Japanese Women POWs Braced for Execution at Dawn — Americans Brought Them Breakfast Instead

April 12th, 1945.

Baguio, Philippines.

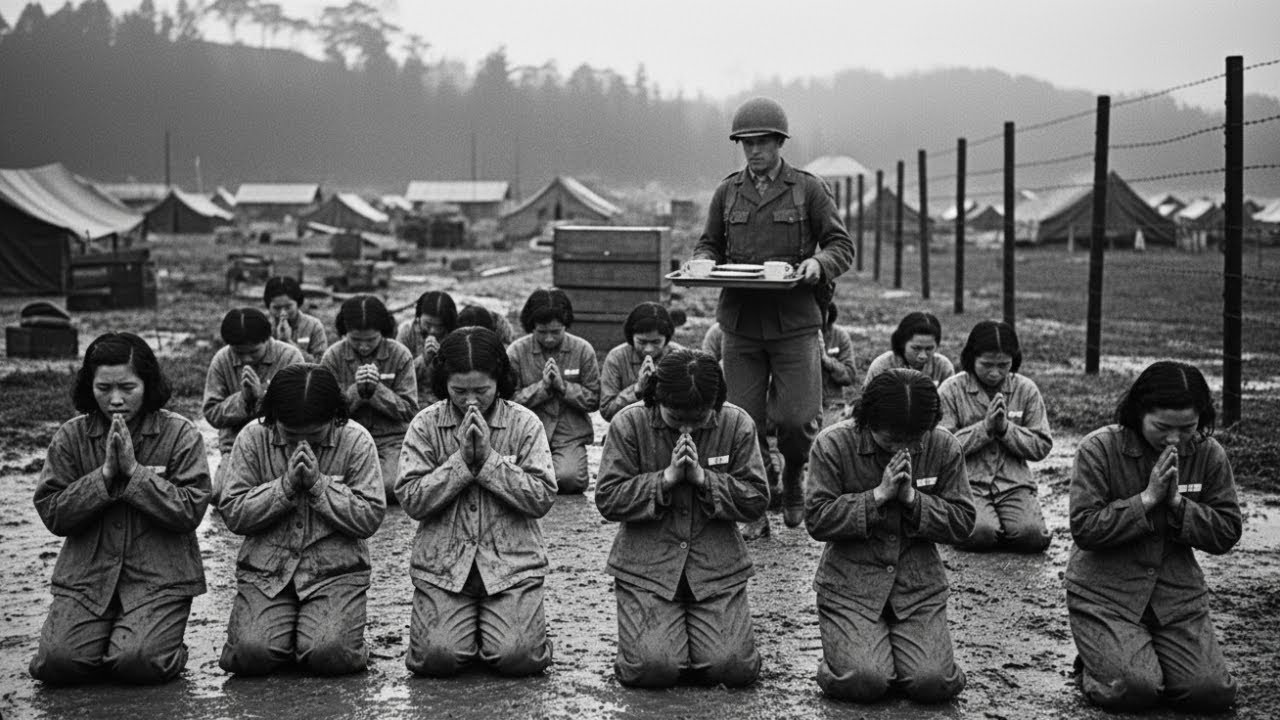

Twenty-four Japanese women knelt in the mud of a makeshift compound, hands pressed together in prayer.

They weren’t praying for rescue.

They were praying for death.

The sky above them was the color of ash—flat, bruised, exhausted. Somewhere beyond the wire, American voices carried through the morning air: short calls, clinking equipment, the casual noise of men who believed the day still held hours.

For the women in the mud, the day held only one thing.

The ending they’d been trained to expect. Swift. Brutal. Final.

And as the sound of boots approached—heavy, purposeful American boots—Lieutenant Yoshiko Nakamura closed her eyes and steadied her breathing like she’d been taught. Dignity mattered. Even now. Especially now.

She had told the others the only thing an officer could tell people who believed they were already dead:

“If the door opens, do not beg. Do not crawl. Stand.”

Her voice had been calm.

Her heart was not.

Because her mind kept playing the propaganda reels she’d been fed for years: Americans laughing as they bayoneted prisoners. Americans setting villages ablaze. Americans who took no prisoners, who gave no mercy—especially to women.

The footsteps stopped.

The compound gate swung inward.

Yoshiko braced for rifles.

For yelling.

For hands grabbing hair.

For the ritual humiliation she had been trained to fear more than bullets.

But the Americans weren’t carrying rifles.

They were carrying crates.

Food crates. Medical supplies. Blankets.

And in that moment—kneeling in Philippine mud with prayers already halfway finished—twenty-four women realized something terrifying:

If the propaganda was wrong about this…

What else had they built their lives on that wasn’t real?

If you value these untold chapters—stories about what war does to minds as much as bodies—like this and subscribe. And tell us where you’re watching from—Tokyo, Texas, or anywhere in between. Your support keeps stories like this alive.

To understand why these women were praying for death in the first place, you have to rewind six months.

In October 1944, American forces returned to the Philippines under General MacArthur. The Japanese garrison that had occupied the islands since 1942 was pushed into a desperate defensive campaign, retreat lines shifting faster than maps could be updated.

Among tens of thousands of Japanese personnel scattered across Luzon were a smaller number of women attached to the war machine—nurses, communications operators, clerks. Some had been trained in medicine and procedure. Some in code and radio discipline. All had been trained in something else, too: what capture “meant.”

Japanese doctrine wasn’t ambiguous about surrender.

Do not live to experience shame as a prisoner.

That idea wasn’t just policy. It was identity. It was drilled into bodies until it became reflex. Officers carried poison. Soldiers were taught to use grenades on themselves rather than be taken. Surrender wasn’t framed as a tactical outcome. It was framed as spiritual contamination.

And for women in uniform, the fear had a second edge. Propaganda insisted that American soldiers were barbaric—men who would violate and murder female captives, not as accidents of war, but as entertainment.

The details were rarely stated out loud.

Silence did that work.

By March 1945, as American forces pushed into the mountainous Baguio region, the Japanese perimeter began to collapse. Combat units retreated into the mountains to wage guerrilla resistance. But roughly two dozen women—nurses from a field hospital, three communications operators, administrative staff—found themselves cut off.

They hid for weeks in abandoned structures and caves, surviving on foraged roots and contaminated water. They weren’t moving like soldiers anymore.

They were moving like shadows.

One nurse—Michiko Tanaka in this dramatization—kept fragments of a diary:

“We have no food. No medicine. Fumiko is burning with fever. At night we hear American patrols passing nearby. Each night I think tomorrow they will find us. Tomorrow it ends.”

Capture came not with a firefight, but with exhaustion.

A patrol found them in the corner of a collapsed warehouse on the outskirts of Baguio—women huddled together, uniforms torn, some barefoot. When they saw the Americans, they didn’t run.

They closed their eyes.

And they prayed.

Not for mercy.

For death.

They were transported to a temporary detention compound outside the city. It wasn’t a permanent POW camp—American advances were too rapid for that. It was a guarded perimeter, a few tents, a water source, orders posted like a checklist:

Secure the prisoners.

Prevent escape.

Maintain basic humanitarian standards.

But orders did not explain what to do when prisoners refused food because they believed the food was poison.

For the first week, the women barely touched their rations—thin rice porridge twice daily, sometimes dried fish.

They were convinced the Americans were doing what cats do with mice: feeding them just enough to keep them alive until the “game” began.

Malnutrition spread. Dysentery moved through bodies already weakened by hiding. One woman’s fever—Fumiko, the sickest—deepened into pneumonia.

Lieutenant Yoshiko tried to hold discipline, but discipline felt absurd in a place where no one believed they had a future. They weren’t soldiers anymore.

They were ghosts waiting to fade.

Outside the wire, American supply trucks rumbled past, carrying ammunition and food northward. Inside the wire, twenty-four women lived in a suspended state between life and death, clinging to the only certainty they’d been allowed to keep:

Americans show no mercy.

Then came April 12th.

Captain William Morrison—thirty-four, former high school history teacher in this dramatization—arrived for a routine inspection.

He had fought through the Pacific long enough to learn how to compartmentalize. Enemy as enemy. Do what’s necessary. Don’t let your mind humanize what your hands may have to destroy.

But when he looked at the women in the compound, something broke through the compartment.

They weren’t charging. They weren’t plotting. They weren’t even speaking.

They were starving, terrified, and kneeling in mud like people rehearsing a funeral.

His interpreter—a Nisei soldier in this dramatization—explained quietly:

“They believe they’re being held for execution.”

Morrison stood in the sun, staring at people who had been so thoroughly captured by their own propaganda that they couldn’t recognize mercy even when it was offered.

And he made a decision that wasn’t in any manual.

“Get me breakfast,” he told his supply sergeant. “Real breakfast. Everything we can spare.”

An hour later, the compound smelled like a different planet.

Fresh bread. Canned meat. Fruit. Coffee. Chocolate bars.

The smell hit before the sight—warm yeast sliding under the air like a memory of kitchens, of mornings that assumed afternoon would follow. The women lifted their heads as if the scent itself had grabbed them by the spine.

Soldiers carried crates into the center of the compound and opened them.

For a long moment, nobody moved.

Not because they didn’t want food.

Because wanting food felt like stepping into a trap.

Then Sergeant Michiko—older, a nurse, the kind of woman who had learned to measure risk through practice—stood and walked forward.

She picked up a can of corned beef, turned it in her hands, then looked directly at Captain Morrison and said something in Japanese.

The interpreter hesitated before translating:

“She’s asking if it’s poisoned.”

Morrison didn’t answer with words.

He took the can, opened it with his knife, and ate a forkful himself.

Slowly.

Deliberately.

Then he handed it back.

“Tell her it’s real,” he said. “Tell her they’re not going to die today.”

That was the moment the war inside their heads began to lose.

Not because they suddenly trusted Americans.

But because reality had done what propaganda couldn’t survive:

It contradicted the script in front of witnesses.

The dam broke.

Not in a frantic rush—no stampede, no desperation.

In careful, almost ceremonial movements, the women stepped forward. They took food as if it might disappear if held too firmly. Some sat in the mud and ate immediately, heads bowed over bread like prayer had simply changed form.

Others carried food back to the sick who couldn’t stand.

The youngest—Yuki, nineteen in this dramatization—picked up a chocolate bar and held it like an artifact.

“I thought I was dreaming,” she would later say. “I thought I had died and this was the afterlife. I couldn’t understand why our enemies were feeding us.”

Food was only the beginning.

Over the next days, Morrison requisitioned medical supplies. A medic examined the sickest women and began treatment. Canvas cots replaced mud. A water purification unit provided clean drinking water.

The compound transformed from a holding pen into something closer to a facility.

And as bodies stabilized, something more complicated surfaced.

Because physical recovery is straightforward.

Psychological recovery isn’t.

Lieutenant Yoshiko struggled most. She’d been trained to lead, to uphold honor, to keep the emperor’s image intact inside her mind.

But what is “honor” when your enemy feeds you?

What is “discipline” when your own military abandoned you?

The Americans struggled too. These were Japanese personnel—the same war that had killed their friends, the same enemy that had done brutal things across the Pacific.

Yet here they were, sharing cigarettes, teaching simple English words, passing a deck of cards like boredom was allowed to exist again.

One soldier argued with another in low voices:

“We’re supposed to kill them out there,” he said, jerking his chin toward the mountains. “But here we’re supposed to be nice. Where’s the line?”

The other soldier looked across the compound at the women eating bread.

“Maybe there isn’t a line,” he said. “Maybe that’s the point.”

By the end of April, something extraordinary developed in the compound—not friendship. The gulf was too wide, too recent, too soaked in blood for that.

Something more durable:

Recognition.

Recognition that the enemy was human.

Recognition that humanity can persist even when ideology fails.

Japanese phrases were traded for English ones. A nurse consulted with an American medic. Yoshiko discussed practical logistics with Morrison—where to dig latrines, how to organize sleeping areas—matters requiring no nationalism, only common sense.

Then one afternoon, a tropical downpour sent everyone scrambling for shelter. Under a tarp, Yuki ended up beside three American soldiers. For twenty minutes they watched rain pound the dirt like it belonged to no flag.

When it slowed, Yuki looked up and said in halting English:

“Same rain. Same sky.”

A soldier nodded.

“Yeah,” he said. “Same rain.”

Small moment.

Monumental crack.

Weeks later, orders came: transfer the women to a larger facility in Manila. The small compound would be dismantled. Units would move north.

The night before departure, the women bowed—formally, deeply—not as submission, but as recognition. Morrison returned it awkwardly.

“You deserve to be treated like human beings,” he said. “I’m glad we could do that much.”

As trucks arrived, Yoshiko shook his hand.

“You showed us,” she said carefully in English, “that everything we were told was wrong.”

Morrison nodded once.

“Maybe that’s the real victory,” he said. “Learning the enemy is just people.”

And for the women who had prayed for death in the mud, the most shocking part of survival wasn’t the food.

It was what the food proved:

That the worst lies in war aren’t only about winning battles.

They’re the lies that train you to stop recognizing humanity—first in the enemy, and eventually in yourself.