7 Terrifying Discoveries In The Amazon That Terrified The World

The Secrets Beneath the Green

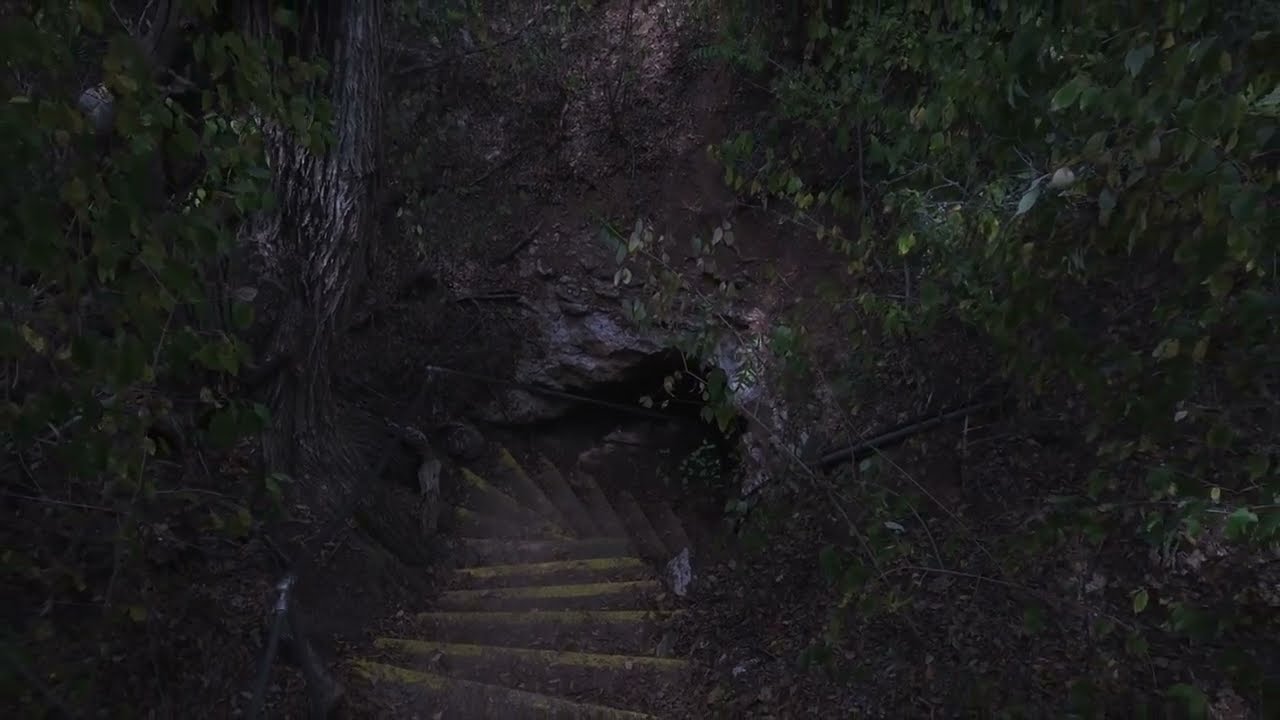

The Amazon rainforest stretches across nine nations like a living secret. Over two million square miles of suffocating green, a place where sunlight becomes a memory on the forest floor. For generations, people told themselves a comforting story: the Amazon was untouched, a wilderness that had always been wild.

But every year, the jungle reveals something that makes us question that story—something that suggests we’ve been walking through the ruins of a world we never knew existed.

I first arrived in the Amazon as a young researcher, eager, naive, and convinced I was entering a place that civilization had never tamed. I believed the textbooks: the forest was too hostile, the soil too poor, the environment too unforgiving for anything but scattered tribes and wandering animals. I thought I knew what wilderness meant. I was wrong.

My first assignment was in Peru, near the banks of a river the locals called the Shaet Tempishka—the boiling river. It flowed through the jungle like a wound, releasing clouds of steam so thick they seemed to erase the world beyond. The water was so hot it could cook flesh in seconds. Locals spoke of Yakumama, the mother of waters, a serpent spirit that breathed heat into the earth. Scientists tried to explain it away—a fault system, geothermal energy—but the truth was, no one really understood. The river boiled, and the jungle kept its reasons.

One morning, I watched a bird lose its way in the mist, dip too low, and vanish. The sound that followed was brief, a hiss and a thud, and then silence. The river didn’t just kill; it prepared its victims, like a meal that no one ordered.

That was my introduction to the Amazon. A place where the rules of the world bent and sometimes broke entirely.

But the river was only the beginning.

In the early 2000s, our team used a technology called LiDAR—light detection and ranging—to scan beneath the canopy. The lasers bounced through gaps in the foliage, mapping the ground below. What we found was impossible: beneath the endless green, hidden under centuries of decay, were cities. Not villages—cities. Networks sprawling across hundreds of square miles, roads connecting them in straight lines, earthwork pyramids rising above the forest floor, reservoirs and canals, ceremonial centers.

It was as if an entire civilization had been swallowed by the jungle. In Bolivia, we uncovered the remains of the Casarabe culture—settlements linked by causeways, platforms for homes, water management systems that controlled rivers and redirected floods. In Ecuador, the Upano Valley revealed garden cities, agricultural terraces carved into hillsides, roads wide enough for processions.

This wasn’t survival. This was mastery. Urban planning on a scale that rivaled ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia. And every year, new sites emerged from the jungle, larger and more complex than the last.

The terror of these discoveries wasn’t just what they were—it was what they told us about what we didn’t know. For centuries, explorers and scientists saw wilderness. They were wrong. The jungle was a graveyard. We walked through ruins every day and never knew.

But these cities weren’t just abandoned. They were erased. So completely erased that we forgot they ever existed. The people who built them, who lived and loved and died in them, vanished. And until LiDAR pierced the canopy, we didn’t even know to look.

If entire civilizations can be swallowed by the jungle and forgotten, what else has been lost? How many societies rose and fell without leaving a trace we could recognize? And if the forest could erase them, what’s stopping it from erasing us?

The colonial powers tried to conquer the Amazon. Spanish and Portuguese forces pushed deep into the jungle, building forts and outposts meant to last forever. But the Amazon doesn’t recognize conquest. The jungle moved in, vines crept over stone walls, trees grew through plazas, soil buried streets. Within a few generations, the outposts were gone—erased from the physical world, existing only in archives and footnotes.

LiDAR found them again: stone foundations, defensive walls, barracks, all buried beneath layers of vegetation. Some of these structures were less than 250 years old. In the span of time since the American Revolution, the jungle erased fortresses built by empires.

What makes this so chilling is the speed. We think of erasure as something that takes millennia, but in the Amazon, it happens in centuries—sometimes less. The jungle doesn’t need a cataclysm. It just needs time and patience.

But not all horrors are buried in the past.

There is a sound in the Amazon that doesn’t belong—the roar of chainsaws, the grind of heavy machinery, the crash of ancient trees. Illegal logging. Satellite images show new roads appearing overnight, thin lines carved into the green, pushing deeper into protected areas and indigenous territories.

For every commercial tree removed, dozens more are damaged or killed. In 2022 alone, the Amazon lost an area of forest larger than Connecticut. The pace is accelerating.

But the ecological catastrophe is only part of the terror. The other part is human. The Amazon is home to over 400 indigenous groups. Some have chosen contact with the outside world. Others have not. These are the uncontacted tribes, living in voluntary isolation for centuries. Now, the logging roads are reaching them. For them, the sound of a chainsaw is an apocalypse.

Reports have surfaced of indigenous people killed for defending their land, entire communities forced to flee deeper into the jungle, only to find that the destruction is following them.

We can track the deforestation in real time. We can see the roads spreading like cracks in glass. And yet, the destruction continues because the money is too good, the forest is too big, and enforcement is too weak.

Scientists speak of a tipping point—the idea that if the Amazon loses too much forest cover, it will transform into a savannah, a dry, open landscape that can never be restored. Some say we’re already close to that threshold.

Lose the Amazon, and the climate crisis accelerates beyond anything we’ve seen.

But the Amazon’s strangeness isn’t just in its ruins or its destruction. It’s in the things that should not exist.

Stories persist—told by indigenous tribes, explorers, scientists—of creatures that don’t fit. The maricoxi: large, bipedal beings covered in reddish hair, walking upright, with ape-like features. The minguari: a giant, hair-covered beast with long claws and an unbearable stench, sometimes described as having a single eye or a mouth in its torso. The rivers hide their own terrors—anacondas said to reach impossible lengths, and the candiru, a parasitic catfish that can lodge itself inside the human body.

Are these legends, misidentifications, or something else? The Amazon is vast and unexplored. In a place so big, possibility is enough to keep people awake at night.

But the deepest mystery isn’t what’s hidden. It’s what used to be there—and where it went.

The people who built the cities, who engineered the soil, who transformed the landscape, are gone. Disease, drought, war—within a century, millions collapsed, vanished, leaving only structures for the jungle to erase.

And here is the most unsettling truth: the Amazon rainforest, the symbol of untouched nature, is not natural at all. It is a garden, a managed system, a living monument to a civilization that has been almost completely forgotten.

The engineered soil—terra preta—is scattered across the basin. The distribution of tree species is not random; useful plants cluster around ancient settlements, suggesting the forest itself was planted. The wild Amazon is not the forest’s natural state. It is what happens when a managed system collapses and runs wild for centuries.

For 500 years, we looked at the Amazon and saw wilderness. We used that image to justify our treatment of it. It doesn’t belong to anyone. It’s not being used. But we were wrong. It did belong to someone. It was being used. We just didn’t recognize it.

We were walking through a garden and calling it wild. Looking at the ruins of a civilization and calling it empty. And now, as we finally begin to understand what the Amazon really is, we’re destroying it faster than ever.

The terror of this discovery is existential. It is the realization that an entire world can end, that millions can vanish, that their knowledge can be lost, and that the rest of us can walk through the ruins without ever knowing they were there.

The Amazon is not a warning from the distant past. It is a mirror. Because if it happened to them, it can happen to us. And maybe, in some way, it already is.

Every year, LiDAR uncovers new sites, new roads, new evidence of the world that was. But the jungle is patient, and there are still places the lasers haven’t reached. What is waiting there? We don’t know. But the Amazon has taught us one thing: the answers are never comfortable. And the deeper we look, the darker they become.