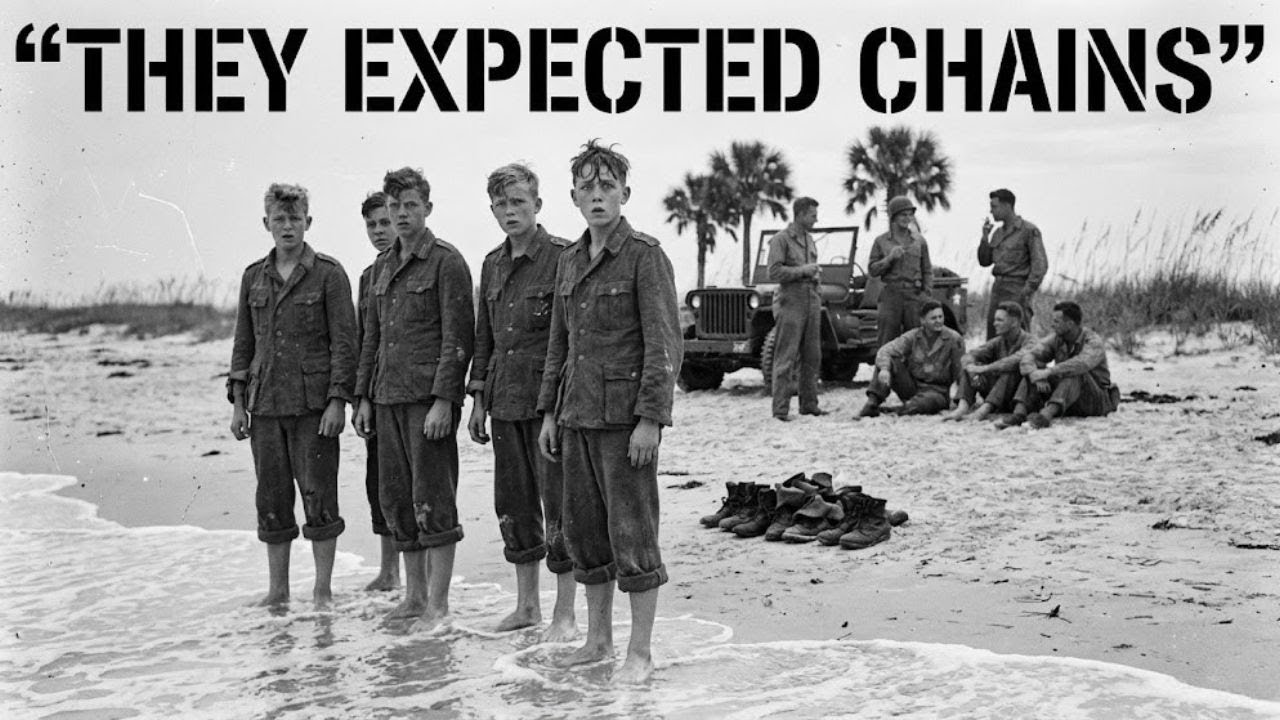

German Child Soldiers in Florida Were Taken to the Beach – Why Americans Just Let Them Swim?

The Day They Thought Florida Would Kill Them

May 17th, 1945. Camp Blanding, Florida.

The truck didn’t look like mercy.

It looked like a sentence.

Fourteen boys sat shoulder-to-shoulder in the bed, their gray wool uniforms darkening with sweat. The canvas cover trapped heat like a lid on boiling water, and the air inside smelled of damp cloth, fear, and metal. No one spoke—not because they had nothing to say, but because speech felt useless in the face of what they believed was coming.

They were sure the Americans were driving them to their execution.

They had heard stories—whispered in barracks, repeated with the certainty of scripture. Americans drowned prisoners to save bullets. Americans fed men to alligators in swamps. Florida, they said, wasn’t a holding camp. It was a death camp with better manners.

The boys had no reason to doubt it. In the final months of the Reich, they had seen what a uniform could justify. They had watched their own officers shoot deserters without trial. They had heard the word “coward” used like a verdict. They had lived long enough inside a collapsing system to understand a brutal rule: when power gets frightened, it stops pretending.

So as the truck rattled away from the compound gates, the boys counted each turn like steps toward a gallows. When the road shifted off the main route, when the tires began to crunch over something lighter than dirt, when the air grew thick with salt, their bodies tightened with the silent preparation of people trying not to beg.

Then the truck stopped.

A hand yanked the canvas flap open.

White light poured in so hard it felt like a blow. The boys squinted, blinking through glare—and saw not swamp, not barbed wire, not a firing line.

They saw the Gulf Coast.

A blue-green horizon stretched so wide it didn’t seem real, as if someone had painted a different world and accidentally rolled it out in front of them. The wind carried the smell of salt and sun. Waves folded and unfolded on sand that looked absurdly clean. The scene didn’t match the stories. It didn’t match the war. It didn’t match anything they had been trained to expect from an enemy.

For several seconds, the boys just stared, suspended between relief and suspicion.

This was not how soldiers died.

They weren’t soldiers, not really

If you looked at them through a propaganda lens, they were defenders of a nation. If you looked at them through history, they were something else entirely: the final scrape of a collapsing state, boys drafted into uniforms because there were no men left to draft.

Most were fourteen to sixteen years old, conscripted during the winter of 1944 when Germany’s military reality turned desperate enough to cannibalize childhood. Some had held rifles before they understood why. Some had been told to aim for tank treads while adults shouted orders behind them. They weren’t old enough to shave, but they were old enough—apparently—to die.

They had been fed a version of the world where kindness was a trick and mercy was weakness. They were taught that democracy was soft, that Americans were decadent, that enemy compassion was a lie designed to lure you into humiliation. And when you are young and frightened and the only adults in your world speak with certainty, certainty becomes truth.

Then they were captured—some in forests, some in ruins, some in villages that no longer felt like villages. They were processed, photographed, put on ships, and sent across the Atlantic into a land they had been taught to hate.

Camp Blanding was enormous, sprawling across pine forest and swamp. Thousands of prisoners cycled through. There were guard towers and fences and routines designed to keep order—but compared to what the boys had imagined, it felt almost unreal. They were given food. Clean water. Medical care. Not as a favor, but as procedure.

And procedure—when you’ve been raised inside fanaticism—can be more disorienting than cruelty.

Because cruelty fits the story. Procedure breaks it.

The sergeant who didn’t understand fear the way they did

The guard who climbed onto the sand that day wasn’t a monster, and he wasn’t a saint. He was simply a man who had been to war and come back with a strange conclusion: suffering didn’t need help.

His name, in the story the boys remembered, was Bill Travers—thirty-two, from the Florida Panhandle, reassigned stateside after earlier service. He looked at the fourteen boys in wool uniforms and saw what their own officers hadn’t: not enemy zealots, but exhausted teenagers who had been used up by a state that was already dead.

He gestured at the water and spoke in broken German.

“Hot day,” he said.

Then, with a simple movement of his hand, he gave them an order that didn’t belong in any of their mental categories:

“Go cool off.”

The boys didn’t move.

They glanced at each other, searching faces for instructions. One—fifteen, named Klaus in one later account—whispered the question that carried all their upbringing inside it:

“Is this a test?”

Travers didn’t catch every word, but he caught the meaning. He laughed—not cruelly, but with the bafflement of a man realizing how far propaganda can reach. Then he mimed swimming, exaggerated it until it was impossible to misunderstand.

“Water. Swim. Go.”

Still, they hesitated. In their world, hesitation had been punishable. Obedience had been survival. But the order in front of them wasn’t “dig,” “march,” or “fire.”

It was… enjoy yourself.

And enjoyment, for them, had started to feel like treason against reality.

The first laugh in a year

Finally, one boy stepped forward. Taller than the rest, all elbows and angles, the kind of adolescent body still trying to decide what shape it wanted to be. He unlaced his boots, peeled off his wool jacket, and stripped down to his underwear with a stiff, careful motion, like he expected someone to shout “Stop.”

No one did.

He walked toward the surf. At first slowly, then faster, as the water swallowed his ankles, his shins, his knees. He paused at waist depth as if waiting for a gunshot that never came.

Then he dove.

When he surfaced, he was laughing.

Not a polite laugh. Not an ironic laugh. A sudden, startled laugh—like someone had cracked open a sealed room inside him and air rushed in.

The others followed.

Within minutes all fourteen boys were in the water—splashing, shouting, half-swimming, half-clinging to one another in the shallows. Some couldn’t swim at all and grabbed at friends, panicked until they realized panic wasn’t required. Others dunked their heads under and came up gasping, grinning like the act of breathing had just been reinvented.

Travers sat in the sand, lit a cigarette, and watched.

He didn’t raise his rifle. He didn’t bark commands. He didn’t count them like inventory.

He let them be children again—if only for an hour.

Why the ocean mattered more than any lecture

If you want to understand what happened to those boys on that beach, don’t make it abstract. Don’t turn it into a moral lesson too quickly. Keep it physical, because that’s how it landed.

The water was warm. The sand was soft. The sky was too wide to belong to a nation at war.

In Germany, a coast meant bunkers, mines, and machine-gun nests—a shoreline designed as a wound that never stopped bleeding. Here, the beach was where families relaxed, where children built sandcastles, where the world pretended—almost offensively—that peace was normal.

For boys raised under a regime that survived by controlling reality, that normality was a weapon.

Not because it humiliated them.

Because it contradicted everything.

A boy later wrote, in one preserved account, that for the first time since his father died, he didn’t think about the war. That sentence sounds small until you imagine what it costs to stop thinking about war when war has been your entire adolescence.

The beach didn’t “convert” them in a cinematic way. No one gave a speech. No one demanded they renounce anything. No one forced gratitude.

Instead, the boys experienced a shock that propaganda can’t withstand:

Decency that wasn’t transactional.

And that kind of decency doesn’t just make you grateful. It makes you suspicious—then confused—then quietly furious at the people who lied to you.

Soft power before the world called it that

It would be dishonest to pretend every American camp was gentle or every guard was kind. War creates abuse anywhere humans have power over other humans.

But broadly, compared to what these boys expected—and compared to the industrial cruelty of the Eastern Front—the American POW system could feel almost unreal: prisoners fed, allowed mail, sometimes paid small wages for work, sometimes offered classes and trades.

It wasn’t only sentiment. It was strategy.

The United States understood that Germany wouldn’t just be defeated. It would have to be rebuilt. Men who returned home with stories of humane treatment would carry something contagious: the possibility of a different political future.

But on that beach, the boys weren’t thinking about postwar Europe.

They were thinking: no one is screaming. No one is killing us. The sky is blue. The water is real. We are still alive.

When the sun lowered, Travers whistled. The boys came out shivering and smiling, drying themselves with rough towels, pulling on itchy uniforms over sunburned skin. They climbed back into the truck and looked over their shoulders as it pulled away, staring at the ocean as if trying to memorize a proof of life.

The most dangerous thing kindness can do

Back at camp, the story spread. At first others didn’t believe it; it sounded like a fantasy. Then more groups were taken—carefully, selectively, as a reward for good behavior.

Something changed in the camp’s internal chemistry.

The boys began to comply not out of fear, but out of hope.

And hope—controlled hope—is a force more stable than terror. Terror makes people desperate. Hope makes them invest.

More importantly, the beach broke something deeper than discipline. It broke certainty.

If Americans weren’t monsters, what else had been a lie?

If “enemy weakness” looked like restraint, what did that say about the “strength” they had worshiped?

If dignity could be offered to prisoners, then what had all that brutality at home been for?

Years later, one former boy—older then, safer then—put it plainly in an interview: That day was the day I stopped being a Nazi. I didn’t know it at the time.

That’s how real belief collapses. Not always with argument. Often with experience.

The letters in the attic

Sergeant Travers went home after the war and lived quietly. No medals for taking prisoners to a beach. No commendations for refusing to become cruel. His family later found a box of letters tucked away—written in broken English by former prisoners who wanted him to know what that afternoon had done to them.

One message said something that feels almost unbearable in its simplicity:

“You gave us back our childhood—if only for an afternoon.”

Travers never replied. He just kept the letters.

And maybe that says everything. He didn’t see himself as a hero. He saw himself as a man who, for one hour on a Florida shoreline, refused to add more damage to a world already full of it.

History remembers wars through battles and dates and flags.

But sometimes the most important shift happens in a moment no monument marks—when fourteen boys step out of a truck expecting death, and instead find the ocean.

And for the first time in a year, they laugh.