What MacArthur Said When Montgomery Demanded Patton Be Fired After Crossing the Rhine in 36 Hours

Crossing the Rhine: Patton, Montgomery, and the Clash of Command in March 1945

March 1945. Western Germany. The war was almost over, and everyone—Allies and Germans alike—knew it. Yet, in these final weeks, some of the most consequential decisions of World War II were still to be made. On the banks of the Rhine River, under a cold gray sky, Britain’s largest military machine since D-Day stood ready for what was meant to be a historic moment: the crossing of Germany’s last great natural barrier.

Montgomery’s Masterpiece: Operation Plunder

For Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the Rhine was more than a river. It was a reckoning—a chance to redeem himself after the humiliation of Operation Market Garden, the failed airborne gamble at Arnhem six months earlier. The war had dragged through winter instead of ending by Christmas, and Montgomery, known for his meticulous planning and discipline, was determined to prove himself.

Operation Plunder was planned with obsessive attention to detail. More than 80,000 British and Canadian troops were assigned, supported by over 5,000 artillery pieces pre-registered on targets across the river. Supply depots overflowed with ammunition, fuel, and rations, calculated down to the last tin. Engineers had mapped the riverbed, prepared pontoon bridges, and rehearsed every step. Airborne divisions stood ready to drop behind enemy lines, while meteorologists analyzed wind and cloud cover. Nothing was left to chance.

Montgomery’s philosophy was clear: victory should be the product of discipline, preparation, and overwhelming force, not improvisation or reckless heroics. The timeline was set with the precision of a jeweler: at exactly 21:00 on March 23rd, the artillery would open fire; at 21:30, infantry assault boats would launch; at 22:00, engineers would begin building bridges. By dawn, British armor would be rolling across German soil, shattering the Third Reich’s last defensive line.

Montgomery’s confidence was such that he invited Prime Minister Winston Churchill to witness the crossing in person. This was to be Britain’s defining moment—a demonstration that military science, not aggression, was the true engine of victory.

Patton’s Gamble: Speed Over Ceremony

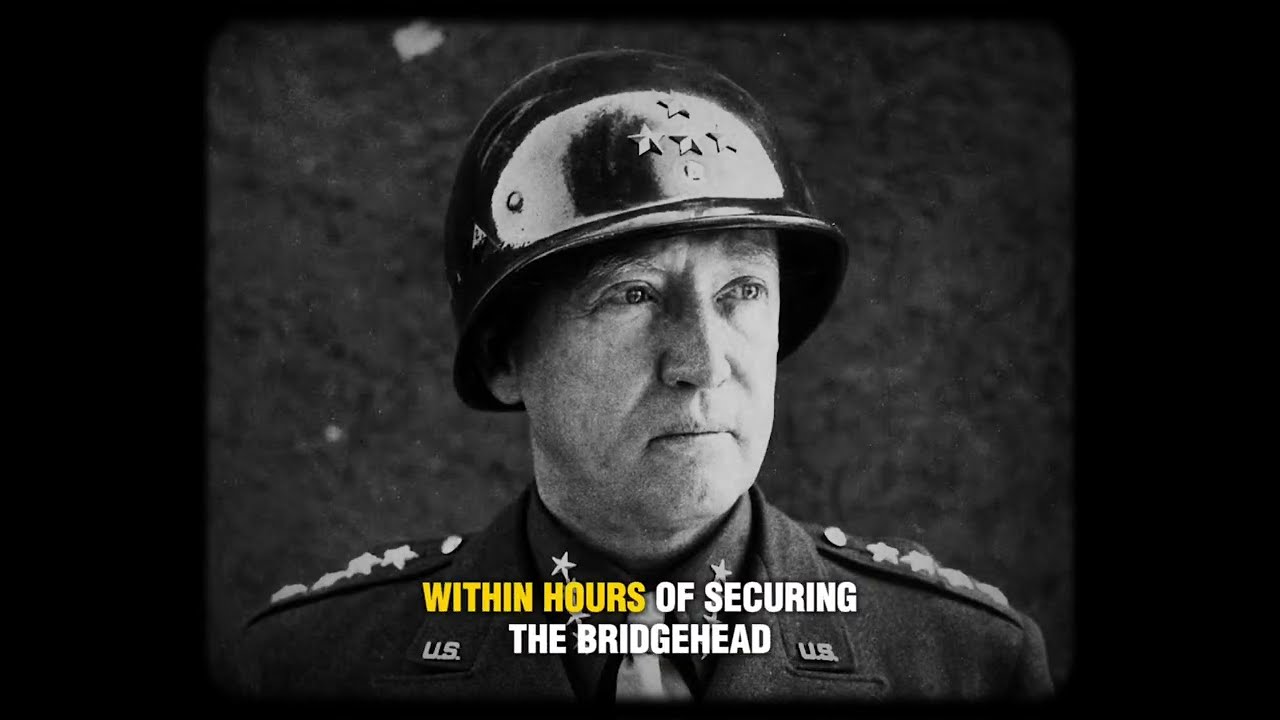

Sixty miles to the south, on the same riverbank near Oppenheim, General George S. Patton saw things differently. Patton’s Third Army had been tearing through southern Germany with relentless speed. Towns fell before defenders could organize, and German units surrendered or fled in confusion. Patton drove his men hard, stretching supply lines to the breaking point but refusing to slow down.

Patton’s rivalry with Montgomery was personal and philosophical. Where Montgomery saw war as a system of discipline and planning, Patton saw it as a contest of daring and momentum. He believed that speed itself was a form of overwhelming force, creating chaos and opportunity. To Patton, set-piece battles and rehearsed assaults gave the enemy exactly what they needed: time to adapt and reinforce.

On March 22nd, Patton’s reconnaissance patrols reported that the eastern bank of the Rhine was barely defended. German forces had been pulled north to meet Montgomery’s expected assault, leaving the southern crossings thinly held. Patton’s staff urged restraint—wait for orders, for artillery, for coordination with Montgomery. Patton listened impatiently. The Germans expected Montgomery, not him. Every day spent waiting was a day the enemy could regroup. If boldness could end the war sooner, protocol could go to hell.

Patton turned to his staff: “Get the boats ready. We cross tonight.”

The Night Crossing at Oppenheim

At 22:00, under a moonless sky, the first American assault boats slid into the water. There was no artillery barrage, no searchlights, no warning. Infantry from the Fifth Division paddled across in silence, the only sound the dip of oars and the whisper of current. They reached the eastern bank before many German sentries realized what was happening. When gunfire erupted, it was scattered and confused—old men and boys pressed into service, while veteran units rushed north.

Within an hour, a bridgehead 300 yards deep was secured. By midnight, engineers were already moving, hammering down pontoon sections and welding connection points by torchlight. At 04:00, the first pontoon bridge opened. As dawn broke on March 23rd—just as Montgomery’s artillery was scheduled to begin its bombardment sixty miles north—American Sherman tanks were rolling across the Rhine at Oppenheim.

The river that German propaganda had declared impenetrable had fallen in a single night. By sunrise, American tanks and artillery were on the eastern bank, and infantry units fanned out, securing roads and villages. Casualties were astonishingly light: fewer than 100 men killed or wounded during the initial crossing, a number far below what military textbooks predicted.

Patton arrived at the bridgehead just after dawn. He walked onto the pontoon bridge, stopped at its center, and urinated into the river—a crude but deliberate gesture, symbolic of his contempt for the barriers others saw as sacred. Patton understood the power of images and wanted the moment remembered exactly this way.

The Shockwave and the Narrative

The psychological impact of the crossing was immediate. German commanders, already stretched thin, now had to redirect reinforcements south, weakening Montgomery’s sector. The myth of the Rhine as an impenetrable shield shattered in less than 36 hours.

But the true shockwave was carried north by journalists. Patton ensured war correspondents had unprecedented access. By mid-morning, as Montgomery’s headquarters finalized preparations for Operation Plunder, newspapers across the United States were already going to print: “Patton Crosses the Rhine,” “Americans Breach Germany’s Last Defense,” “Third Army Across with Minimal Losses.” The story wrote itself—a daring nighttime assault, canvas boats, no artillery barrage, just speed and audacity.

The contrast was devastating. While Montgomery assembled 80,000 troops and 5,000 artillery pieces, Patton found a weak spot and crossed in a single night. Montgomery’s operation, still hours from launching, was suddenly no longer the centerpiece of the Rhine story.

The Fallout: Discipline vs. Initiative

At Montgomery’s headquarters, confusion and disbelief gave way to silence. There was no contradiction, no clarification—American forces were across the Rhine in strength, and bridges were operational. Operation Plunder, designed to be Britain’s crowning achievement, had been eclipsed before its first shell was fired.

For British leadership, the blow went beyond wounded pride. Britain’s military reputation was vital political capital in the postwar world. Now, at the moment meant to restore British primacy, Patton had stolen the narrative with an unauthorized gamble. How could months of planning be justified when improvisation produced faster results with fewer casualties? How could discipline be defended when insubordination appeared to deliver success?

Montgomery’s public reaction was calm and professional, insisting Patton’s action was a minor tactical maneuver. Privately, he was furious. To him, Patton’s crossing was not just unauthorized—it was an assault on the principles of coalition warfare. Wars could not be fought by lone cowboys chasing headlines. Chain of command and coordination mattered. If generals ignored strategic alignment, the system collapsed into chaos.

Montgomery drafted a formal communication to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, requesting Patton’s immediate removal from operational command. The language was precise and devastating, outlining the dangers of unilateral action and the threat to Allied unity.

Eisenhower’s Dilemma

Eisenhower received Montgomery’s message as Operation Plunder began its massive assault. Outside, Allied armies surged forward; inside, Eisenhower faced a decision that could fracture the alliance or risk undermining discipline.

Montgomery was not wrong: coalition warfare survives on trust and discipline. If one commander could ignore the plan and be rewarded, others would follow, and chaos would replace coherence. But Eisenhower also understood that wars do not wait for perfect order. Patton’s crossing had changed the tempo of the campaign, denying German commanders time to reorganize or retreat. Removing Patton would not simply punish insubordination—it would remove momentum, and in war, momentum saves lives.

Eisenhower chose to win the war first and settle arguments later. His reply to Montgomery was polite and final: Patton would remain in command. There would be no court-martial, no public reprimand, no removal. The war would move forward.

Montgomery accepted the decision, but the rupture never fully healed.

The Legacy of the Rhine Crossing

Operation Plunder succeeded brilliantly. British forces crossed the Rhine in overwhelming strength, bridges rose with mathematical precision, and casualties were light. By every professional measure, it was a model of modern warfare. Yet history remembers disruption more than precision. Patton’s crossing had already rewritten the story.

In the weeks that followed, the Third Army surged eastward with relentless force. German units collapsed, towns surrendered without resistance, and defensive lines dissolved in days. The Rhine had been Germany’s psychological anchor; once it fell, belief fell with it. By April, the war in Western Europe felt inevitable. Patton pushed until ordered to stop. Montgomery advanced methodically. Eisenhower managed egos and politics as the world watched the final act unfold.

Germany surrendered in May, but the argument did not end. Military historians still debate the Rhine crossing: was Patton’s action brilliant or dangerous? Was Montgomery right to demand discipline above all else? Did Eisenhower compromise principles for speed?

Lessons in Leadership

The truth lies uncomfortably in between. Patton proved that rigid plans can blind commanders to opportunity, and that speed and audacity can collapse an enemy faster than overwhelming force. Montgomery proved that discipline, preparation, and coordination prevent victory from turning into catastrophe. Eisenhower proved that leadership is not choosing one philosophy over another, but knowing when to tolerate contradiction.

The Rhine itself offers the final lesson. For centuries, it was treated as an unbreakable barrier—not because it could not be crossed, but because no one imagined crossing it without ceremony, permission, and overwhelming preparation. Patton did not defeat the river; he defeated the assumptions surrounding it. In doing so, he reminded the world that the most dangerous obstacles in war are not rivers, armies, or fortifications, but the rules everyone believes cannot be broken. Victory belongs to those who recognize the moment and act.