His Crew Thought He Was Out of His Mind — Until His Maneuver Stopped 14 Attackers Cold

Fourteen German fighters were closing fast—dark specks growing teeth in the winter sky. Ahead, a formation of B‑17 bombers limped home like wounded beasts, trailing smoke, leaking fuel, and shedding altitude one shudder at a time. Inside those bombers, men were already doing the math every crew learned to do in 1943: how many seconds until the next head‑on pass—and whether the next burst of cannon fire would be the one that snapped a wing or turned a cockpit into a red mist.

Then, off their nose, a single escort fighter did something that looked like madness.

The pilot didn’t peel away to chase kills. He didn’t climb high for a textbook interception. He didn’t call for help—because there was no help close enough to matter.

Instead, he moved into the bombers’ world—tight, dangerous, and violently unstable air—where a wrong inch meant collision, and a wrong silhouette meant friendly guns.

He wasn’t trying to win a dogfight.

He was trying to steal time.

Five minutes later the bombers were still flying.

And the Luftwaffe had a new kind of fear to report—one that didn’t come from superior firepower, but from a single pilot who refused to behave the way he was “supposed to.”

The Sky in 1943 Was a Factory for Death

The winter of 1943 didn’t just feel cold. It felt hostile—like the air itself had joined the enemy.

Ice formed on canopies. Breath fogged oxygen masks. Hands stiffened inside thick gloves. Below, Britain’s countryside vanished under gray fog; above, the contrails of a thousand aircraft scratched pale lines into a ceiling of war.

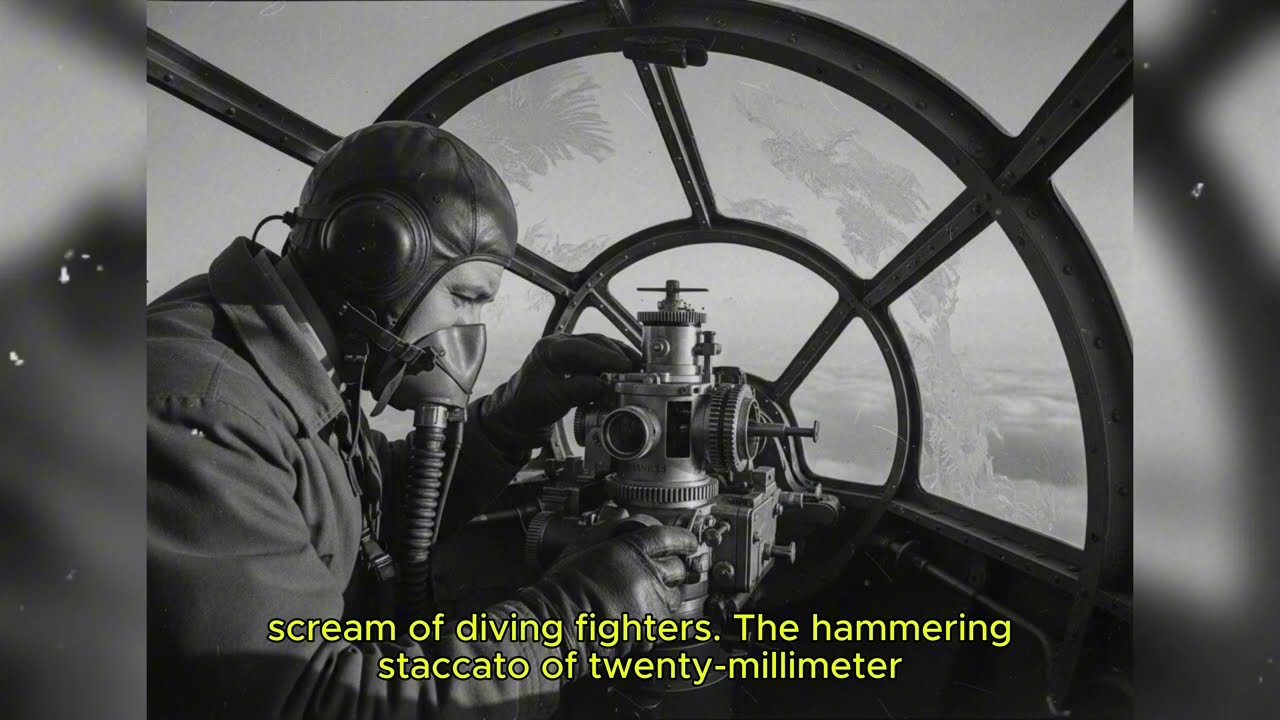

This was the height of the Combined Bomber Offensive. The U.S. Eighth Air Force committed itself to daylight “precision” bombing—an idea powered by American confidence and the promise of the Norden bombsight. In theory, waves of B‑17 Flying Fortresses would cross occupied Europe, strike Germany’s war industry, and come home sheltered by the overlapping guns of massed formations.

In practice, it was slaughter with paperwork.

German fighters learned exactly how to carve a bomber stream apart. Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke‑Wulf Fw 190s climbed above and ahead, then rolled into the signature move of late 1943: the head‑on attack.

It was brutal, efficient, and psychologically vicious.

A B‑17’s defensive guns were strong—except in the one place that mattered most during a head‑on pass: time. Nose guns had only seconds to track an approaching fighter screaming in at closing speeds that could exceed 500 miles per hour. Lead the target wrong by a hair and your tracers stitched empty sky. Lead it right and you still might not stop the pass before the German pilot fired a burst of 20mm that punched through aluminum like paper.

Bomber crews knew the truth even if briefings avoided saying it out loud:

Most Fortresses died without ever “winning” the exchange.

By December 1943, some missions were losing more than 20% of the aircraft that launched. Squadrons didn’t just take casualties. They evaporated over rail yards and industrial valleys. Crews counted missions like prison days, and every takeoff felt like placing a bet you didn’t want to make.

And the cruelest part was this: no manual taught you how to survive the head‑on pass. There was doctrine for formation discipline and oxygen management, for engine settings and emergency procedures. But not for the moment you watched a fighter come straight at your face at impossible speed and realized you had no forward-firing guns—only the hope that your gunner’s timing would be perfect.

The Man Who Didn’t Fly Like an Ace

Into that environment came First Lieutenant James H. Howard.

He wasn’t loud. He wasn’t a swaggering “ace” stereotype. He was a calm, disciplined thinker—someone who looked less like a legend and more like a man who had learned to keep his fear behind locked doors.

Howard was born in 1913 in Canton, China, to missionary parents. His childhood wasn’t built on certainty. It was built on improvisation—watching adults solve problems with limited resources and no guarantee of rescue.

He returned to the U.S., enrolled at Pomona, and studied pre‑med. But aviation pulled harder than anatomy. He joined the Navy as an aviation cadet and washed out on a minor medical issue. For most men, that would have been the end of the story.

Howard didn’t stop.

He went back to China and joined the American Volunteer Group—the Flying Tigers—months before Pearl Harbor. In the skies over Burma and southern China, he learned a kind of combat math that couldn’t be taught in calm classrooms: how to bait enemies into bad positions, how to use sun and cloud like weapons, how to survive when you’re outnumbered and isolated.

There, bravery alone wasn’t enough.

You needed ingenuity.

You needed timing.

You needed to see the fight three moves ahead.

By late 1943, Howard was in England flying P‑51 Mustangs—long-range escorts that would soon become the teeth of the bomber offensive. But in that moment the Mustang force was still developing, and the bomber stream was still being mauled.

Howard was older than most fighter pilots—thirty, a veteran in squadrons full of twenty‑two‑year‑olds. He didn’t chase thrills. He studied mission reports. He asked questions. He flew like a man solving an equation in real time.

January 11, 1944: The Moment Doctrine Failed

On January 11th, 1944, Howard launched on a deep escort mission—one of those maximum-range flights where fuel wasn’t just a number, it was a countdown clock. Fighters would have enough gas to reach the bombers, stay with them through the most dangerous minutes, and race back before their tanks ran dry.

Then weather and combat did what they always did: they broke the plan.

Cloud cover thickened. Visibility dropped. Radio chatter cracked into confusion. The bomber stream stretched out and lost cohesion—becoming exactly what German interceptors loved most: a long, disorganized target.

German fighters began appearing in disciplined flights, climbing out of haze, positioning ahead for the choreographed violence of head-on runs. Escort formations engaged. Dogfights erupted. The clean geometry dissolved into chaos.

Howard fought—fired, maneuvered, tried to stay between attackers and heavies—but then he looked up and saw it:

A detached group of B‑17s drifting away from the main stream.

No escorts in sight.

And below them, climbing in a slow spiral, a dozen or more German fighters positioning for the kill.

Howard checked his fuel. Tried the radio. Got static.

He scanned the sky for other Mustangs.

Nothing.

It wasn’t a decision taught in training. It was a blunt, brutal calculus:

Leave—and you probably make it home.

Stay—and you fight outnumbered, deep in enemy territory, with fuel already bleeding away.

Howard shoved the throttle forward and dove.

The “Insane” Move That Worked

The Germans didn’t expect a lone Mustang to challenge an entire interception. Howard exploited that fraction of surprise, firing bursts not to chase kills but to disrupt the setup—to break timing, force pilots to adjust, and turn clean, lethal geometry into messy uncertainty.

And then he did the thing that looked suicidal:

He moved in close—so close to the bombers that bomber crews would have every right to panic.

Fighter escort doctrine, as most pilots understood it, said escorts should patrol outside the formation—high cover, flanks, approach vectors—intercepting fighters before they reached the heavies. Getting too close was dangerous. Bombers flew tight wingtip-to-wingtip. Their prop wash created invisible turbulence walls. One wrong slip and you clipped a wing. Worse: bomber gunners were trained to shoot fast-moving aircraft that got too close.

But Howard understood something the doctrine writers didn’t fully respect:

The German head‑on attack depended on a clear run—straight line, high speed, unobstructed fire.

So Howard became the obstruction.

He positioned where the attackers wanted empty sky. He made them face a new choice: commit to the run and risk a collision with an armed fighter at combined closing speeds that offered almost no time to recover—or break off, reset, and try again while burning fuel and time.

They came anyway.

Head‑on passes. Slashing beams. Diving attacks from above.

Howard didn’t dogfight. He didn’t chase. He didn’t get baited away from the bombers. He kept reappearing in the attack path, forcing overshoots and aborts, turning the perfect German run into a series of imperfect, wasted attempts.

Inside the bombers, crews watched the Mustang appear again and again like a guardian that refused to leave. Over the radio, gunners began calling threats. They adjusted their fire to avoid hitting him. An unplanned partnership formed: one fighter and a cluster of bombers coordinating on instinct.

Howard fought long enough for the Germans to reconsider the cost.

He burned ammunition. He burned fuel. He took hits—rounds punching holes in his aircraft, missing critical systems by inches. His engine ran hot. His hands ached. His vision narrowed with adrenaline and oxygen debt.

But the bombers stayed together.

And slowly, the German fighters peeled away—not defeated, not routed, just recalculating as the tactical window closed and Allied cover approached.

Howard didn’t chase. He couldn’t. He was nearly dry on fuel and nearly empty on ammunition.

A lead B‑17 wagged its wings—a silent, wordless thank you.

Howard returned the gesture and turned for home.

He Landed on Fumes. The Engine Died on Cue.

Howard crossed the English coast low and landed at the first available field. The moment his Mustang rolled to a stop, the engine died—like the aircraft had been holding itself together purely out of stubbornness.

Ground crew found bullet holes in wings and fuselage. A fighter that had flown farther and stayed longer than it had any right to.

Howard climbed out unharmed, filed a brief report, and didn’t embellish.

But the bomber crews told it differently—because from inside those B‑17s, it hadn’t felt like “tactics.”

It had felt like a miracle made of metal and nerve.

Within months, Howard received the Medal of Honor for his actions on January 11th, 1944—one of the most celebrated fighter escort feats in the European air war.

And the deepest lesson wasn’t “recklessness.”

It was something rarer:

Howard didn’t save them by scoring kills.

He saved them by occupying space—by turning himself into a moving problem the enemy had to solve before they could murder the bombers.

In the end, what shocked the men who survived wasn’t just that one pilot stayed.

It was how he stayed.

Not with rage.

Not with romance.

With geometry, timing, and the refusal to accept the sky’s rules as permanent.