Painful torture & execution of Gay Nazi SA leader & prostitute – Karl Ernst

Karl Ernst, the SA, and the Night of the Long Knives: The Rise and Fall of Nazi Power

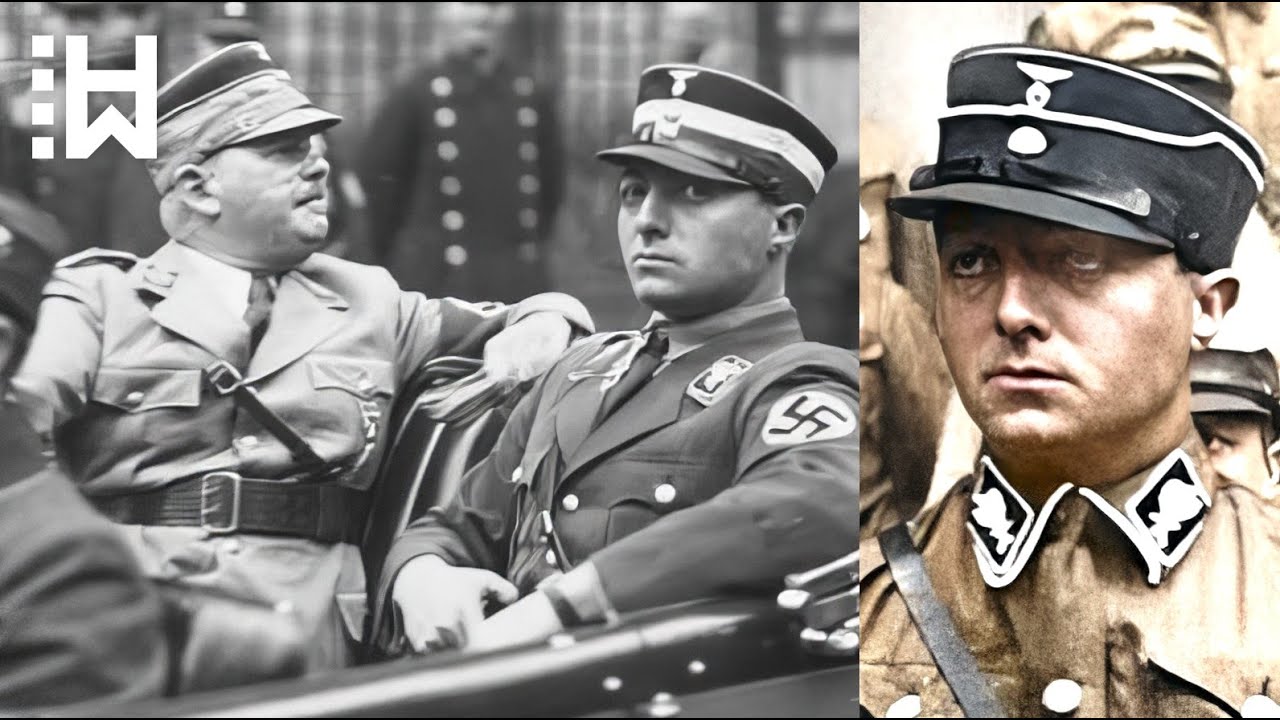

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany, bringing an abrupt end to German democracy and ushering in the era of Nazi rule. A critical component of Hitler’s rise was the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing, which grew to more than 3 million members at its peak. Led by Ernst Röhm, the SA played a pivotal role in enforcing Nazi policies and intimidating opponents. Among its leading figures was Karl Ernst, whose life and death encapsulate the violence, intrigue, and ruthlessness of the Nazi regime.

The Rise of the SA and Karl Ernst

Karl Ernst was born on September 1, 1904, in Berlin, then part of the German Empire. His father, a cavalryman, later worked as a bodyguard for Friedrich Flick, an industrialist instrumental in Germany’s rearmament. After elementary school, Ernst apprenticed as an export merchant and later worked as a hotel bellboy, bouncer at a gay nightclub, and commercial clerk in Berlin and Mainz.

In 1923, Ernst joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), also known as the Storm Troopers or “Brownshirts” due to their uniforms. The aftermath of World War I saw the proliferation of Freikorps—paramilitary groups composed mainly of veterans, who fought against communists and other perceived enemies of Germany. By 1921, about 400,000 men were involved in such groups, one of which evolved into the SA.

The SA was closely tied to the German Workers’ Party, which became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—the Nazis. The SA’s main responsibilities were to serve as Hitler’s security detail, enforce his orders, and disrupt the operations of opposing parties, often violently. Their first major action was the failed Beer Hall Putsch of November 1923, where Hitler and his followers attempted to overthrow the government. The coup failed, resulting in deaths on both sides and Hitler’s brief imprisonment.

After Hitler’s release, the SA was formally reestablished in 1925 and grew rapidly during the economic turmoil of the Great Depression. By April 1934, the SA numbered 3 million members, far outnumbering the German army.

Ernst quickly rose through the ranks, belonging to the supreme SA leadership in Munich from 1927 to 1931. He was known for his involvement in violent street battles, disrupting political meetings, and intimidating Jews, Roma, Communists, and Social Democrats—groups the Nazis labeled “enemies of Germany.”

Internal Strife and Homosexuality in the SA

Under Ernst Röhm, the SA became more organized but also more controversial. Röhm’s homosexuality was widely known, and his appointment was opposed by many within the SA who saw it as subordinating the SA to the Nazi Party’s political wing. Hitler himself claimed that a Nazi’s personal life mattered only if it contradicted the party’s principles.

In 1931, Berlin SA leader Walther Stennes rebelled against Röhm, declaring he would “never serve under a notorious homosexual like Röhm and his Pupenjungen”—a derogatory term for Röhm’s alleged male lovers, among whom Karl Ernst was included. Rumors circulated about Ernst’s relationship with Paul Röhrbein, a friend of Röhm, and he was mockingly called “Frau von Röhrbein” for this association.

Despite the controversy, Ernst continued to rise within the SA, participating in violent riots and attacks on Jews, such as the infamous Kurfürstendamm riot in 1931, where SA men assaulted Jews leaving the synagogue.

The Reichstag Fire and Nazi Consolidation of Power

After the Nazis came to power in January 1933, the Reichstag fire on February 27 was exploited by Nazi leaders to claim that Communists were planning an uprising. The resulting Reichstag Fire Decree suspended constitutional protections and paved the way for dictatorship. Some suggested that Karl Ernst and stormtroopers set the fire, but historians generally agree that Marinus van der Lubbe was responsible.

With power consolidated, the SA continued to support the regime, but Röhm’s vision of absorbing and replacing the German military became a source of embarrassment for Hitler in his dealings with traditional elites. The SA leadership’s radical demands threatened the delicate balance Hitler needed to maintain with the military and conservative politicians.

The Night of the Long Knives

By 1934, the SA’s power and Röhm’s ambitions had become intolerable. Himmler, Heydrich, and Göring conspired to eliminate Röhm, assembling a dossier of fabricated evidence accusing him of plotting against Hitler. Hitler, pressured by military leaders and conservative allies, authorized a purge.

On June 28, 1934, Hitler ordered Röhm to gather SA leaders at Bad Wiessee. On June 30, SS units, led by Dachau commandant Theodor Eicke, arrested and executed most SA leaders. Röhm himself was shot on July 1, after Hitler’s final order.

The purge extended beyond the SA, targeting right-wing nationalists and former Nazi supporters suspected of betrayal. Karl Ernst, who had planned to travel to Madeira for his honeymoon, was arrested, brutally beaten, and handed over to an SS commando led by Kurt Gildisch. After torture and interrogation, Ernst was flown to Berlin and executed by a firing squad from Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, on June 30, 1934. His death certificate recorded the time of death as 9:37 am.

Ernst died believing himself a victim of an unfortunate mistake, saluting the Nazi regime to the end. His wife, contrary to rumors, survived and died in Berlin in 1982.

Aftermath and Legacy

The German parliament retroactively legalized the killings, based on false accusations that Röhm and his commanders planned to overthrow the government. Hitler justified the purge in a Reichstag speech, alleging treason and foreign conspiracy.

The Night of the Long Knives demonstrated the Nazi regime’s willingness to bypass law to commit murder for the perceived survival of the nation. On August 1, 1934, Hitler’s cabinet passed a law merging the office of president with the chancellor, making Hitler the absolute ruler of Germany. On August 2, following President Hindenburg’s death, Hitler proclaimed himself Führer.

Karl Ernst’s death, like those of many SA leaders, was a footnote in the brutal consolidation of Nazi power. The purge marked the end of the SA’s influence, the rise of the SS, and the solidification of Hitler’s dictatorship.

Conclusion

Karl Ernst’s life and death are emblematic of the violence and betrayal at the heart of Nazi politics. The rise of the SA, its role in Hitler’s ascent, and its destruction during the Night of the Long Knives reveal the dangers of unchecked paramilitary power and the ruthlessness of totalitarian regimes. The story of Ernst and the SA serves as a stark reminder of how ambition, fear, and prejudice can shape history—and how those who serve violent causes may ultimately fall victim to the very systems they helped create.