The Stomach-Churning Things Nazis Did To Gay Men

The Unspeakable Fates: Gay Men in Nazi Germany and the Legacy of Persecution

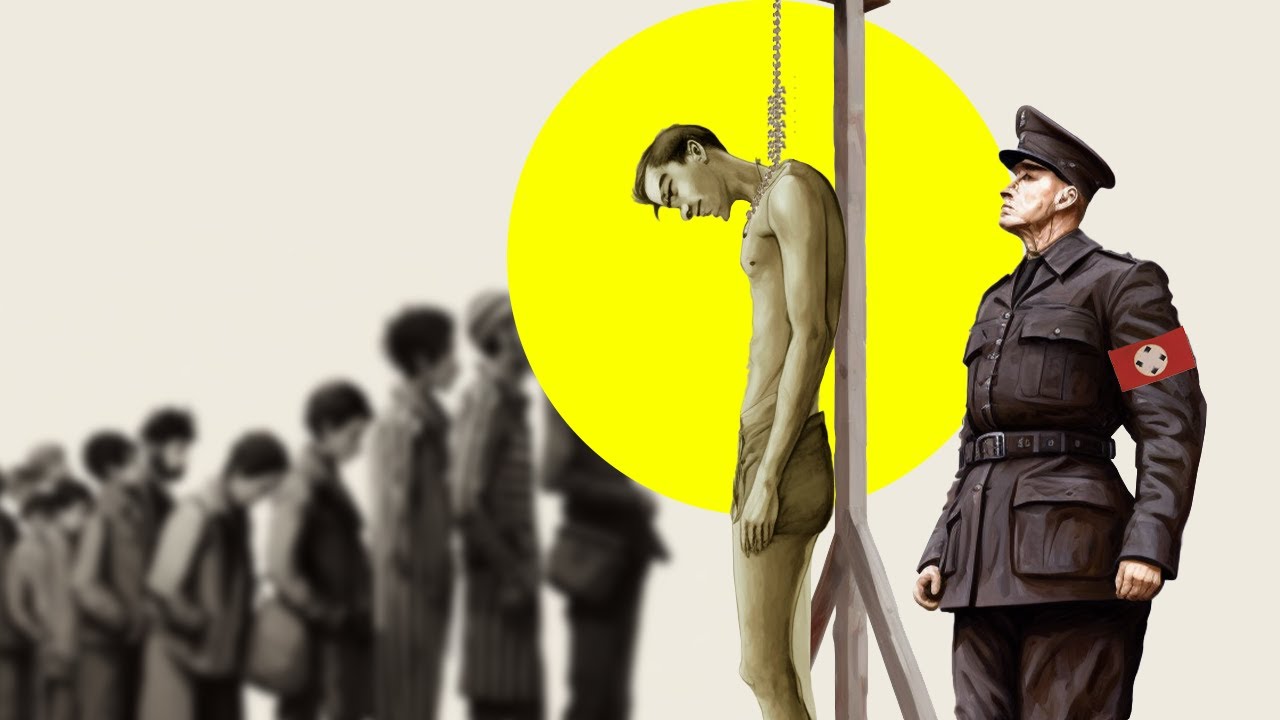

The conversation had been growing by the week. What began as murmurs of far-right thugs soon developed into a fear of a coming political party. Across bars and meeting places all over Germany, the LGBT community could sense a storm brewing. Homosexuality was illegal at the start of the 20th century, but a vibrant, thriving gay culture flourished in spite of the law. Yet, what was once angry grandstanding from a fringe party soon became national policy. In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, and a thoroughly homophobic agenda was enforced, escalating rapidly after the Night of the Long Knives. The Nazi police state made Germany’s homosexual population a primary target, unleashing persecution, arrests, physical abuse, castration, and even the horrors of concentration camps. This is the story of the unspeakable fates of gay men in Nazi Germany.

The Roots of Persecution

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they encountered a Germany with a unique history. The country was the birthplace of the first homosexual movement. In the late 19th century, Germany’s lax censorship laws and flourishing writers’ movement allowed criticism of the criminalization of homosexuality. By 1919, the first commercially sold literature for LGBTQ readers was available. However, since 1871, the German criminal code included Paragraph 175, outlawing homosexual acts between men.

The momentum of the first homosexual movement was halted by the Great Depression of 1929, and the campaign to repeal Paragraph 175 was lost. When the Nazis seized control, Paragraph 175 became a tool to realize their hateful ideology. In 1935, the Nazis revised the law, transforming it into a weapon to persecute homosexual men across Germany. What followed was the most vicious persecution of male homosexuals in history.

The Beginning of the Purge

Nazi ideology considered homosexuality deviant and a threat to their vision of society. Even those who merely thought of homosexual love were deemed enemies. Before their rise to power, Nazi politicians tied homosexuality to their long-standing antisemitism, painting it as part of a supposed Jewish conspiracy against the German people.

Starting in 1933, the Nazis cracked down on any presence of homosexuality in Germany and its occupied territories. Gay bars and clubs in Berlin, Hanover, and Cologne were forced to close, with many facing police raids. LGBTQ community members of any public visibility—from activists to sex workers—became targets. In the early 1930s, some homosexuals in smaller cities like Hamburg could still live relatively normal lives, believing the Nazi regime would end soon if they kept a low profile. Until 1935, convictions under Paragraph 175 numbered in the low hundreds, but soon after, the number of convictions skyrocketed.

.

.

.

Rohm, the Night of the Long Knives, and Aftermath

The Night of the Long Knives in June 1934 was a turning point. While its primary purpose was Hitler’s consolidation of power and the elimination of threats within the Nazi ranks, it had layered consequences for the LGBT community. Ernst Röhm, a key Nazi leader and founder of the SA, was openly homosexual. His relationship with Hitler soured, and on June 30, 1934, Röhm and other SA leaders were arrested and executed. Edmund Heines, another SA leader, was allegedly found in bed with another man when arrested.

After the purge of homosexuals within the Nazi command, the police state consolidated power under Heinrich Himmler, who headed the SS, concentration camps, and Gestapo. Himmler was, in the eyes of many historians, a rabid homophobe. From the purge of Röhm onwards, the Nazi attack on homosexuality intensified.

Persecution Peaks: 1936–1939

By 1936, Nazi ideology on homosexuality became official policy, with the German police making it a major priority. The Special Commission for Homosexuality was transformed into the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion. Urban areas became major targets for anti-homosexual policing.

In 1937, Himmler demanded police departments across Germany compile lists of homosexuals or those suspected of being homosexual. Surveillance intensified, with meeting places watched and address changes registered. Anti-homosexual measures were left to courts and police, but without additional resources, the system became clogged. Many cases were based on private conduct, virtually impossible to prove. Some police simply dragged entire classes of male youths to court and interrogated them about their sexuality.

Between 1937 and 1939, the Nazi police state arrested 95,000 men for homosexuality—an average of 600 arrests a week. Around 30,000 faced prosecution under Paragraph 175. Before the Nazis, the law allowed for prison sentences of months; now, sentences stretched to years and conviction was almost certain. The Nazi ideology of addressing “the plague” of homosexuality spilled from the lips of judges, prosecutors, and authorities. After 1937, concentration camps became the preferred method of prosecuting homosexuals.

The Pink Triangles: Camps and Cruelty

By 1935, around 80% of concentration camp prisoners held in protective custody were homosexual. Initially, these measures were for “re-education.” From 1939, any homosexual who had served a prison sentence was sent directly to the camps. Between 5,000 and 6,000 homosexual men were made prisoners in the concentration camps.

Within the camp hierarchy, homosexuals occupied the lowest rung, sharing it with Jewish prisoners. Homosexual Jews faced the worst possible treatment. Survival depended on building a social network among prisoners or being elevated in authority, but homophobia made this nearly impossible. Along with the back-breaking labor and hideous conditions shared with other prisoners, homosexuals faced specific abuses. SS guards would often physically abuse or murder homosexual prisoners for their own amusement. Mauthausen and Flossenburg had standardized practices of working homosexual prisoners to death. At Sachsenhausen, in 1942, the entire homosexual population of the camp was executed.

During the final years of Nazi rule, human experimentation favored homosexual test subjects. Carl Vaernet, a Danish doctor, infamously experimented with testosterone implants on homosexuals in hopes of changing their orientation. Most of those experimented on died afterward. Other experiments on homosexuals and Jews included typhus treatment, phosphorous burns, and drug testing. In some cases, homosexuals were castrated; up to 800 men were subjected to this “medical” torture.

The pink triangle was the symbol the Nazis used to mark the clothing of gay prisoners—a hideous tool of othering and persecution. It has since been reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ community as a symbol of resistance and pride.

Aftermath and Recognition

After the Nazi regime, discrimination against homosexuality did not end. The Allies continued enforcing Paragraph 175 in occupied territories, meaning gay men could still face persecution and prosecution. Progress was slow; it was not until 1968 and 1969 that East and West Germany decriminalized homosexuality. Any reference to Nazi persecution of homosexuals did not arise until the 1970s, following the Stonewall riots.

From there, a fervent LGBT rights movement began. In 1985, Richard von Weizsäcker, President of West Germany, was the first to officially recognize the Nazi regime’s persecution of homosexuals. In 2002, Nazi-era judgments under Paragraph 175 were annulled, and in 2017, victims were offered compensation. Little by little, progress moved forward, bringing light to the darkest corners of history.

Conclusion: Remembering and Reclaiming

The story of gay men in Nazi Germany is one of resilience in the face of unimaginable cruelty. What began as a vibrant culture was crushed by a regime determined to erase difference. Paragraph 175 became a weapon of state terror, and the pink triangle, once a mark of shame, is now a symbol of pride and remembrance.

The legacy of persecution did not end with the fall of the Third Reich. For decades, survivors continued to suffer under discriminatory laws and social stigma. Only in recent years has their suffering been formally recognized and addressed. Today, as the wheels of progress turn, the world must remember the lessons of the past. The darkness of history can only be dispelled by bringing it into the light—one story, one act of recognition, one moment of pride at a time.