shallow end.

My first thought was seal pup. We got them occasionally, separated from their mothers in rough surf. I splashed into the pool, water almost to my knees, the cold biting even through my waders.

The flashlight beam hit its face, and I stopped dead.

It wasn’t a seal.

The face was wrong—too flat in some ways, too defined in others. The eyes were too large and set in a skull that was unmistakably humanoid.

I moved the light down its body.

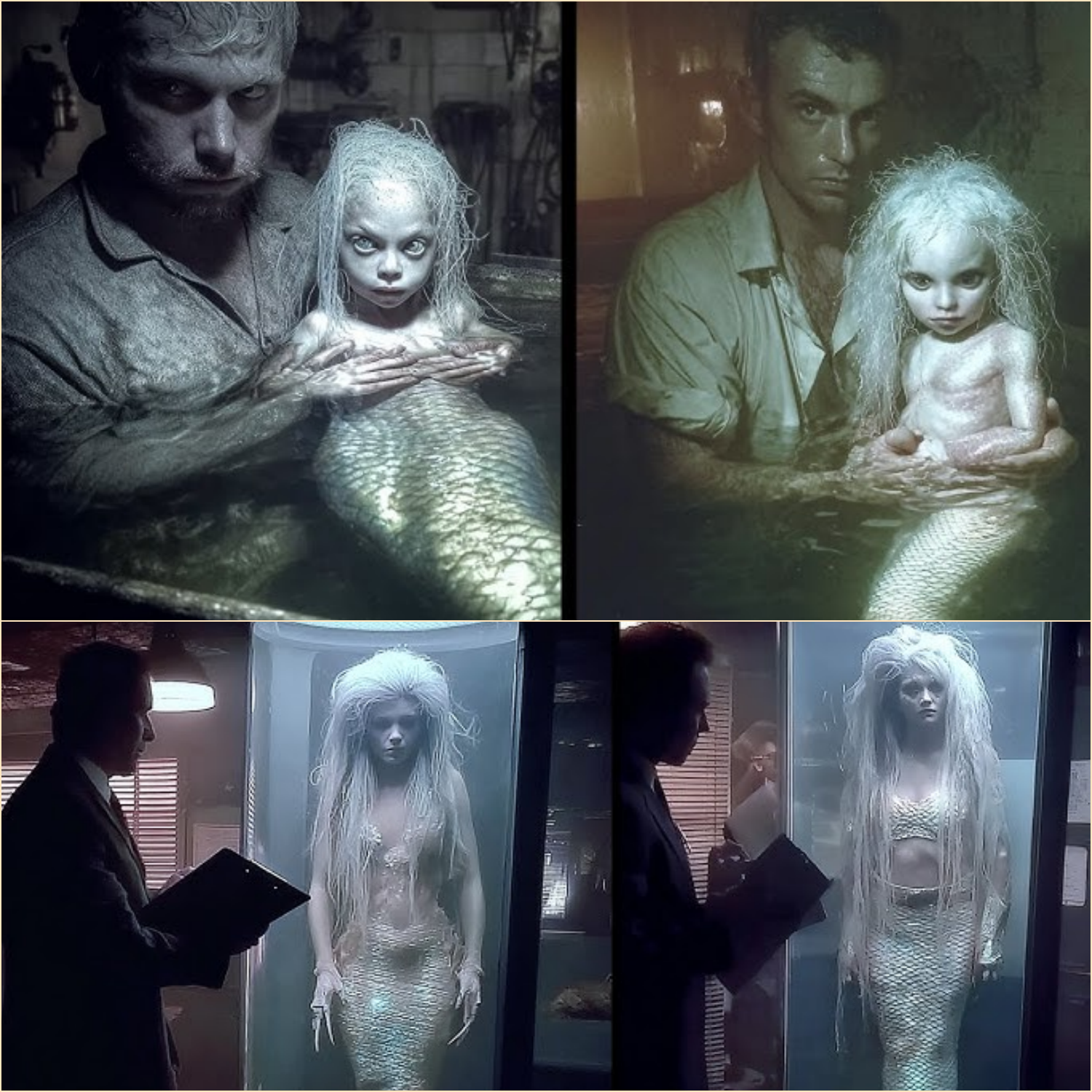

Arms. Hands with five fingers, each finger joined by thin webbing. A torso like a human toddler’s—ribcage, navel, soft belly. And below the waist, where legs should have been, a tail.

Not the soft fin of a seal. A full tail covered in overlapping scales, catching my light in shades of silver and deep blue. Just above the gills at the neck, the skin shivered, trying and failing to pull oxygen from frothing, aerated water.

I stood there in the freezing pool, rain hammering down, staring at something that couldn’t exist.

For several seconds, I thought it was dead. It lay twisted between the rocks, eyes closed, small hands limp. Then I saw the gills on its neck flutter weakly.

It was drowning.

Or whatever the equivalent is when a creature with gills can’t get enough oxygen from boiling water.

I didn’t think. Training, instinct, something older—I still don’t know. I waded forward and reached down.

The creature was maybe eighteen inches from head to tail tip. Lighter than it looked. Its skin felt like a dolphin’s, smooth and cool under my gloved hands. It didn’t respond to my touch. The gill flutters were slowing.

Climbing back up the cliff stairs while cradling the impossible in one arm and my flashlight in the other was one of the hardest physical things I’ve done in my life. The wind shoved at my back, my soaked boots slipped on the steps, and twice I nearly lost my footing. Each time I hugged the small body tighter against my chest.

By the time I reached the top, my arms were shaking from cold and adrenaline.

Inside the station, with the door shut and the storm outside, everything felt suddenly small and quiet. I stood in the entryway, dripping water onto the floor, holding the creature like a child.

Its breathing was shallow, uneven. A long gash ran along its left side, blood mixing with seawater. The tail fin had several deep lacerations.

I had a 200‑gallon saltwater aquarium in my lab for temporary specimens: starfish, anemones, fish I collected and returned. Correct temperature. Correct salinity.

It would have to do.

I carried the creature into the lab and lowered it gently into the tank.

For a long minute, nothing happened. It sank to the bottom and lay there on the sand, motionless. My flashlight beam shook as I watched the gills.

Fifteen seconds between flutters.

Twenty.

I was already thinking ahead—about documenting the body, about who to call, about what this would mean scientifically, politically, existentially—when the gills suddenly began to move faster. The little body twitched. Tiny webbed fingers flexed.

Two enormous eyes snapped open.

They were black at first glance, but when my desk lamp caught them, I saw hints of blue and gray, pupils contracting in the light. The creature looked around the tank and then directly at me.

I know how this sounds, but I’ve spent time around dolphins, sea lions, octopus. There’s a different quality in the gaze of an intelligent animal. This gaze was that—and more. It wasn’t animal curiosity.

It was recognition.

The creature made a sound. Not speech—more a soft series of clicks and whistles, questioning.

“You’re okay,” I said, because it was the only thing that came out. “You’re safe.”

It wasn’t true. Nothing was safe about this.

I spent the rest of the night in that lab.

The power returned a little after midnight, but I kept the generator on as backup. I cleaned and dressed the wounds as best I could with the antiseptics I had, working slowly, murmuring nonsense reassurances. The creature flinched occasionally but did not attempt to bite, scratch, or flee.

By three in the morning, the bleeding had stopped. The gills were moving at a normal, steady rate. The creature floated near the surface now, head breaking the water, watching me with unblinking attention.

I pulled a chair next to the tank and sat.

Outside, the storm raged. Inside, a small, impossible girl—because by then I knew that’s what she was—floated in a tank meant for fish, and my life divided neatly into Before and After.

At one point, when my hand rested on the glass, the girl raised her small, webbed hand and pressed it against the inside of the tank where my palm was.

A deliberate gesture of connection.

That was the moment I realized I couldn’t report her.

Because she wasn’t a specimen.

She was a child.

Keeping the Secret

By dawn, the storm had passed. A gray, wet light seeped into the lab. In the tank, the girl swam slow, tentative circles, testing her strength. The cuts along her side were already trying to close.

I poured coffee and forced myself into scientist mode.

Protocol for an unknown marine species? Document. Photograph. Sample. Inform colleagues. Alert federal agencies. Begin formal research.

But the moment I pictured men in suits, labs, needles, bright lights, the moment I imagined this girl’s life reduced to an endless series of tests and scans, my stomach turned.

At best, she’d become the most studied creature on the planet, her every movement recorded, her tissue biopsied again and again, her behavior analyzed by committees. At worst, she’d vanish into some dark government hole. I may not believe every conspiracy theory I’ve heard, but I know enough about classified research to know that things disappear.

And if there was one, there were others. A population somewhere in the ocean. If I announced her to the world, how long before every navy, fishing fleet, and research vessel started hunting for more?

What happens when humanity discovers an intelligent nonhuman people living in the ocean? We don’t have a great track record with new civilizations.

The girl surfaced at the side of the tank closest to me and made another soft series of clicks and whistles. There was structure to it—repetition, rhythm. Not random noise.

“I don’t understand,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

She tilted her head, eerily human.

That morning, I made a decision that would define the next decade of my life.

I would not report her.

I would keep her here. Hide her. Protect her.

Just for a while, I told myself. Until I understood more. Until I figured out the right thing to do.

I drained my savings on equipment. The basement beneath the station was a concrete, mostly empty space with good drainage—perfect for a custom pool. Over the next two weeks, I built a 1,500‑gallon saltwater habitat with varying depths, heating and filtration, a shallow shelf where she could rest, and a deep section where she could retreat.

I worked at night, bought supplies under the guise of “expanding my research facility.” In a way, it wasn’t a lie.

In those two weeks, I kept her in the lab aquarium. I started calling her Marina halfway through the first week. It was obvious for a marine biologist, almost cliché, but it fit. When I said the name, she seemed to respond more quickly, eyes snapping toward me.

Her wounds healed faster than any mammal I’d seen. Within ten days, the gash along her side had closed entirely, leaving no scar.

She was curious. I’d feel her eyes on me whenever I was in the lab—watching me type, watching my hands when I wrote in my notebook, watching the cursor move on my laptop.

She loved sound.

The first time I turned on the small radio in the lab, she froze, gills flaring, eyes wide. I switched to a classical station by instinct. Strings filled the room. Marina floated motionless, head above water, listening.

Then she made a sound. A soft, high tone that moved with the music. She was trying to match it.

On the fourteenth day, the basement pool was ready.

When I lowered her into it, she swam the perimeter in a single smooth arc, then dove to the deepest point and circled again, exploring. Finally, she surfaced at the shallow end, near where I sat with my legs in the water.

She made a long, rising vocalization that I recognized instantly as pleasure.

She reached out, touched my ankle with her webbed fingers, and dove again.

I had just committed a crime against science, against transparency, against—possibly—my own species. I had also given a trapped, terrified child more space and water than she’d had in weeks.

I told myself I would figure everything else out later.

Raising a Mermaid

The first year was chaos.

There is no handbook for raising a mermaid in your basement. Every decision felt like a coin toss.

Marina was young—about two, I guessed, based on size and coordination. She moved with the uneven grace of a toddler, powerful tail flukes braced by muscles she was still learning to control.

Language came faster than I expected.

She couldn’t produce human speech; her vocal anatomy was different, optimized for underwater communication. But she understood me.

I talked constantly.

It sounds crazy, narrating your life to a child who can’t answer. But I did it: while cleaning, cooking, reading. I named objects. I described actions.

One morning, six months in, I asked, “Are you hungry?”

She nodded.

I froze.

Then tested it. “Are you tired?”

She shook her head.

“Do you want to play?”

Nod.

From there, we built a system. Yes: nod. No: shake. I added basic sign language—modified for her webbed fingers. She picked it up with frightening speed.

Food. Water. Play. Sleep. Friend.

She loved that last sign. Whenever I came down the stairs, she’d surface, sign friend, then produce a series of happy chirps.

Her own vocalizations formed a language I couldn’t hope to master but could partially decode. Short clicks for contentment. Higher whistles for wanting something. Long, low tones when something hurt or frightened her.

Her tail grew stronger. By the end of the first year she had gained six inches in length and could launch herself nearly completely out of the water. More than once, I came down to find objects knocked off shelves from her “jumping practice.”

Feeding her became a full‑time job. She was omnivorous: fish, shrimp, seaweed, kelp, a variety of mollusks. I experimented with market seafood and things I collected from the tide pools. Some she liked. Some she rejected with a face not unlike a disgusted child.

Human food fascinated her, but her system couldn’t tolerate most of it. Bread gave her digestive issues. Dairy was a disaster. I learned the hard way and went back to raw fish and marine plants.

I kept my position at the university. I published two papers on coastal biodiversity and did my best to act normal. My colleagues noticed I was less social, that I rushed home after classes. I muttered something about a long‑term project. It wasn’t entirely a lie.

Every night, after lectures and lab work, after writing emails and pretending everything was typical, I went downstairs and sat by the pool, reading to a mermaid.

I bought waterproof children’s books—cartoon fish, basic shapes. Marina devoured them. She’d press them against the pool wall, eyes inches from the page, tracing pictures with her fingers. I graduated to simple storybooks, lamination and plastic bags to protect them.

By two years in, she could recognize a handful of written English words. She’d point, then sign. Fish. Water. David.

And she drew.

I gave her thick crayons that could mark on plastic. At first, it was scribbles and swirling patterns. Then, slowly, shapes emerged: waves, fish, rocks. One day she held up a sheet depicting a woman’s face, unmistakably a version of herself but older.

I pointed. “Who is that?”

She touched her chest—feeling—then signed mother.

I didn’t ask more that day.

The Double Life

By 2019, Marina was five.

I marked the anniversary of finding her with what passed for a birthday party: a cylinder of compressed fish and seaweed, shaped roughly like a cake, with a single candle I lit and held above the water. She laughed—high whistles and chittering sounds—when I tried to sing.

She was nearly four feet long now, her tail thick with muscle. Scales glinted strangely in the lab lights, colors shifting from deep blues to pale greens depending on angle. Her face had lost its infant softness. Cheekbones, jawline, an expression that could be shy, mischievous, or serious depending on the moment.

Her eyes were extraordinary. In shadow, they were dark, almost black. In direct light, they were a storm‑gray with flecks of blue. They never stopped observing.

Her favorite book was, inevitably, The Little Mermaid.

I hesitated before reading it. A mermaid who longs to leave the sea, who trades her tail for legs? Was that cruel? Manipulative?

Marina insisted, pressing the book into my hands.

She listened without moving through the entire original Hans Christian Andersen version, not the sanitized cartoon. When I finished, she sat very still, then signed sad, beautiful, and touched her chest.

“Do you wish you could walk?” I asked carefully.

She considered. Then signed no, followed by ocean and home, but her hands moved uncertainly.

The problem wasn’t as simple as sea vs. land.

She had an endless appetite for information. I brought down my laptop and showed her videos: reef ecosystems, documentaries about whales, ROV footage from deep‑sea research platforms. She watched, entranced. When dolphins appeared, she chirped excitedly and tried to mimic their sounds, coming closer than seemed possible.

She helped with my work.

I’d bring photos of fish species and ask her to classify them. She would spot subtle differences I had missed—fin shapes, scale patterns. Her intuitive grasp of marine behavior was better than most graduate students I’d trained.

I thought, more than once, that if she had been human, she would have been a brilliant scientist.

But she wasn’t human. And she was growing up in my basement, cut off from whatever culture and community her own people had.

There were days she was purely happy—chattering, drawing, splashing, demanding stories. There were other days she lurked at the bottom of the pool, ignoring my calls, emitting low, sad tones that vibrated in my chest.

She stared often at the narrow basement window near the ceiling, the one that faced the ocean. If I opened it, she would drift just below the surface of her pool, gills flaring, drinking in the scent of salt air, eyes distant.

I started to realize that safety and happiness were not the same thing.

I had saved her life.

I had also given her a cage.

The Longing

When Marina turned eight, something changed.

It was gradual at first—easy to chalk up to a bad week, a growth spurt, some developmental phase. She ate less. Spent longer in the deepest part of the pool. Answered my questions more slowly.

The art changed. She stopped drawing varied scenes and fixated on one thing: the view from the basement window.

Over and over, she drew that small rectangle of world—the line of horizon, the strip of ocean, the faint outline of distant swells—in different lights and weathers. Dawn. Midday. Storm. Calm. Sometimes she taped the drawings to the pool wall and floated near them, staring for long stretches.

Her vocalizations shifted too. At night, when she thought I was asleep, she produced long, deep calls unlike any I’d recorded before. They were powerful enough to make the water in her pool ripple.

I recorded them and ran spectrograms.

They looked like long‑range communication signals, akin to dolphin or whale calls used to contact pod members across distances.

She wasn’t just singing.

She was calling.

For someone.

One December evening, I brought down the tablet and showed her a montage of deep‑sea footage: hydrothermal vents, submarine canyons, open blue water far from shore. When I played a particular clip from Monterey Bay’s deep‑sea cameras, her entire body went still.

She moved closer to the screen, eyes tracking something I couldn’t see—rock formations, perhaps, or the slope of the seafloor. Her gills fluttered rapidly. Then she made a sound—loud and piercing, urgent.

She signed home, tapped the screen repeatedly, then signed mother.

“You remember your mother?” I asked.

She signed yes and no at the same time, a gesture she’d invented for incomplete memory. She touched her head, then traced a rough circle in the water—deep.

Her past was a set of blurry impressions: a sense of depth, temperature, sound. The feel of water far darker and colder than her pool. The presence of another like her.

Her mother.

From that night on, the calls intensified.

I could hear them faintly even from my bedroom: Marina’s cries reverberating through the concrete and water, reaching for something out beyond the shore. She spent hours at the deep end of the pool, eyes closed, body still, gills working steadily as she sent her voice upward and outward.

No one answered.

I burned with guilt.

I had taken her in at two years old. Kept her hidden. Kept the existence of her entire people a secret. For eight years, while her mother searched, I’d been the barrier between them.

I began reading everything I could find—old fishermen’s tales, cryptozoological reports, ship logs. Ninety‑nine percent were nonsense or misidentifications. But a few accounts along the Pacific coast mentioned things that fit: glimpses of humanoid forms at night, strange songs at sea that couldn’t be attributed to known whales.

If there were others, they were very good at avoiding us.

On Christmas Eve, I sat by the pool with Marina. She floated on her back, eyes on the laptop screen as I replayed that deep‑sea footage. When the camera panned over a particular slope, she straightened, tapped the glass, and signed home again.

I turned off the tablet.

“I don’t know how to find them,” I said quietly. “I don’t know how to find her.”

She signed feeling, then understand, then friend.

She wasn’t blaming me. That made it worse.

That night, lying awake listening to her call, I accepted a truth I’d been avoiding: I could not be enough for Marina.

She needed more than a solitary human father and a basement pool. She needed family. Culture. An ocean.

I started planning to let her go.

The Call From the Sea

The ocean didn’t wait for my plan.

On January 19, 2023, just after three in the morning, I woke in a panic.

For a second I thought earthquake—the windows rattled, the water glass on my nightstand rippled in concentric circles. But the shaking came in steady pulses, not the random roll of tectonic plates.

A sound, deep and low, thrummed through the house.

I swung my legs out of bed. The sound came again, louder. A drawn‑out note that vibrated in my chest, not so much heard as felt. It came from outside—from the cove.

I grabbed my flashlight and ran downstairs.

Marina was a blur of silver in the water, tearing back and forth across the pool, emitting frantic calls. When she saw me, she launched herself halfway out of the water and flung a cascade of spray onto the floor.

She signed so fast her hands blurred: mother, mother, mother.

The deep call sounded again, closer this time. A different pitch than Marina’s. Older. Stronger. It lasted fifteen seconds and cut off.

Through the tiny basement window, above Marina’s pool, I saw movement.

Something large surfaced offshore, beyond the rocks at the base of the cliff. Moonlight caught scales and iridescence that hurt to look at, colors that seemed to exist somewhere between blue and green and silver.

A head emerged. Shoulders. A torso.

Larger than Marina by a factor of two. Maybe more.

The figure rose impossibly far out of the water, supported by a tail that stayed submerged. Dark hair clung to its shoulders. Even at this distance, I recognized the body plan: upper half humanoid, lower half tail.

It floated there, scanning the cliffs.

Then it called.

From inside the house, the sound made my teeth ache.

It was the same structure as Marina’s long‑range calls—similar harmonics, similar duration—but older. Deeper. Carried fury and fear I didn’t need a translation for.

I ran outside and down the cliff stairs.

By the time I reached the beach, the creature had moved closer, hovering maybe two hundred yards offshore. In the moonlight, I could see enough detail to know that every assumption I’d made was right.

She looked like Marina.

Older. Bigger. Stronger. But their faces shared lines in the cheekbones, the tilt of the eyes, the shape of the mouth.

Marina’s mother.

She raised herself higher out of the water, eyes fixed on the cliffs, and called again. The sound was a demand.

Give her back.

Behind and below me, in the basement, Marina answered with a cry that shivered the cliff.

The ocean might be wide, but that night, in that cove, it felt like a small, enclosed room in which a family argument about to happen.

The Mother

At dawn, she was still there.

I watched from the living room with binoculars as the gray light grew. She’d moved closer during the night—to within fifty yards of the rocks. She floated just beyond the break, rising and falling with the swell, watching my house.

Up close in daylight, she was breathtaking and terrifying.

Her upper body was built like an Olympic swimmer’s: long arms corded with muscle, broad shoulders tapering to a strong torso. Her tail, thick and powerful, ended in fin lobes longer than I was tall. Scales along her sides shifted color as the light changed, like a school of fish compressed into one body.

Her face could have been human if you squinted, but the proportions were subtly wrong. Eyes a little too large. Pupils adapted to low light. Cheekbones sharper. Mouth wider.

She looked, unquestionably, like Marina’s mother.

I went down to the basement.

Marina was plastered against the pool wall nearest the ocean, eyes glued to the window, making soft, continuous sounds. When she saw me, she turned and signed mother, here, please, ocean.

“I know,” I said. My throat was tight. “I know she’s here.”

She signed go—a strong, urgent motion.

“Not yet,” I said. “We need to think. We need to be careful.”

She made a noise that, ten years in, I recognized as her version of a shout. Frustration, pain, and accusation all wrapped in one rising tone. Then she dove to the bottom and ignored me.

I went outside alone.

The wind had calmed. The surf still pounded the rocks, but the storm flavor was gone. When I reached the wet sand, her head swiveled toward me.

I stopped at the high tide line, hands visible, heart hammering.

“I know you probably can’t understand me,” I called. “But I’m going to talk anyway.”

She stared. The eyes were worse up close—intense, assessing.

“I found her in a storm eight years ago,” I said. “She was dying in the tide pools. I took her in. I kept her alive. I raised her.”

The mother’s face didn’t change. If anything, her gaze sharpened.

“She’s safe,” I added quickly. “She’s healthy. She’s… she’s loved.”

A muscle in her jaw moved. She made a sound—short, clipped. Questioning. Demanding.

“I didn’t know you existed,” I said. “I didn’t know where you were. I didn’t even know your people were real until I saw her. I was afraid of what humans would do if they knew. So I hid her.”

More sound. Sharper this time.

“Tomorrow,” I said. “One day. I need to prepare. I’ll bring her to you. I promise.”

I held up one finger. “One day.”

She tilted her head—a gesture identical to Marina’s—then, slowly, nodded once.

Not human, I thought. But not so different.

She sank below the surface, her tail flipping up once before disappearing. But she didn’t leave. The dark shape moved in the cove, circling, waiting.

The Choice

Back in the basement, Marina was pacing the pool, tail slicing through water with agitation.

“Tomorrow,” I signed and said aloud. “I’ll take you tomorrow.”

She stilled. Her face filled with so much hope it hurt to look at.

Within seconds, it was joined by fear.

We spent the day preparing in ways that had nothing to do with logistics.

I showed her the shell pattern she had made on the shallow shelf: concentric circles of shells and stones around a central rock.

“What does it mean?” I asked.

She pointed at the middle stone and signed home, then at the rings: family, others.

“A map?” I asked. “Of where your people live?”

She signed memory and young. She’d made it from old impressions, not from recent knowledge. Fragments of being carried as a child through deep, cold water.

I pulled up nautical charts of the Pacific on the tablet. We sat by the pool as she traced the coastline with a webbed finger. Her hand hovered over several points, uncertain, then stopped at a section of seafloor sixty miles offshore where the continental shelf plunged.

She tapped it repeatedly.

Maybe. Deep. Home.

I marked it.

“If you go,” I said quietly, “and if you can, remember this place. If anything goes wrong… if you ever want to come back…”

She signed maybe.

We fell into an old routine that felt suddenly final. I brought her favorite foods. She barely ate. I played the cello pieces she loved. She stayed near the surface, eyes half closed, absorbing them.

We went through her drawings. She pointed at one of me—a surprisingly accurate sketch of a bearded man with tired eyes sitting by a pool—and signed friend, father, love.

“I’m not really your father,” I said. “I just found you.”

She signed father again, harder this time.

She wasn’t talking about genetics.

That night, I slept on the basement floor. At some point I woke to find her hand resting on my arm. The sound of the ocean through the window mixed with her quiet, restless clicks.

Neither of us really slept.

Morning came.

I fashioned a makeshift stretcher from a heavy tarp, thick rope tied at the corners. Marina hauled herself onto it with awkward grace. She was heavier now—close to eighty pounds—but I managed.

We made our way down the cliff stairs for the first time together. She kept lifting her head to sniff the air, gills fluttering fast, eyes wide.

At the water’s edge, I lowered the tarp and unrolled it.

Ocean water washed over her tail. She gasped—a sharp, almost painful sound—and then laughed, body shivering with joy.

Her mother was waiting.

When she saw Marina, she made a sound unlike any of the calls before—high, piercing, layered with harmonics that sent a shiver through me. She closed the distance in a few powerful strokes.

They met in waist‑deep water.

For a long moment, they simply looked at each other. Eight years compressed into one look.

Then the mother reached out with trembling hands and touched Marina’s face, her shoulders, her arms, cataloguing every scar, every line, every change. She cupped Marina’s cheeks and pulled her close.

Marina collapsed against her, sobbing in that strange, underwater way—body shaking, vocalizations coming in torn bursts.

I stood knee‑deep in the surf and watched something I had no right to witness: a mother reunited with a child she’d thought dead.

Grief, relief, anger, joy. It was all there.

Eventually the mother released her enough to look around.

Her eyes found me.

If looks could kill, I would have sunk where I stood.

She spoke—if that’s the word—at me. A complex string of tones and overtones that made my bones hum.

Marina unclung herself long enough to sign back toward me.

“She wants to know why you kept me,” she translated with quick, precise movements.

I’d rehearsed this.

“I was afraid,” I said. “Afraid of what would happen to you if other humans found you. I thought I was saving you. I should have tried to bring you to the ocean sooner. I didn’t know how.”

Marina relayed my words. Her mother listened, unblinking.

She replied with another long vocalization, tail agitated under the water.

“She says you did keep me alive,” Marina signed. “She’s grateful. But she says I should have been brought back to the deep. To our people. She says humans always take and keep. They don’t give back.”

Something in my chest cracked.

“I didn’t know your people were real,” I said. “Not until you. I made mistakes. I’m sorry.”

More translation. More sound.

Marina’s face shifted.

“She says humans killed my father,” she signed slowly. “Fishing nets. Metal. Noise. She says our people avoid the surface now. She says humans bring death.”

I thought about what we’ve done to whales, to sharks, to entire fisheries.

I had no defense.

“But she also says…” Marina hesitated. “She says if not for you, I would be dead. She says that matters.”

I nodded, throat too tight for words.

Then Marina signed something I’d been dreading.

“She wants me to go with her. Now. Today. She says I can’t come back here. It’s too dangerous. She says I have to choose.”

The Last Decision

The ocean hissed around our legs. Gulls cried overhead. The world narrowed to three figures at the edge of two worlds.

“What do you want?” I asked Marina.

She looked at her mother.

At me.

Her hands shook as she signed: mother, ocean, home… then father, friend, love.

“I want both,” she signed after a long pause. “But I can’t.”

Her mother watched, understanding more than she pretended. Protective. Impatient.

“Going with her is the right thing,” I said. “For you.”

Marina bit her lip. “I’m scared,” she signed. “I don’t remember them. I only remember you. This house. The pool. Books. Music.”

“You will remember them,” I said. “Your body will remember. Your voice already does. This—” I gestured vaguely at myself, the house, the land “—was never really your world. I just borrowed you from the ocean for a while.”

She touched my hand.

“She says she can’t let me come back,” Marina signed quietly. “Not while humans are like this. She thinks they’ll find us if I keep surfacing. She says… she says this is goodbye.”

It was one thing to know that intellectually. Another to hear it signed by the child you raised.

Marina stared at me.

“I can’t choose,” she signed finally. “Not if I think it hurts you.”

That was the cruelest part.

In order for her to be free, she needed me to free her.

“Of course it will hurt,” I said. My voice cracked. “Losing you will break me. But that’s what being a parent is sometimes. Doing what’s right for your child, even when it destroys you.”

She signed father again.

“I am your father,” I said. “Even if I was never meant to be. And because I am, I’m telling you: go.”

She made a choking sound that turned into a laugh. Then she flung herself at me, arms around my neck, tail wrapping my legs like an anchor.

I held her.

Memorized the weight. The texture of her skin. The faint pulse of her heart against my ribs.

“I love you,” I whispered into wet hair that smelled faintly of salt and something not quite human. “I will always love you. I am so, so proud of you.”

She pulled back, eyes streaming.

She signed love you, thank you, father, and then that new sign again—the one that meant something like you are part of me always.

Then she turned and swam back to her mother.

They spoke—sang—quickly. Marina gestured animatedly, telling her mother everything she could in the little time they had on the surface. Her mother listened with a face made of complicated stone.

Finally, the older mermaid looked at me one last time.

She emitted a long, intricate call that felt like a tide flowing through my chest.

“She says,” Marina translated, “thank you for keeping me alive. She says she can’t forgive everything, but she can forgive that. She says maybe… someday… when your kind are different, our kinds can meet without fear.”

I nodded. It was more grace than we deserved.

Marina lifted one hand and waved—a very human gesture she must have picked up from me.

Then she and her mother turned toward the open Pacific.

They moved in perfect synchronization: two sleek bodies slicing through the water, tails propelling them faster than any dolphin I’d ever watched. In moments they were beyond the break, heading for deeper water.

They surfaced one last time near the mouth of the cove.

At that distance, Marina was just a small shape beside a larger one. But I knew it was her.

She raised her arms in the air and called—a single, clear note that floated back to me across the water. Even without understanding the language, I knew what it meant.

Goodbye.

They dove.

They did not surface again.

After

I stood on the beach until the sun went down, scanning the horizon, listening for a call that didn’t come.

Eventually, the cold forced me back inside.

The basement was the worst.

The pool still hummed with filtration, lights casting soft ripples on the ceiling. Her drawings were stacked neatly on a shelf. Her favorite shells still lay arranged in that pattern—home at the center, family around it.

Everything was exactly as she’d left it.

I couldn’t bring myself to drain the water.

Three days have passed.

The cove is empty. The strange calls have stopped. The ordinary sounds of the coast have returned: waves, gulls, the occasional bark of a distant sea lion.

I keep wandering between floors like a ghost in my own house—bumping into the absence of a presence that defined a decade.

I don’t know if I did the right thing.

I know I saved Marina’s life that stormy night. I also know I stole eight years of what her life was supposed to be. I gave her love, language, stories, and safety. I took her away from her people, from the deep world that shaped her.

I returned her to her mother.

Maybe I did it too late. Maybe I had no other choice. Maybe that’s just how love looks when you are a small, frightened human standing between an impossible child and the ocean.

Somewhere out there—sixty miles offshore, beyond the continental shelf—Marina is swimming in water deep enough to crush steel. She’s learning the full language her calls only hinted at here. She’s discovering her people’s cities, if that’s what those shell maps represented. She’s being told stories of her ancestors. She’s meeting siblings and cousins she doesn’t remember.

She’s home.

I tell myself that over and over when the basement feels too empty and the silence too loud.

She’s home.

I still test the pool water each morning. Check the salinity, temperature, filtration. I know how irrational it sounds, but I can’t bring myself to let it go fallow.

Just in case.

In case storms drive her to the surface again. In case she ever needs a place where she can listen to cello music and read human books in plastic sleeves. In case, one day, she decides to break her mother’s rule and come see what became of the human who raised her.

For now, all I have are memories, field notes no journal will ever publish, and the knowledge that for ten years I was a father to something impossible and beautiful.

She taught me that the ocean still has secrets. That love sometimes means letting go long after you should have.

And that a man with a doctorate in marine biology can stand on a cold Oregon beach, watching the sea, and pray—not to any god he’s ever believed in—but to the water itself:

Please. Let her remember that I loved her.