Execution of 27 Nazis who Killed Belgian Women: Hard to Watch

The Courcelles Massacre: Collaboration, Resistance, and Retribution in German-Occupied Belgium

On the evening of August 17, 1944, near the industrial city of Charleroi in German-occupied Belgium, a car carrying Oswald Englebin—a prominent Belgian collaborator aligned with Nazi Germany—was ambushed by resistance fighters. Englebin, his wife, and child were killed in a daring attack that symbolized the growing resolve of the Belgian Resistance as Allied forces pushed north from France and German troops retreated. By dawn, the repercussions of this act would spiral into one of the most infamous atrocities of the Second World War in Belgium: the Courcelles massacre.

Belgium Under Nazi Occupation

The Second World War began on September 1, 1939, with Germany’s invasion of Poland. Within months, Adolf Hitler turned his attention to Western Europe. On May 10, 1940, German forces attacked Belgium, the Netherlands, and France in a coordinated blitzkrieg campaign. The Netherlands fell in weeks, Belgium surrendered on May 28, and France was defeated by late June. Western Europe was now under Hitler’s control, and Belgium faced a harsh German occupation.

The surrender created a power vacuum. King Leopold III remained in Belgium under house arrest, while the government fled to London, forming a government-in-exile. A German military administration established itself in Brussels, ruling alongside the Belgian civil service. The occupation was marked by the systematic dismantling of political freedoms, censorship of the press, and severe restrictions on daily life.

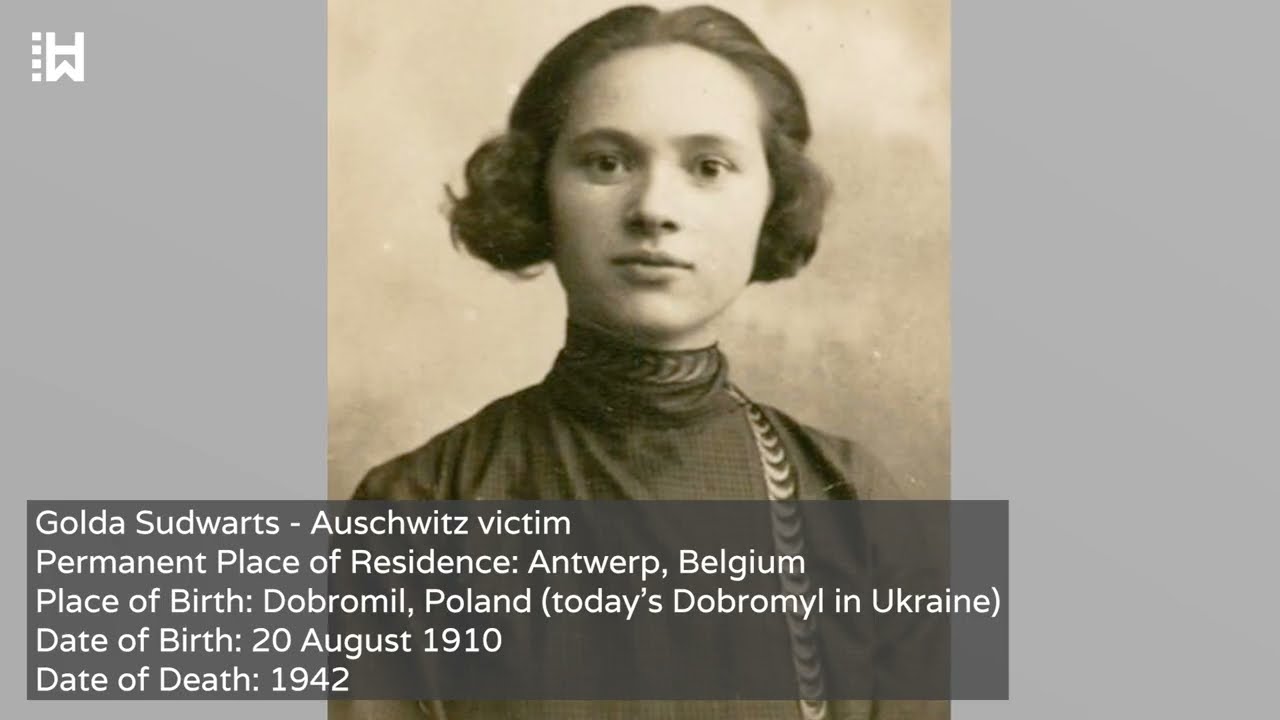

Among those most affected were Belgium’s Jews, numbering between 65,000 and 70,000—many of them immigrants or stateless refugees from Poland who had sought safety after the First World War. Their hopes for refuge quickly evaporated. The German authorities introduced anti-Jewish ordinances, seizing businesses and property, expelling Jews from public life, and gradually isolating them from society.

By mid-1942, deportations to Auschwitz had begun. German authorities used Mechelen and Breendonk as collection centers, sending thousands eastward under false pretenses of resettlement. In reality, deportation meant near-certain death: nearly 25,000 Jews were sent to Auschwitz, with fewer than 2,000 surviving. Families were torn apart, and communities that had thrived in Antwerp and Brussels were almost erased. Yet, with the help of neighbors, priests, and underground networks, more than 25,000 Jews managed to go into hiding. The Belgian civilian administration’s refusal to cooperate with deportation orders frustrated German efforts, but the scale of loss remains one of the darkest chapters of the occupation.

Collaboration and the Rise of Rex

The occupation empowered collaborationist movements, chief among them the Rexist Party, or Rex, founded in 1935 by Léon Degrelle. Before the war, Rex had enjoyed some electoral success, but by the time of the German invasion, its influence had waned. With German support, Rex seized a new chance at power. In January 1941, Degrelle pledged full loyalty to Nazi Germany, and Rex became indispensable to the occupiers, especially in Wallonia—the French-speaking southern half of Belgium—and in Charleroi, where Rex installed its own mayors and paramilitary militias.

On November 19, 1942, Prosper Teughels, the Rexist mayor of Greater Charleroi, was gunned down by resistance fighters, marking a turning point. The occupiers responded with brutality, shooting hostages at Breendonk and tightening repression across the country. Belgium became a nation divided—scarred by antisemitic persecution, threatened by collaborators, and held together only by the growing determination of the Resistance.

Resistance and Reprisals

By 1943, as German defeats mounted on the Eastern Front, the Resistance grew stronger. Rex tightened its grip on Wallonia, expanding its paramilitary units in Charleroi—a working-class city with deep socialist and communist traditions. Rex positioned itself as a bulwark against communism, echoing Nazi propaganda about a crusade against Bolshevism. Léon Degrelle left for the Eastern Front to fight with the Walloon Legion, while Victor Matthys took charge at home. In his New Year’s address of 1944, Matthys promised that Rex would personally avenge every attack on its members, a threat soon followed by violence.

On June 6, 1944, Allied troops landed in Normandy. As the Allies advanced, resistance attacks in Belgium grew bolder. On July 8, Léon Degrelle’s brother Édouard was executed by resistance fighters, triggering bloody reprisals across southern Belgium. Only weeks later, on July 28, Jules Hiernaux, director of the Labour University in Charleroi, was murdered in his home for his ties to the Freemasons—a group the Nazis claimed worked hand in hand with Jews in a supposed global conspiracy.

By the summer of 1944, Belgium was on the edge of crisis. German retreat, resistance attacks, and Rexist vows of revenge created an atmosphere of fear and anticipation. It was in this climate that the events of August would erupt into the Courcelles massacre.

The Courcelles Massacre

On the night of August 17, 1944, more than twenty civilians were dragged to a requisitioned house in Courcelles, near the site where resistance fighters had ambushed and killed Oswald Englebin with his family. The captives, including Father Pierre Harmignie—the dean of Charleroi and a vocal critic of the Nazis—as well as lawyers, engineers, and police officers, were locked in a cellar as their captors prepared their execution.

At dawn, the Rexists started the engines of their vehicles to drown out the sound of gunfire. One by one, the hostages were led outside. Father Harmignie reportedly offered comfort to the others before his death, saying, “I die, and we all die, so that peace may reign in the world, and so that men may love one another.” Each victim was shot in the back of the head, their bodies dumped near the spot where Englebin had fallen. Nineteen were executed this way—the largest group of victims in the massacre.

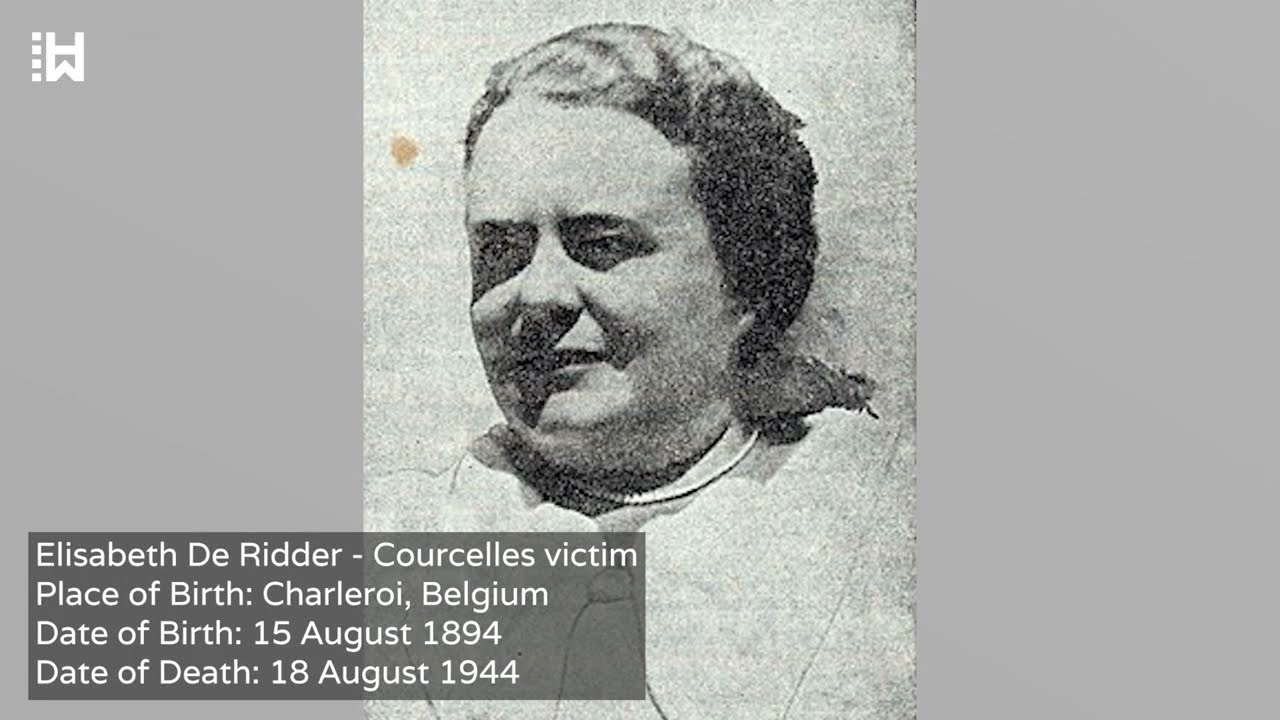

The killings continued. Later that day, Germaine Van Hoegaerden-Dewandre, president of the Charleroi Red Cross, was shot with three bullets to the back. Elisabeth De Ridder, housekeeper of a local architect, was also murdered. In total, twenty-seven civilians were killed in Courcelles between August 17 and 18, 1944.

Amid the slaughter, two prisoners survived: Marcel Stoquart was released before the transfer, and Germaine Gobbe was spared when a Rexist cousin recognized her. For the rest, no mercy was shown.

Propaganda and Terror

The massacre at Courcelles was not ignored by the occupiers. German authorities tolerated and even used the killings for propaganda, declaring that Englebin and his family had been murdered by “terrorists” and claiming that twenty resistance fighters had been shot in reprisal. In reality, the victims in Courcelles were innocent civilians, chosen to spread fear and strengthen collaborationist control. Separately, the Germans carried out their own reprisal, executing twenty hostages for earlier resistance actions.

Both the collaborationists and Nazis used terror as a weapon of control, a brutal reminder of the cost of occupation.

Justice and Memory

Allied forces liberated Belgium in September 1944, but the memory of the massacre was still fresh. The pursuit of collaborators began almost immediately. Belgian authorities launched investigations into the events at Courcelles. Out of around 150 suspected participants, 97 were identified; 80 were captured and put on trial.

On November 10, 1947, justice was carried out in Charleroi. Twenty-seven Rexists were executed by firing squad, including leading figures such as Victor Matthys and Louis Collard. Joseph Pévenasse, the regional leader and lawyer, also faced trial for organizing the killings.

In the years that followed, memorials to the victims were built across the region. Saint-Christophe Church in Charleroi was rebuilt and dedicated in December 1957, with a memorial honoring Father Harmignie and others who died. In Courcelles itself, a monument was erected at the site where the bodies were found, and nearby streets were renamed in memory of the victims. Each year on August 18, ceremonies commemorate the massacre.

Legacy of the Courcelles Massacre

The Courcelles massacre remains one of the most infamous examples of collaborationist violence in Belgium during the Second World War. It exposed the deadly extremes of betrayal, ideology, and revenge in a country already scarred by occupation, repression, and the Holocaust.

The massacre stands as a stark reminder of the dangers of collaboration with oppressive regimes and the brutality unleashed when ideology trumps humanity. The events at Courcelles were not isolated; they were part of a broader pattern of violence and terror that marked the Nazi occupation of Belgium. The courage of the Resistance, the suffering of the victims, and the eventual pursuit of justice are threads that run through the tapestry of Belgian history in the twentieth century.

As Belgium rebuilt in the aftermath of the war, the memory of Courcelles helped shape national consciousness about the importance of resistance, the dangers of collaboration, and the need to remember those who suffered under tyranny. The annual commemorations, memorials, and historical accounts ensure that the lessons of the massacre remain alive for future generations.

Conclusion

The Courcelles massacre is more than a tragic episode in Belgian history—it is a symbol of the struggle between oppression and resistance, of the cost of collaboration, and of the enduring need for justice and remembrance. As time passes, the stories of those who died in Courcelles continue to resonate, reminding us that even in the darkest moments, the pursuit of peace, dignity, and humanity must never be abandoned.