How Two Brothers Raised a BIGFOOT for 24 Years. What It Did to Protect Them is Unspeakable

THE BOY IN THE DITCH

Chapter 1 — The Ravine That Shouldn’t Have Held a Child

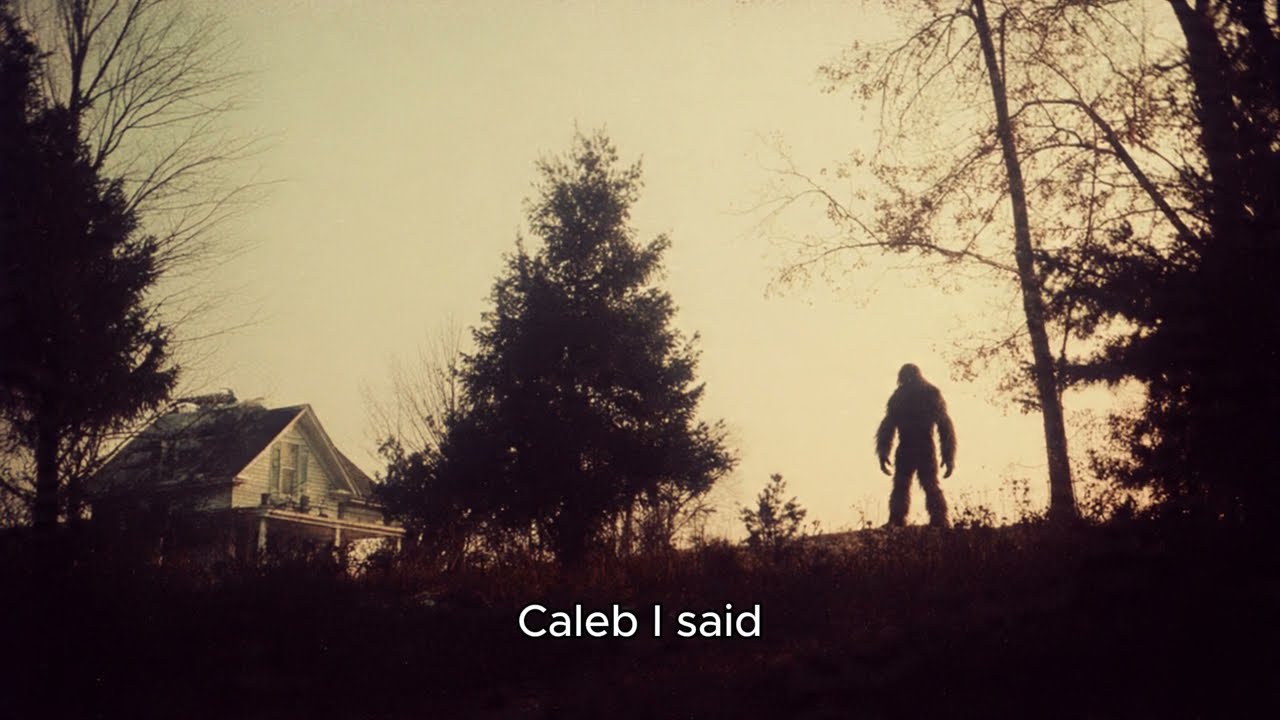

They tell you not to feed the bears. Not to approach wildlife. But no one hands you a rulebook for the day you find a creature that the world insists doesn’t exist—shivering, bleeding, and dying in the mud on your own land. In late October of 1980, after a week of rain so hard the hills looked like they were melting, my little brother Caleb burst through the farmhouse door like he’d been chased by the devil. He was soaked through, mud-caked to the knees, gray in the face, shaking so violently his teeth clicked. He didn’t say “deer” or “calf.” He didn’t even say “animal.” He said, “Silus… I found a baby. It’s hurt. It’s dying. We have to help him.”

.

.

.

Caleb had always been the heart. Our parents were gone—Dad crushed by a tractor, Mom taken by grief six months later—and I’d become the farm, the fences, the bills, the locked door at night. Caleb was the boy who nursed injured birds with an eyedropper, who cried when we had to put down a sick calf, who could walk through a field and make skittish creatures pause instead of flee. We lived deep in Kentucky hill country, three hundred acres backed up to the Daniel Boone National Forest, isolated enough that the radio signal died in the hollows. Looking back, I understand now that our solitude wasn’t just a lifestyle. It was cover. It was the only reason the thing we did next didn’t end in sirens and black trucks by nightfall.

We took the old F-150 down the muddy tractor path and stopped where the land dipped into a limestone gully. A landslide had torn through during the night, exposing raw earth beneath toppled trees. Caleb scrambled down the slope and I followed, sliding more than walking, my boots skidding on wet clay. At the bottom, half buried under a fallen hemlock, lay a shape that made my mind stutter. From a distance it could have been a bear cub—dark, matted, small. Up close it was all wrong. The arms were too long. The legs too straight. And the sound it made wasn’t a growl. It was a cry: a high, warbling keen that hit something human in my chest.

Caleb was already on his knees, trying to lift the branch off it. I froze ten feet away, instincts colliding—every warning I’d ever learned about predators and every unignorable fact my eyes were feeding me. “Get away,” I hissed, because that’s what a sensible man says to a boy kneeling in mud beside unknown teeth. Caleb snapped back, “He’s a baby, Silus. And his mother is dead—look.” Down the slide, under tons of shale, a massive arm jutted lifelessly from the debris. A hand the size of a shovel. The mother had taken the mountain on her back to save the child.

The little creature looked up at me then. That was the moment our lives sealed shut behind us. His face wasn’t gorilla-like, no long snout, no animal bluntness. Flat, dark skin, almost human nose. And eyes—wide-set, amber, intelligent—filled with pure fear. He lifted one long hairy arm toward Caleb, trembling. I looked at the dead mother. I looked at my brother’s pleading face. And I heard myself say the words that would haunt and define me for decades: “Get the tarp.”

We wrapped him. He didn’t fight; he was too cold, too weak. He weighed nearly eighty pounds, dense in a way that made him feel twice as heavy. We carried him up the slope and laid him in the truck bed like contraband. As I drove back to the barn, rain hammering the windshield, I knew two things with bone-deep certainty: we’d just committed a crime no lawbook had a name for, and normal life was over.

Chapter 2 — The Barn Becomes a Secret

We shut the barn doors behind us and the metal track screeched like a warning shot. Under the sickly orange buzz of the overhead lights, we laid him in the folding stall we used for sick animals—the one with a heat lamp. The first thing I noticed when I grabbed his legs was the heat radiating off him, even soaked and shivering, like opening an oven door. The second was the density: muscle and bone packed so tight it felt like iron wrapped in wet hair. Caleb fetched warm water and rags, cleaning mud from the creature’s face with a tenderness that made my stomach knot. I hovered with my hand near the knife on my belt, all nerves and suspicion.

When the creature opened his eyes fully, the air in the stall changed. A bear’s gaze is hunger and instinct. This was something else. He looked at Caleb, then at me, then at the walls, the pitchfork, the latch—assessing, calculating, taking inventory of danger. A low sound vibrated in his chest like stones grinding deep underground. It wasn’t a growl. It was a warning: I am frightened, and I am strong.

Caleb spoke to him in that calm animal voice he used on skittish horses. “You’re safe. We’re not going to hurt you.” He checked limbs, ribs, bruising. No broken bones—just battered, starving, shocked. Then came the first lesson in impossible biology. We mixed calf milk replacer into warm water and brought a giant nursing bottle. The creature sniffed, nostrils flaring, then seized the bottle in both hands and drained a full gallon in under thirty seconds, denting the plastic with his grip. When he finished, he made a soft whistling exhale—a satisfied coo—and leaned his heavy head against Caleb’s knee like a child choosing trust.

That should have been the moment I called someone. A game warden. A sheriff. Anyone official. But I looked at my twelve-year-old brother stroking the head of a living myth, and I could already see the future if I made that call: cages, labs, men who dissect wonders because wonder scares them. Caleb stood between me and the creature as if his small body could stop my decision. “If you call, they’ll kill him,” he said, tears streaming. “Or worse. They’ll keep him alive and ruin him. His mom died saving him, Silus. We can’t throw him away.”

I said yes the way a man signs away his life—quietly, bitterly, aware it can’t be undone. “We keep him,” I told Caleb. “But we have rules. Nobody knows. If he gets aggressive, I end it.” Caleb nodded fast, desperate, as if agreeing would make it safer. That first night I sat in a lawn chair outside the stall with a twelve-gauge across my lap, listening to rain on tin and the creature’s deep breathing. Around three in the morning he sat up and stared at the shotgun for a long time, then pointed at it and pointed at the door. Not fear. Understanding. A question: is that for me, or for what comes for me?

“I’ve got the watch,” I whispered. “Go to sleep.” He lay down. The pact wasn’t spoken. It was felt.

Chapter 3 — Hunger, Noise, and the Mask We Wore

The movies lie about raising something dangerous. They show candy bars and cute mishaps. Reality is louder, smellier, and built on logistics that grind you down until you start to feel like the criminal you’re pretending not to be. Samson—Caleb named him that first week, after the strong man in the Bible—grew like a weed fed on lightning. Five pounds a day. By Christmas he’d doubled in size and could stand eye-to-eye with me, and I’m six-two. Then the hunger changed. One cold January morning he slapped the milk bucket across the stall, roaring in adolescent frustration, shaking the barn hard enough to drop dust from the rafters. Caleb didn’t flinch. He just said the sentence that turned my stomach into ice: “He needs protein. Real protein.”

We couldn’t buy enough meat without drawing attention. A growing creature like him needed fifteen to twenty thousand calories a day. That isn’t groceries; it’s a small business. So we became scavengers. Night after night, from midnight to three, we ran the back roads with a spotlight looking for fresh roadkill—deer, raccoons, possums—anything recent enough that it wasn’t rot. The first time we dragged a whole deer carcass into the barn, Samson didn’t wait for skinning, cooking, or blessing. He ripped it open like a bag and ate with desperate efficiency—meat, organs, marrow—leaving only hooves and skull. The sound of bone snapping and wet flesh tearing is a sound you don’t forget. It taught me the most important truth: we weren’t raising a pet. We were living beside a predator who chose gentleness the way a strong man chooses to hold a baby—carefully, because he can.

Then came the problem of noise. Samson whooped when he was bored, lonely, or simply stretching his lungs—an eerie rising call that rattled farmhouse windows from seventy yards away. If a neighbor heard that, the story would end in search parties. We bought a broken diesel generator from a scrapyard, tore off the muffler, and placed it behind the barn wall. When Samson started vocalizing, we fired it up. To anyone listening, it was machinery—grain dryer, tractor repair. Inside, we blasted bluegrass on an old radio because Caleb discovered Samson loved it. Banjo and fiddle soothed him. He’d sit rocking in straw, humming a low vibrating harmony like a distant engine. Our camouflage became a wall of noise: diesel thunder outside, Bill Monroe at full volume inside.

The closest call came not from sound, but from stink. Summer heat made the barn breathe out a musky, sulfurous odor that didn’t belong to pigs or cattle. One afternoon the sheriff—Deputy Halloway—rolled up unannounced asking about stripped deer carcasses found in the woods. I kept my body between him and the barn, sweating through my shirt while he sniffed the air and frowned. “Jesus, son,” he said. “Something die in there?” I lied without blinking. “Hogs,” I said. “Bad feed. Scour. I’m about to bleach it.” Halloway recoiled, muttered a curse, and drove off.

When I went back inside the barn, Samson stood by a crack in the door watching the cruiser disappear. He looked at me and tapped my shoulder gently, as if to say: you defended the den. That day we stopped being caretakers. We became accomplices.

Chapter 4 — The Bull and the Moment He Became Family

By 1985 Samson was a teenager—eight feet tall, close to five hundred pounds, a wall of muscle and hair with a mind that learned frighteningly fast. We stopped locking the stall because there was no point; he could slide a steel bolt with the delicacy of a watchmaker. He never left without permission, not because he couldn’t, but because Caleb taught him the idea of boundaries. They played a deadly version of hide-and-seek. Caleb would shout “Truck!” and Samson would vanish in seconds, not hiding behind things but becoming the environment—flattening into rafters, slowing his breathing, turning into shadow. We built a small language too: modified signs for three thick fingers and a thumb—food, water, quiet, danger, brother. Samson invented his own: a tap to chest then a point to woods for home, a tap to head and a point to Caleb for smart.

Family games

The day I stopped thinking of him as an experiment happened under a scorching July sun. We had a mean Hereford bull we called Old Ironsides, two thousand pounds of muscle and spite. Caleb and I were fixing fence in his paddock when Ironsides crested a hill and charged. Caleb tripped and went down, ankle twisted, and I ran to put myself between him and the horns because it was the only thing a brother can do when there’s no time left.

Then the world split with a sound like a car hitting a wall. A shadow eclipsed the sun. Samson had cleared the seven-foot fence without touching it and planted himself between us and the bull. He roared—an all-body pressure wave that made my ribs vibrate—and when Ironsides slammed into him, Samson didn’t budge. He grabbed the bull by the horns and twisted, using the animal’s momentum to flip two thousand pounds of beef into the dust. He could have killed it. He didn’t. He let it run.

Then the rage evaporated like steam. Samson dropped to all fours, hurried to Caleb, and touched the swollen ankle with one cautious finger, eyes wide with concern. That wasn’t territorial instinct. That was kinship. Caleb whispered, “I’m okay,” and Samson exhaled a soft coo. He lifted my brother effortlessly and carried him home like a child.

I followed behind them, heart hammering, and realized the most dangerous part of our secret wasn’t his strength. It was his loyalty. Because a loyal monster doesn’t just protect. He avenges.

Chapter 5 — The Mine, the Rut, and the Door Men Shouldn’t Have Opened

By 1990 the barn was too small. Samson was fully grown—nine feet tall, over eight hundred pounds—and spring brought something worse than hunger: the rut. A chemical switch flipped in him, filling the barn with a sharp acrid odor like ammonia and burning rubber, and frustration turned into destruction. One night I woke to a crack-boom that sounded like structural collapse. Samson had splintered reinforced beams like toothpicks, pacing and thumping low in his chest with a vibration that made me nauseous. He spun toward Caleb with dilated eyes and for one breathless second I saw pure animal rage, and my finger tightened on a shotgun trigger as I begged God not to make me kill what my brother loved.

Samson blinked. Recognition returned. Shame followed. He curled into the darkest corner, whimpering like the baby in the ravine. Caleb’s voice shook when he said, “We can’t keep him here. Next time he won’t stop.” He was right. So we moved him at night, three miles through forest under a new moon, to an abandoned coal drift on the far north edge of the property—an old mine we called Copperhead. Underground meant soundproof. Constant temperature. And a heavy blast door we welded onto the entrance more to comfort ourselves than to contain him.

Samson stepped into that mine like a king returning to an older throne. Down there he explored tunnels we never dared, found underground streams, hunted rats and bats, brought us strange gifts: pale cave fish, glowing fungi, oversized insects. But he also grew wilder. Our visits shortened. His dependence shifted from need to choice. The gate wasn’t keeping him in. It was marking where his patience ended.

Then, in 1994, tire tracks appeared on an old logging road near the mine. Cigarette butts. Men scouting the property. I assumed poachers and doubled patrols, but the truth was worse. They weren’t looking for deer. They were looking for a place no one could find.

On a Tuesday evening, three vehicles roared up our driveway—two rusted pickups and a black SUV—blocking the exit. Five men stepped out in tactical vests carrying AR-15s. They grabbed Caleb, pressed a pistol to his temple, and told me the farm belonged to them now. They wanted our land for a grow operation, and they threatened to bury us in “that old mine up on the ridge.”

When they dragged us into the kitchen and tied us back-to-back in chairs, I felt the night change. The crickets stopped. The dog stopped barking. A silence settled so hard it felt like pressure. Then—deep in the floorboards—a low rhythmic vibration began. Thump. Thump. Thump. Samson had woken and found the world wrong.

Chapter 6 — Love Like a Human, Violence Like a God

It started with a massive wet sniff outside the kitchen window. The window was six feet off the ground. Whatever breathed against it was tall enough to look in without effort. The leader—the one with a snake tattoo—raised his rifle and tried to make jokes that tasted like fear. “Bear?” he whispered. “That ain’t no bear,” someone breathed back.

The back doorknob began to turn. Jiggle. Jiggle. Then the oak door exploded inward—not kicked, not shouldered, but punched through. A fist the size of a cinder block smashed wood into splinters. A hand reached through the hole, grabbed a guard by his vest, and yanked him out like a doll. There was a short wet scream and a crunch that turned my stomach. Then nothing.

The room erupted in gunfire. Muzzle flashes strobe-lit the kitchen. Bullets tore into doorframe and drywall, but Samson wasn’t there anymore. He moved like an ambush predator, not a lumbering giant. The kitchen window shattered inward and Samson came through it like a wrecking ball made of hair and fury, landing in the center of the room and rising until his head snapped ceiling fan blades. He roared, and it wasn’t sound so much as force—pressure that rattled cabinets and made teeth ache.

Twitch—the man holding the pistol to Caleb—panicked and fired into Samson’s chest. The bullet struck fur and muscle and did nothing a human mind could accept. Samson crossed ten feet in one step, grabbed Twitch by the face, and swung him into the wall with a sound like a watermelon dropped from a roof. Twitch went limp. Samson tossed him aside and turned those amber eyes on the snake tattoo leader like he was selecting which problem to erase first. The leader tried to reload, hands shaking, and Samson threw the heavy oak kitchen table one-handed, pinning him against the refrigerator with a scream of crushed bone.

One guard fled into the living room and never stood again. Another fell to his knees begging. I thought, foolishly, that surrender might mean something. Then Samson saw the blood on Caleb’s ear from the earlier pistol strike, and something in him locked into a simpler law. He grabbed the kneeling man by the ankles, lifted him upside down, and hurled him through the open doorway into the night like a spear. The remaining screams in the yard lasted two minutes, wet and terrible, then stopped as if the earth itself had swallowed them.

When Samson turned back to us, he was drenched in blood that wasn’t his. His eyes were wild, searching. My fear returned in a rush—because a creature that can do that to strangers can do it to you, too, if the switch doesn’t flip back. He knelt beside Caleb and touched the cut with the gentlest finger, whimpering like a child. He snapped the ropes like sewing thread, freed Caleb, then freed me. The leader, pinned and coughing blood, managed a whisper: “What… what is that thing?” Samson stared at him for a long time, then looked at me and signed one word with brutal clarity: trash.

He dragged the leader into the night. The screams ended quickly.

Then Samson stood at the edge of the woods, looked back once at the house, at the light, at us—and stepped backward into darkness, as if he understood he’d crossed a line he couldn’t uncross.

Chapter 7 — The Cleanup, the Goodbye, the King Who Still Watches

The aftermath wasn’t relief. It was weight. Silence in a room that has heard death isn’t emptiness; it presses on your ears like a hand. We had bodies. We had bullet holes. We had a kitchen that smelled like gunpowder and copper. And we had one sacred objective: nobody could learn what really happened here. Not the cartel. Not the sheriff. Not any agency that would hear “Bigfoot” and translate it into “target.”

We didn’t bury them in shallow soil. We used geology. There was a sinkhole on the far ridge—Devil’s Throat—a vertical drop into an underground river system. We wrapped what was left in heavy plastic sheeting, taped seams to keep fluids from leaking, loaded them into the black SUV like grotesque cargo, and pushed the vehicle over the edge with a tractor. The fall took a long time. The crash echoed up from the earth’s throat, followed by a distant splash. The current down there would drag wreckage into caverns no map can find.

Then we gutted the house. Not scrubbed—gutted. We tore up flooring, cut out drywall, burned wood in a bonfire, mixed diesel fumes with smoke to mask the scent, and rehearsed the story: termites, remodeling, damage. By the third morning, my hands were blistered and chemically burned, and my soul felt peeled raw. Caleb stood on the porch looking toward the trees and asked, “Where is he?” I told him the truth: “Hiding. Because now he knows what he is. And so do we.”

A week later Caleb took a boom box and fresh batteries into a clearing near the mine and played bluegrass into the dusk like a prayer. The woods went quiet. Samson stepped out, thinner, coat matted, eyes clear, stance like a sentry drawing a line. Caleb begged him to come home. Samson looked at my rifle, then pointed at it, then at himself: target—no. Caleb signed family. Samson signed back: me—danger. He motioned toward the house, then made a sweeping gesture: go. He was evicting himself for our safety. Before he left, he tore a branch from an oak, stripped it bare, and planted it in the ground like a boundary marker: do not cross.

He looked at me then, and in his gaze I felt responsibility transfer like a weight placed in my hands. Keep him safe, it said. Because I can’t.

He melted into the woods without a sound.

We lived quietly after that, as if volume alone might summon consequences. We never married. Secrets don’t make good foundations. Years later Caleb got cancer and died with his eyes turned toward the treeline. At his burial, the wind died mid-gust. Silence fell. I looked up to the ridge and saw Samson—gray now, ancient, leaning on a dead tree like the mountain itself had stood up to watch. He raised one open palm. Peace. Then he was gone.

If you’re ever hiking and the forest goes unnaturally quiet, if you smell wet dog and ozone, if you feel watched in a way that isn’t predatory but measured—don’t run. Don’t scream. Don’t shoot. Lower your eyes. Back away with respect.

Somewhere out there is a king who learned love from humans and violence from necessity. And grief has made him patient with almost nothing at all.