Yamato expected a quick kill, instead, 4 sailors did something so daring the Japanese fleet actually saluted them

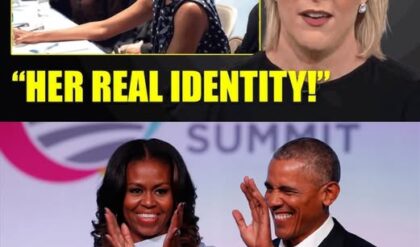

The morning of October 25, 1944, off the coast of Samar Island, was draped in a deceptive tropical haze. For the 224 sailors aboard the USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), it was just another day of screening escort carriers. They were a “tin can”—a destroyer escort built for hunting submarines, not for surface combat. Her skin was so thin it could barely stop a heavy machine gun, let alone a naval shell.

Then, at 6:58 a.m., the unthinkable happened. Emerging from the horizon were the massive pagodas of the Japanese Center Force. Leading the charge was the Yamato, the largest battleship ever constructed, a 72,000-ton behemoth whose 18.1-inch guns fired shells the size of a Volkswagen Beetle.

The Roberts weighed 1,745 tons. The Yamato outweighed her 40 to 1. Lieutenant Commander Robert Copeland picked up the intercom. His voice was steady, but his message was a death warrant: “This will be a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival cannot be expected. We will do what damage we can.”

DAVID MEETS GOLIATH

The Japanese fleet was a forest of steel: four battleships, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers. Opposing them was “Taffy 3,” a tiny American task unit of escort carriers and small tin cans. They had been left alone due to a massive intelligence failure that lured the main American battleship fleet north.

Standard Navy doctrine was clear: a destroyer escort should never engage a battleship. It was suicide. But if the Roberts didn’t act, the Japanese would massacre the slow American carriers and the thousands of troops landing at Leyte Gulf.

Bypassing the Impossible

Below decks, Chief Engineer Lloyd Trowbridge didn’t wait for orders. He knew the Roberts was rated for 24 knots. He also knew 24 knots was a death sentence. In a display of mechanical defiance, he and his crew began bypassing every safety valve and governor on the boilers.

The ship began to vibrate violently. Metal groaned. Steam pressure surged deep into the red zone. The “Sammy B” began screaming through the water at 28.5 knots—a speed her designers never dreamed possible.

THE TORPEDO RUN

Copeland ordered a charge. The Roberts had to get within 5,000 yards to fire her torpedoes. This meant sailing through five miles of plunging fire from Japanese cruisers.

Shells began to fall like rain. 8-inch rounds from the heavy cruiser Chikuma splashed so close that green dye—used by the Japanese to track their shots—drenched the Roberts’ deck. Copeland “chased the splashes,” steering the ship toward where the last shell landed, gambling that the Japanese wouldn’t hit the same spot twice.

At 7:40 a.m., the Roberts reached the “drop zone.” She launched her three Mark 15 torpedoes. Though they didn’t sink the Chikuma, the wakes forced the massive cruiser to turn away, breaking her rhythm and buying the American carriers precious minutes of life.

THE 5-INCH MARVELS

With her torpedoes gone, the Roberts had only two 5-inch guns. To the Japanese battleships, these were mere “popguns.” But Gun Captain William Burton and his crew in the forward mount didn’t care. They settle into a frantic rhythm: Load, ram, fire. Load, ram, fire.

They fired so fast—15 rounds per minute—that the paint on the barrels began to blister and peel. They targeted the superstructures of Japanese cruisers, shredded bridges, and even knocked out a turret on the heavy cruiser Tone. For a brief, insane moment, the tiny destroyer escort was holding her own against the lords of the ocean.

THE LAST SHELL OF PAUL HENRY CARR

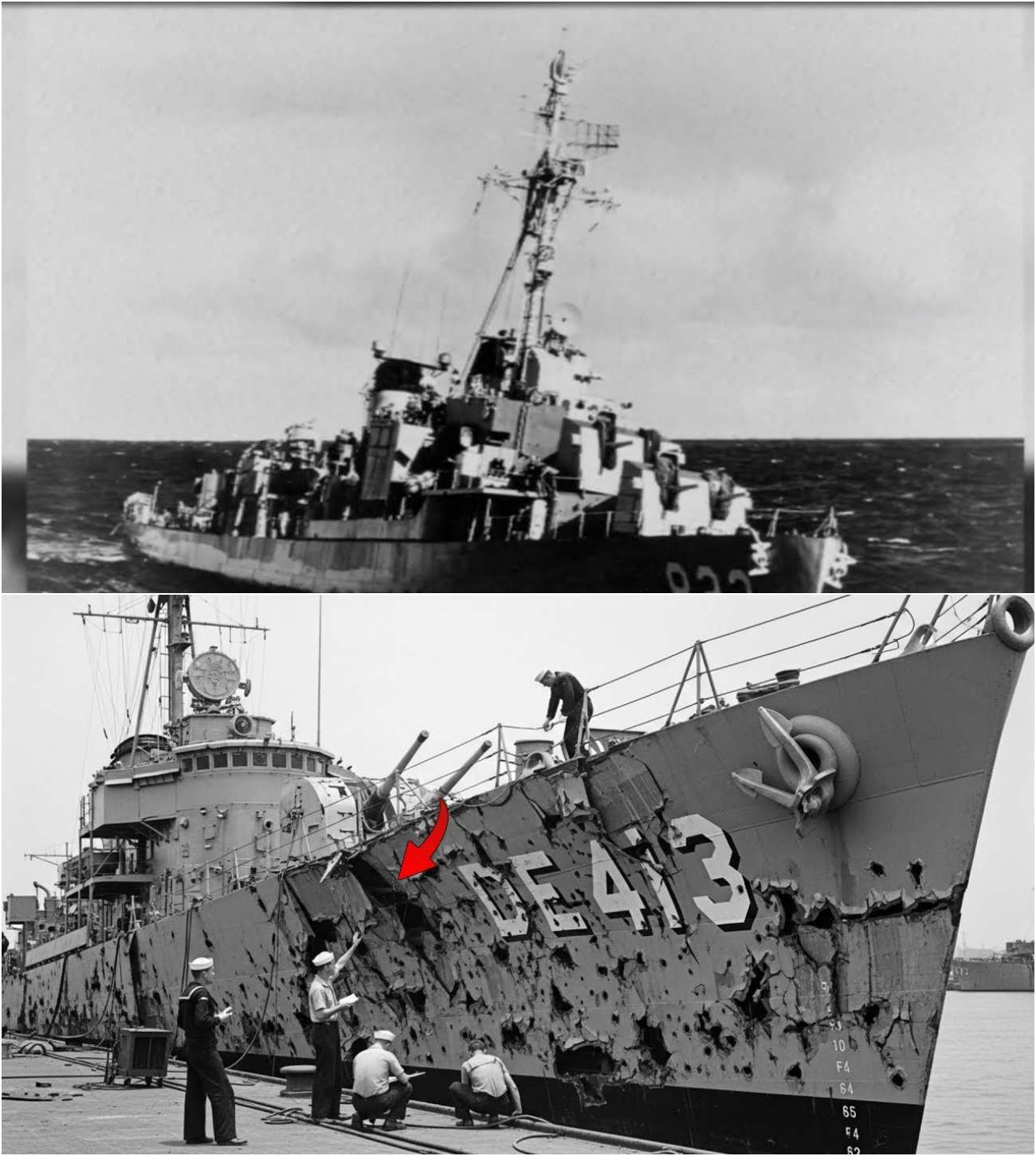

By 8:15 a.m., the Japanese had finally found the Roberts’ range. A 14-inch shell from a battleship tore through the hull, followed by 8-inch rounds that turned the ship into a charnel house.

In the aft gun mount, 20-year-old Paul Henry Carr and his crew were operating in a hellscape. Electrical power was gone. They were loading the 54-pound shells by hand in 130-degree heat. Then, a “cook-off” occurred—the overheated breech caused a powder charge to explode spontaneously.

The blast ripped the mount apart, killing almost everyone inside. When a rescue party finally reached the mount, they found a sight that left them speechless. Paul Henry Carr was on the floor, his body torn open from neck to groin. Despite his mortal injuries, he was clutching a final 5-inch shell to his chest, begging his rescuers to help him load it into the shattered gun.

He died still trying to fire one last shot for his shipmates.

ABANDON SHIP

At 9:10 a.m., dead in the water and riddled with holes, Copeland gave the order to abandon ship. The Roberts slipped beneath the waves stern-first.

The battle was won, though the Roberts was lost. The ferocity of the American “tin cans” had convinced the Japanese Admiral Kurita that he was fighting a much larger fleet. Confused and battered, the most powerful fleet in the world turned and retreated.

THE DEEPEST GRAVE

For 50 hours, 109 survivors drifted in the Philippine Sea. They battled sharks, salt sores, and the thick black oil that coated their skin. By the time they were rescued, only 95 remained.

For decades, the Samuel B. Roberts was a ghost. Then, in June 2022, explorer Victor Vescovo found her. She rests 22,621 feet down—over four miles deep. She is the deepest shipwreck ever discovered, deeper than the Titanic could even dream of reaching.

The wreck sits upright on the seafloor, her guns still pointed toward where the Japanese fleet once stood. The aft mount, where Paul Carr made his final stand, is still visible—a silent monument to the “tin can that fought like a