They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home’

He Was Supposed to Die in a Czech Forest—Instead He Stole a Nazi Fighter and Flew It Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr glances at one gauge and realizes his life has a deadline.

The oil pressure needle has fallen to zero.

A second later, black smoke starts pouring out of the cowling of his P‑51 Mustang. Inside the engine compartment, a shard of flak has done the one thing a fighter pilot can’t outfly: it has severed the oil line. The Rolls‑Royce Merlin engine is a masterpiece—until it’s dry. Without oil, it will seize in roughly ninety seconds. After that, the propeller becomes a 400‑pound brake. The Mustang becomes a glider. And the sky over occupied territory is not a place that forgives gliders.

Carr had been leading a strafing run against a German airfield. Thirty seconds ago he was the hunter. Now he’s a dead man flying through flak.

He doesn’t hesitate. He pops the canopy, rolls the dying aircraft inverted, and drops into the freezing air.

At 8,000 feet, his parachute blossoms. Below him is enemy territory in every direction. He lands hard—twisting his ankle on impact—and immediately understands the second deadline: German patrols will be sweeping this area soon. They always do.

He has no radio. No rifle. Only a .45 pistol with seven rounds. No food. No water. And it’s November in Central Europe—cold enough at night that “sleep” becomes a gamble.

Statistics are brutal to downed pilots. Over occupied territory, most don’t “escape.” They become prisoners, names in camp rolls, or worse—graves nobody marks.

Bruce Carr is about to become the exception to almost every statistic ever written about shot‑down airmen.

Because four days from now, he won’t just evade capture.

He’ll steal one of Germany’s best fighter aircraft from a German airfield… and fly it back to the Allies while his own side tries to shoot him down.

The Kind of Pilot Who Doesn’t Think Like the Manual

Bruce Carr didn’t come from money or military royalty. He was born in Union Springs, New York, and the only “unusual” thing about his childhood was this:

At fifteen, in 1939—the year Europe caught fire—he learned to fly.

Not in some polished cadet pipeline. A local crop duster let the kid take the controls of a biplane. Carr was hooked in one afternoon. By the time he entered Army Air Forces training, he already had serious stick time—the kind of hours that turn the cockpit from a machine into an extension of your body.

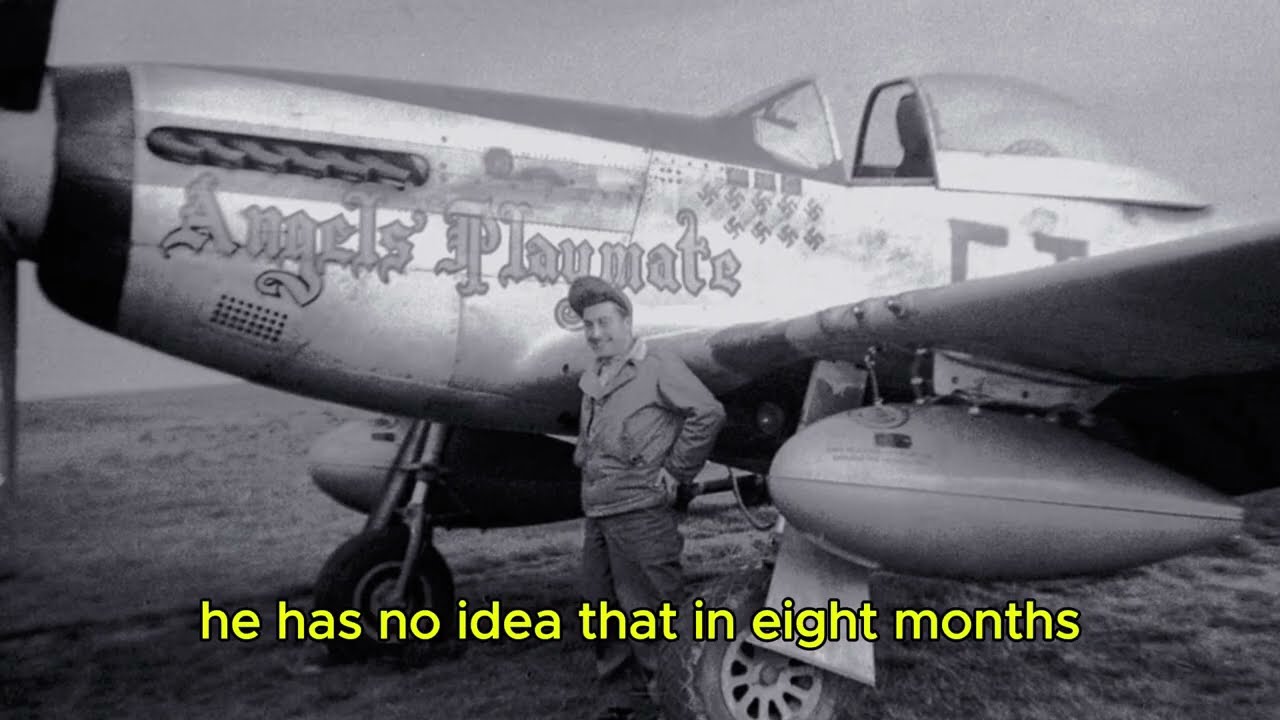

By 1944 he’s flying the P‑51 Mustang—one of the finest piston‑engine fighters of the war. Fast, long‑ranged, lethal. The kind of aircraft that finally allowed American fighters to escort bombers deep into Germany and back.

Carr loved it so much he named his plane “Angel’s Playmate.”

He also had a reputation.

In his first major chase of a German fighter, he followed the enemy down to treetop height at insane speed—an attack that made other pilots wince. He returned expecting praise. Instead, his commander chewed him out for being too aggressive. The “kill” didn’t count because the enemy pilot died trying to bail out low.

Most men learn caution from that kind of reprimand.

Carr learned something else: limits were often just habits wearing uniforms.

By autumn 1944, he was an ace. He had racked up confirmed victories and earned decorations. He had survived enough combat to know that fear is normal—but hesitation is deadly.

Then November 2 happened, and the Mustang quit being a legend and became a falling piece of metal.

The Most Counterintuitive Escape Plan: Run Toward the Enemy

After landing, Carr does something smart and cold-blooded: he hides his parachute. A visible canopy is a giant arrow that says PILOT HERE.

Then he makes a decision that sounds suicidal until you understand how searches work.

He heads north.

Toward the German airfield he had been strafing.

Because the Germans will assume a downed pilot runs away from danger—south or west, toward Allied lines. They’ll sweep outward from his landing area like ripples. They won’t expect him to crawl closer to the teeth.

But closer to the enemy also means closer to what he needs: food, water, maybe a vehicle, maybe a weapon, maybe shelter.

Maybe… an airplane.

For three days he moves through forest and cold, traveling carefully, avoiding roads, drinking from streams, hiding as patrols pass within a couple hundred yards. His ankle swells. His hunger grows into something that feels like an engine warning light inside his body.

By day three, he’s burning thousands of calories just staying warm, and he’s consumed almost nothing.

He makes the most rational decision a man in that situation can make.

Tomorrow, he tells himself, he’ll surrender.

Captured airmen—especially pilots—often ended up in Luftwaffe-run camps where survival was possible. Not pleasant. Not free. But possible.

A boring prison is better than freezing in a ditch.

Then Carr reaches the edge of the German airfield and sees something that detonates his surrender plan on the spot.

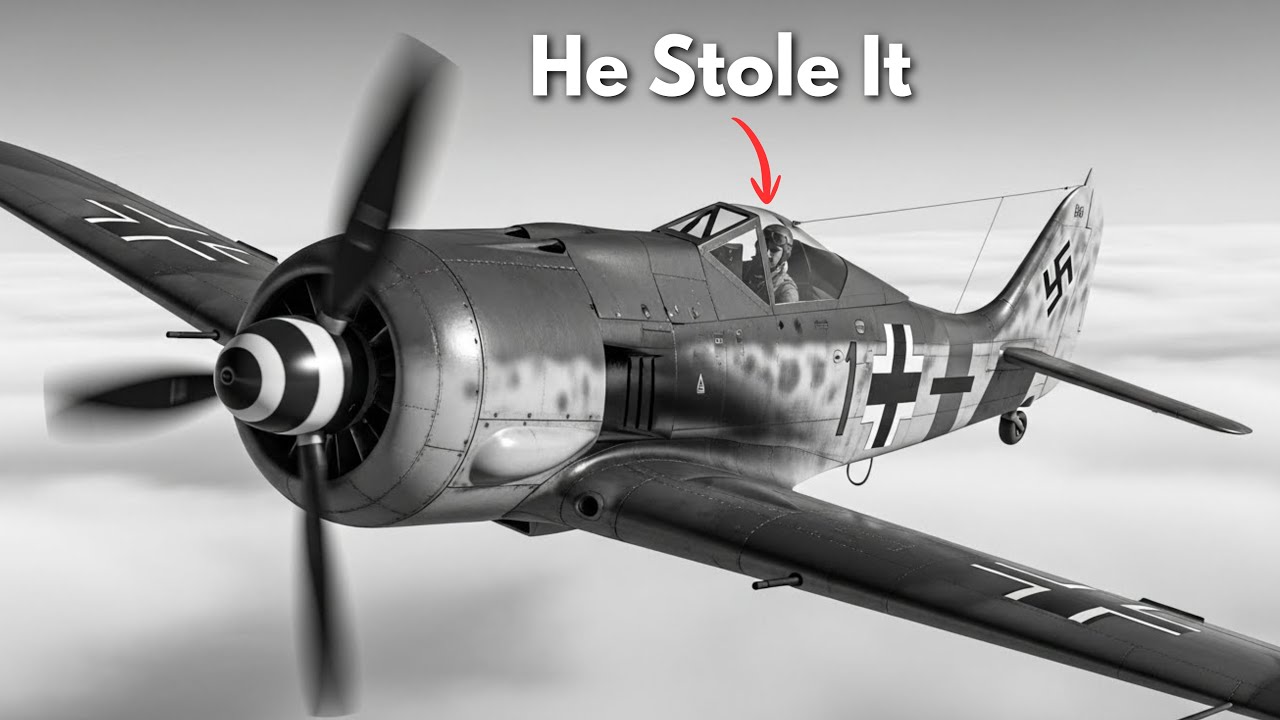

A Fully Fueled Focke‑Wulf, Left Alone Like a Loaded Gun

From a treeline overlooking the perimeter, Carr watches the airfield through branches and darkness. He can see hangars, fuel trucks, aircraft lined up like threats.

Then he notices a revetment—an earth-and-timber blast wall.

Inside it sits a Focke‑Wulf Fw 190, partially hidden under camouflage netting.

Two German mechanics are working under portable lights. Carr watches them like a starving man watching a kitchen. They check fuel. They run the engine. They cycle systems. It looks like a full preflight.

Then they shut the plane down, cover the cockpit, and walk away.

The Fw 190 is not broken.

It is ready to fly.

Carr has never flown a German aircraft. He doesn’t speak German. He has no idea where half the controls are. But he has hundreds of hours in fighters, and he knows something pilots know in their bones:

A throttle is a throttle.

A stick is a stick.

Rudder pedals are rudder pedals.

Aerodynamics do not care what language the labels are written in.

He waits until around 3:00 a.m. The airfield quiets down. Night watch thins. The world holds its breath.

Then he moves.

Eighty yards of open ground. No cover. If a sentry looks his way, he dies.

Carr crosses it low and fast, ankle screaming. He reaches the German fighter and climbs onto the wing.

The canopy is unlocked.

He slides it back and drops into the cockpit.

And immediately hits the first wall: he can’t read anything. Gauges and switches are labeled in German script. The panel is a dense forest of unfamiliar instrumentation.

He has only a few hours before dawn—before the airfield wakes up and he’s trapped inside the most obvious hiding place imaginable.

So he does what he always did: he treats the impossible like a checklist.

He identifies instruments by position and logic. Airspeed, altitude, engine cluster. Fuel selector. Magnetos. He traces lines. He touches switches carefully, like a man disarming a bomb.

Then he finds something critical: an inertia starter handle—something he recognizes not by language, but by feel.

He winds it up.

The cockpit fills with a rising mechanical whine.

He waits.

Then he engages.

The BMW radial coughs once, twice—then roars to life with a sound that can’t be mistaken for anything other than a fighter engine waking up.

Every German on the field will hear it.

Carr has just traded stealth for speed.

He shoves the throttle forward.

The Fw 190 lurches. Tail up. Nose heavy. Hungry to fly.

He doesn’t have time to find a runway. He aims between hangars in the darkness, using instinct and sheer nerve as his navigation system.

At around 90 mph, he pulls back.

The aircraft leaps off the ground and clears the hangar roofs by what feels like inches.

Bruce Carr is airborne—in a stolen German fighter—two hundred miles behind enemy lines.

The Twist: He Escapes Germany… and Enters the Most Dangerous Airspace of All

Now he has to cross into Allied territory, and you’d think that’s where things get safer.

It’s where they get worse.

Carr drops low—treetop level—because altitude makes him visible to radar and flak. At fifty feet, he becomes a fast-moving shadow.

For nearly an hour he drives the stolen fighter west, the countryside blurring beneath the wings, his brain solving one problem at a time.

Then he crosses the front.

And Allied gunners see exactly what their training tells them to see:

a German Fw 190 charging toward Allied positions.

They open fire.

Tracers reach up. Machine guns chatter. Rifles snap. Every nervous trigger finger in France wants to be the one that drops the intruder.

Carr has no radio that can make the right people understand. No friendly markings. No flare system he trusts. The plane still wears German crosses and a swastika. To the men below, he is the enemy.

So Carr does the only thing left:

He flies even lower.

At times, he’s twenty feet off the deck, “hedgehopping,” prop wash kicking up dust, civilians diving into ditches as the stolen fighter screams overhead.

He is being shot at by the people he’s trying to reach.

And the aircraft is taking hits.

But it keeps flying.

The Final Insult: The Landing Gear Won’t Come Down

He recognizes his home field. He lines up to land—fast, urgent, desperate.

Then he discovers the last problem in a chain of problems that should have killed him ten times over:

The landing gear won’t deploy.

He pulls a lever. Nothing. Pumps it. Nothing. Searches frantically for an emergency release—anything.

He doesn’t know the German hydraulic logic. He doesn’t have time to learn it.

And now the airfield’s defenses are preparing to blow him out of the sky on final approach.

Carr decides to belly-land.

He drops flaps (one control he has managed to identify correctly), cuts throttle, and brings the fighter down onto grass beside the runway.

The Fw 190 hits at speed, slides hundreds of yards, throwing a rooster tail of mud and debris, grinding metal into earth until it finally stops.

Carr is alive.

Within seconds, the plane is surrounded by military police with rifles, screaming for the “German pilot” to get out.

The canopy slides back.

And out climbs a mud-covered American in a torn flight suit.

“I’m Captain Carr of this goddamn squadron,” he snaps.

Nobody believes him. He’s been missing four days. He’s supposed to be dead or captured.

He has just returned in the wrong airplane.

Some stories are so unbelievable that even eyewitnesses reject them—until the right person arrives and stares long enough to accept reality.

The Real Bruce Carr Story Isn’t the Theft—It’s the Mindset

There are two ways to tell Bruce Carr’s life.

The first is the legend: the downed pilot who stole an enemy fighter, figured out its controls by touch, and flew it home while everyone tried to kill him.

The second is the record: an ace, decorated for valor, who later fought again and again—across multiple wars and multiple aircraft generations.

But the shocking core is simpler than either version.

In November 1944, Bruce Carr was alone, injured, freezing, and trapped behind enemy lines. The rational choice was surrender. The safe choice was giving up.

He looked at a German fighter covered in unreadable labels and saw not a locked door, but a usable exit.

He didn’t accept that his options were limited to the ones that looked reasonable.

He asked a different question—one that has saved lives in cockpits, foxholes, and disaster zones ever since:

“What else can I do?”

That question doesn’t guarantee survival.

It just creates the possibility of it.

And for four days in a Czech forest, then one violent takeoff in a stolen Focke‑Wulf, possibility was the only weapon Bruce Carr had.

It turned out to be enough.