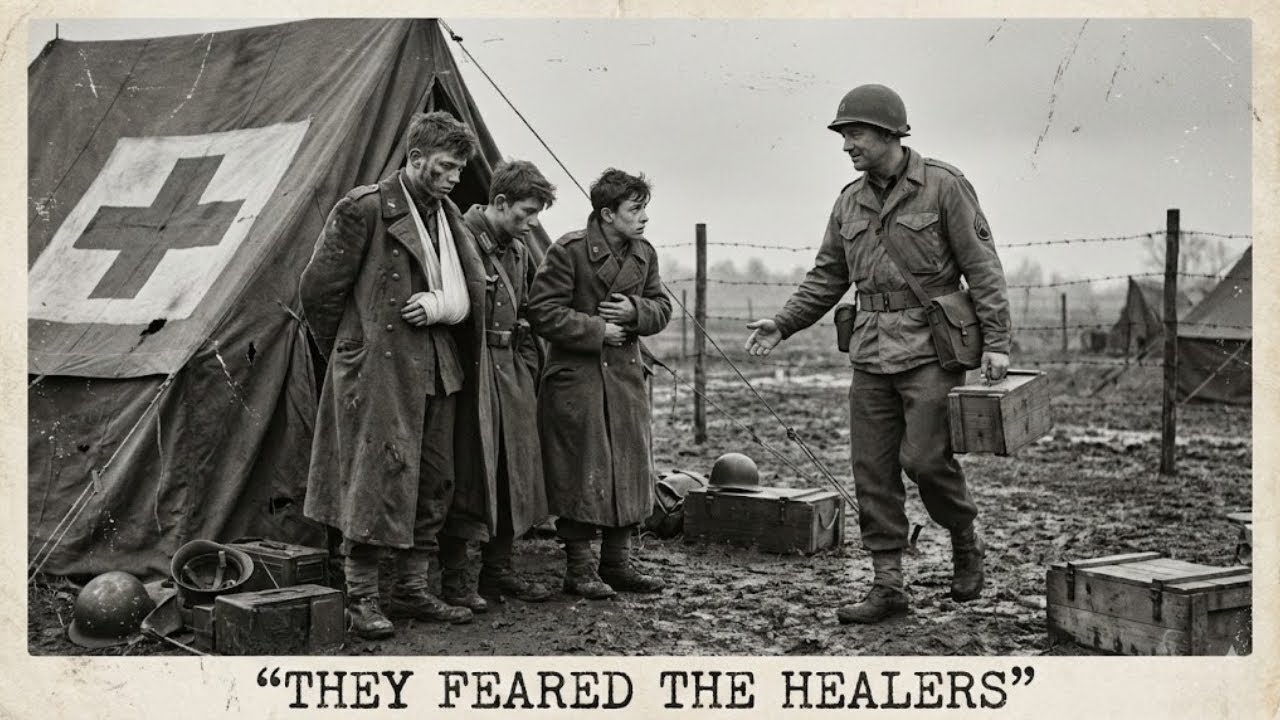

German Child Soldiers Hid Their Injuries — Fearing American Doctors Would “Finish Them Off”

June 14th, 1944.

Camp Ellis, Illinois.

The rusted teeth of the harvesting machine bit into flesh and bone before Andreas Keller even realised what had happened.

He felt the impact first—a dull, wet shock against his shin—then the warmth spreading through the thin, sweat‑darkened cotton of his trousers. When he looked down and saw the blood, a bright, arterial red against the dust and dirt of the Illinois field, his first thought was not of pain.

It was of death.

Not from infection. From the Americans.

Sixteen years old, captured in France barely a month earlier, Andreas had been told the same story over and over since he was a boy: the weak were a burden on the state. The incurable, the crippled, the damaged—euthanasia was not cruelty, it was efficiency. Germany had done it. Why wouldn’t America?

He tore a strip from his undershirt, the fabric already stiff with three days of sweat and field work, and wrapped it around the gash. He pulled it tight, tighter still, until his vision blurred and a low hum filled his ears. Then he forced himself upright and went back to work.

In his mind, the calculation was simple. If the Americans saw how badly he was hurt, they would not waste medicine on him. They would put a bullet in his head or march him to a gas chamber.

Among the rows of corn, the other prisoners watched him limping. Not one suggested the camp doctor. They had heard the same rumours in the freight cars and the barracks, whispers recycled so many times they had hardened into fact: the Americans practised euthanasia, just like the Reich. It was what modern states did.

By the third day, the fever gave him away.

A War Fought Inside the Head

In 1944, the American heartland sat at a strange crossroads of war. Over 370,000 Axis prisoners were spread across the United States, held in more than 500 camps from Texas to Minnesota. They picked cotton, cut timber, harvested wheat. They built roads and mended fences under armed guard.

Most were German soldiers. Some were boys like Andreas, conscripted out of the Hitler Youth when the Reich began feeding children into the line.

They arrived in America thin, exhausted, many already wounded. Some expected execution. Others imagined slave labour until they dropped. Almost none expected what they found: three meals a day, bunks in heated barracks, pay in camp scrip, chaplains and mail calls and soccer matches organized on dusty parade grounds.

On paper, Camp Ellis was typical. Built in 1942 on the flat prairie near Ipava, Illinois, it housed American troops, engineers, and by mid‑1944, nearly 4,000 German POWs. The Geneva Conventions were followed with bureaucratic thoroughness. The guards were a mix of older reservists and young men with medical deferments.

By any objective measure, it was not a brutal place.

And yet Andreas and his comrades were terrified.

Propaganda does not stop at borders. It travels inside people.

Andreas had grown up on a farm outside Leipzig. His father was killed on the Eastern Front in 1942. His mother, overwhelmed and alone, sent him into the Hitler Youth because that was what one did. By late 1943, the youth camps were no longer just for marching and songs; they had become pipelines into Wehrmacht units.

He received two weeks of training, fired a rifle three times, learned how to hold a Panzerfaust he would never use. In the confusion of France, his unit collapsed under American pressure. On the second day, surrounded and out of ammunition, he surrendered with his hands up and his eyes on the ground.

The GI who took his weapon gave him a cigarette and a canteen of water.

It was the first crack in the wall.

But cracks are not collapse. In the camp, older men who had fought in Poland and Russia spoke in low voices about what they had seen before the war: the T4 programme, the “mercy killing” of disabled Germans in hospitals; the way efficiency and ideology wrapped around each other until death became a budget line. If Germany eliminated its own weak, why would an enemy nation waste penicillin on captured boys?

The rumours bred in that soil.

So when the harvester blade opened Andreas’s leg, he did the most rational thing he could imagine. He hid it.

The Moment of Contact

The infection announced itself with a red line crawling up from the wound, then a heat that pulsed beneath the skin. The flesh around the cut swelled and turned waxy. Yellow fluid seeped through the filthy cloth.

He tightened the bandage again. He stole aspirin from another prisoner’s Red Cross parcel. He drank water until his belly hurt.

By the evening of June 17th, he could no longer stand without clinging to the bunk. His vision doubled. His hands shook uncontrollably.

This time, the choice was taken from him. The men in his barracks called the guard.

The guard was a corporal from Ohio named Eddie Harmon. He had never seen the front. Flat feet and bad eyesight had put him in khaki without ever giving him a rifle. But he knew what a raging infection looked like.

He took one look at Andreas and swore. Then he yelled for the medics.

That was when Andreas started screaming.

Not from pain—from terror. He fought the hands that lifted him onto the stretcher. He begged, in broken English and frantic German, for them not to kill him. The other prisoners watched in silence as the stretcher passed, some turning away, certain they were witnessing his last moments.

The infirmary at Camp Ellis was bright and smelled of disinfectant and soap. Andreas had never seen anything like it. The nurse cut away the bandage with practiced efficiency. The leg beneath was an angry, weeping mess, the edges of the wound beginning to blacken.

The American doctor examined it, expression unreadable, then spoke to the nurse in English. Andreas didn’t understand the words, but he understood the syringe they prepared. Of course, he thought. Poison. Cheaper than a hospital bed.

He closed his eyes and waited to die.

Six hours later, he woke up.

The fever had broken. His leg was wrapped in clean white gauze. A glass bottle hung beside the bed, a clear tube running into his arm. He stared at it, confused, then at the nurse who was checking his pulse.

She smiled at him.

He asked in German why he was still alive. She didn’t understand a word, but she patted his hand and said something soft in English. Later she brought him broth and bread. He ate slowly.

Then, for the first time since his capture, he cried.

Learning a Different Logic

By 1944, American factories were producing penicillin at an industrial scale—hundreds of billions of units a month. It poured into field hospitals from Normandy to New Guinea, turning once‑fatal infections into recoverable wounds.

It poured into POW wards as well. Not as charity. As policy.

The Geneva Conventions required that prisoners receive medical care equivalent to that of the captor’s own soldiers. The United States, with all its flaws and blind spots, had chosen to be bound by that law—and to take that binding seriously.

For boys raised in the intellectual climate of the Third Reich, this was almost impossible to process.

They had been taught to measure human life by utility. The weak, the disabled, the unwanted: first mocked, then marginalised, then quietly removed. Mercy was not just rare; it was suspect. To care for the “unfit” was an act against the health of the state.

To wake up alive after expecting euthanasia was not just a relief. It was a contradiction.

And contradictions demand resolution.

Andreas spent nine days in the infirmary. The infection retreated. The wound began to close. Twice, a camp officer came to ask why he had hidden the injury. Andreas answered honestly: he believed he would be killed.

The officer stared at him for a long moment, then shook his head and left without comment.

When Andreas returned to his barracks, given a tin of sulfa powder and instructions to keep the wound clean, the other prisoners crowded around. They touched the bandage, asked what had been done to him. He told them.

Some believed him. Some did not.

The wall of belief does not fall in a single blow. It erodes, grain by grain.

Boredom, Law, and the Slow Work of Mercy

Life in an American POW camp was not dramatic. There were no soaring speeches about democracy, no organized re‑education programmes in 1944. There were just routines:

Breakfast at seven.

Work details at eight.

Lunch at noon.

Roll calls, medical checks, mail distribution.

Lights out.

It was predictable. It was dull. It was safe.

In that monotony, a different lesson took root. Boys who had arrived expecting murder discovered, day after day, that nobody was coming to kill them. The guards could be brusque, even hostile, but they followed rules. Doctors treated infections. Nurses changed bandages. Chaplains—Protestant, Catholic, sometimes German‑speaking—visited the sick.

By war’s end, over 430,000 Axis prisoners had passed through American camps. Fewer than one per cent died in custody, mostly from illness and accidents. There were no mass executions, no deliberate starvation programmes.

This was not because Americans were inherently more virtuous. It was because Americans had written laws, signed treaties, and built institutions that demanded restraint—and then enforced that demand on ordinary bureaucrats and medics and guards.

The machine did not need anyone to love their enemies. It only needed them to follow the rules.

Wounded prisoners receive care.

Full stop.

A Life After Fear

Andreas Keller stayed at Camp Ellis until the spring of 1946. He worked in the kitchen, learned halting English, read American newspapers. He listened to radio broadcasts about the fall of Berlin, the liberation of the camps, the Nuremberg trials.

He watched fellow prisoners break down when the photographs from Auschwitz and Dachau circulated through the barracks. Some refused to believe. Some shouted that it was Allied fabrication. Others went quiet in a way that never really ended.

Andreas went quiet.

He realised he had believed the rumours about American euthanasia because, deep down, he knew what his own country had done. He had trusted the logic of cruelty because cruelty had been presented to him as logical.

Now he was living inside a different logic. A system that had chosen—imperfectly, inconsistently, but genuinely—to bind power with rules that protected even its enemies.

On a warm day in May 1946, he was told he would be sent home. He asked for paper. He wrote to his mother in Leipzig: I am alive. I have been treated well. I was wrong about the Americans.

He didn’t know if the letter would reach her. The postal service in occupied Germany was chaos. Four months later, it landed in her hands. She kept it until her death in 1971.

Andreas returned to a broken country, became a schoolteacher in Bavaria, raised a family. He rarely spoke about the war. When he did, he told one story: a rusted blade in an Illinois field, the fear of being killed for the sake of efficiency, the shock of waking up in a clean bed with his leg bandaged and a nurse who smiled without knowing his name.

He didn’t tell it as a story of American sainthood. He told it as a warning.

What happens when a society teaches its children that some lives are not worth the cost of care.

What happens when efficiency replaces conscience.

What happens when law serves power instead of restraining it.

He told his students that civilization is not defended by passion or purity, but by dull things—paperwork, oversight, procedures followed even when no one is watching. Rules that apply even to those we’ve been taught to hate.

In the summer of 1944, a boy hid a wound because he believed healing was a lie.

He survived long enough to learn that sometimes the only thing standing between mercy and murder is a rule that says: treat the prisoner.

And people willing to obey it.