The “Righteous” Village: How a Protestant Town Hid 3,000 Children in Plain Sight

April 1945. In the heart of occupied France, a small Protestant village named Le Chambon-sur-Lignon stood as a beacon of hope amidst the darkness of World War II. Here, 3,000 Jewish children vanished from the face of Nazi-occupied Europe—not through deportation or concentration camps, but by simply evaporating into thin air. In this unlikely sanctuary, pastors and farmers transformed their homes, barns, and schools into underground havens for those fleeing the horrors of persecution.

The children were not hidden away in secret basements or distant forests; they walked the streets, attended classes, and played in public squares. Astonishingly, the Nazis, with their extensive surveillance machinery and terror tactics, never found them. How was it possible to conceal so many lives in plain sight? The answer lies in the unwavering resolve of the villagers of Le Chambon.

A Village with a History

The year was 1940. France had fallen to the Nazis, and the swastika now hung over Paris. The collaborationist Vichy regime turned southern France into a hunting ground for Jews. Families were torn apart, and children were separated from their parents at transit camps, where they awaited their grim fate. The terror was systematic, and the Nazi machine was efficient.

In the midst of this hell, Le Chambon, an isolated village with a population of just 5,000, became a sanctuary. Perched on the Vivarais Plateau at 3,000 feet above sea level, it was cold and poor, yet it was rich in moral courage. The inhabitants were descendants of Huguenots, French Protestants who had faced persecution for centuries. They understood the taste of oppression; their family histories were marked by midnight escapes and hideouts in caves.

When the Nazis rose to power and began their campaign against the Jews, the people of Le Chambon didn’t see strangers. They saw themselves from 300 years ago, and they made a collective decision: they wouldn’t stand by and watch. Not this time.

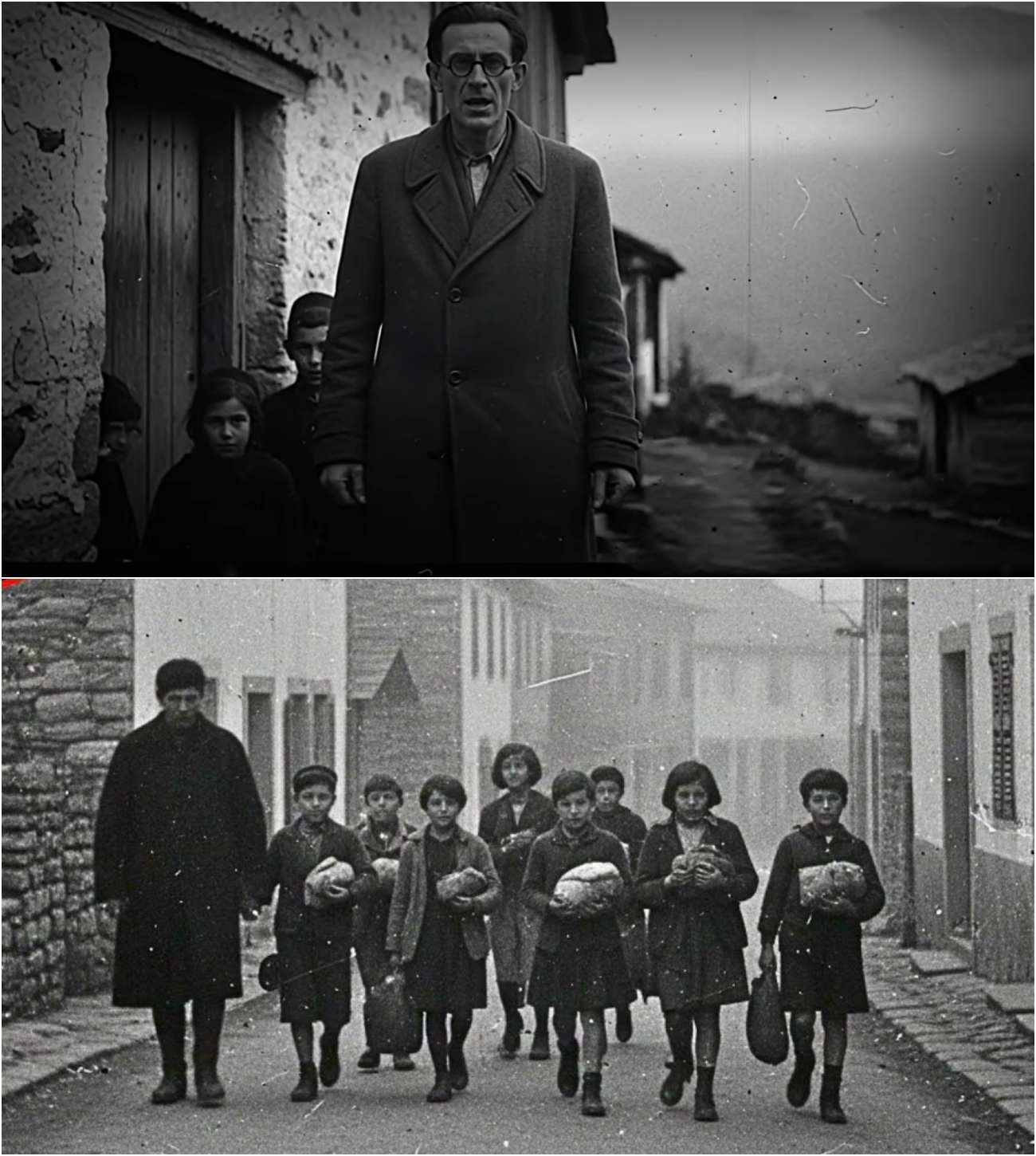

The Catalyst: André Trocmé

The movement began with one man—André Trocmé, the pastor of the local Reformed Church. Tall, with round glasses and a firm voice, Trocmé wasn’t a conventional war hero. He was a committed pacifist, influenced by Gandhi’s teachings and the theology of non-violence. In June of 1942, when the Vichy government demanded that pastors read anti-Semitic decrees from the pulpit, Trocmé took a stand. He refused.

From the pulpit of his modest stone church, he declared that his congregation had a moral duty to hide, protect, and save anyone persecuted by the regime. This wasn’t a suggestion; it was a command. Remarkably, his village obeyed.

A Mass Conspiracy

What made this story different from other tales of resistance was that it wasn’t a secret operation led by a few elite individuals. It was a mass conspiracy. Farmers, teachers, housewives, and children all participated, and everyone kept the secret. When the first Jewish child arrived in the village, knocking on a farmhouse door in the middle of the night, the farmer’s wife didn’t hesitate—she took him in.

Days later, two more children arrived, then five, then ten. Like a silent, unstoppable river, they kept coming—children whose parents had been arrested, children who had escaped from trains, children whose identities were erased and rewritten on false baptism certificates. And Le Chambon became something impossible: a sanctuary in plain sight.

The Mechanics of Survival

The villagers spread the word through underground networks. A Jewish family in Lyon, desperate and hunted, would hear a whisper from a sympathetic shopkeeper or a resistance contact: “Go to Le Chambon, ask for the pastor. They will help you.” No addresses, no guarantees—just faith in strangers.

They came on foot, by train, hidden in the backs of trucks. They arrived at night, exhausted and terrified, clutching forged papers or nothing at all. The doors of Le Chambon opened—not just one door, but dozens. The village had no central command post or sophisticated intelligence operation. What it had was something far more powerful: a shared moral certainty.

Every household became a cell in an invisible network. André Trocmé and his wife, Magda, became the quiet coordinators of this impossible operation. Their parsonage turned into a clearinghouse for human lives. Magda would answer the door at all hours, greeting exhausted refugees with a phrase that became legendary: “Naturally, come in.”

Not “maybe” or “we’ll see what we can do”—just “naturally,” as if sheltering the persecuted was the most obvious thing in the world. She would feed them, find them temporary beds, and then within hours or days, distribute them across the village and surrounding farms. Some children stayed with families, while others were placed in boarding schools run by Protestant educators, which became fortresses of false identities.

The Constant Danger

Jewish children were given new names, taught Christian prayers, and blended into classrooms alongside local kids. Teachers knew, students knew, and no one talked. But the danger was constant and suffocating. Le Chambon was under the control of the collaborationist Vichy government, which eagerly enforced Nazi racial laws. The Gestapo operated freely, and informants lurked everywhere.

The village police chief, a man named Robert Bach, could have destroyed the entire operation with a single phone call. But he didn’t. He became part of the conspiracy. When orders came down from regional authorities to round up Jews, Bach would conveniently forget to execute them. When SS officers arrived to inspect the village, he would somehow fail to find anyone suspicious. And when warnings came that raids were imminent, he would quietly pass the word to Trocmé, who would activate the alarm system the village had developed.

A coded message whispered from door to door, farm to farm. Within minutes, children would scatter into the surrounding forests, hiding in pre-arranged spots until the danger passed.

A Test of Morality

The first major test came in August of 1942. Vichy authorities, under pressure from Berlin, launched a massive roundup of foreign Jews across the unoccupied zone. Thousands were arrested, families shattered, and orders reached Le Chambon demanding that Trocmé provide a list of all Jews sheltered in the village. It was a death warrant disguised as paperwork.

Trocmé’s response was simple and devastating: “We do not know what a Jew is. We only know men.” He refused to provide any names. It was an act of open defiance that should have resulted in his immediate arrest and execution. But something unexpected happened. The authorities hesitated.

Why? Because Le Chambon wasn’t acting alone anymore. The conspiracy had grown beyond the village borders. Surrounding towns and farms across the plateau joined the network. Protestant communities in nearby towns opened their doors, and even Catholic families, inspired by the Protestants’ courage, began sheltering refugees. What started as one pastor’s moral stand had metastasized into a regional uprising of decency, and the Vichy government, terrified of igniting a broader revolt, backed down—for now.

The Nazis Close In

But the Nazis weren’t blind, and they weren’t patient. By the winter of 1942, whispers about Le Chambon had reached the highest levels of the SS command structure in France. Something was wrong in that mountain village. Too many refugees were disappearing into the plateau. Too many Jewish children were slipping through their fingers.

In February of 1943, the Gestapo made its move. A team of officers arrived unannounced, led by a captain named Julius Schmalling. They came with trucks, dogs, and a mandate: find the Jews, arrest the conspirators, and make an example of this village that dared to defy the Reich.

The entire operation should have taken hours. It took weeks and ended in failure. Schmalling understood that Le Chambon was hiding something, but he couldn’t prove it. The children he encountered on the streets all had papers. The families hosting them all had explanations: “This is my niece from Lyon. These are cousins from Marseilles.” The stories were rehearsed, simple, and impossible to disprove without extensive background checks that would take months.

And here’s where the villagers’ strategy revealed its genius. They never denied anything outright. They simply buried the truth under layers of mundane normalcy. When Gestapo officers searched homes, they found children doing homework. When they inspected schools, they found students reciting Protestant hymns. Everything looked ordinary, yet everything felt wrong.

The Standoff

But Schmalling had no evidence, and without evidence, even the Gestapo couldn’t act freely in Vichy territory without risking a diplomatic incident with the collaborationist government. The closest the Nazis came to cracking the network happened on a freezing morning in late February. Schmalling’s men raided a boarding school called Maison Desia, a three-story building perched on the edge of the village.

They burst through the doors, demanding to see identity papers for every student. The headmaster, a wiry man named Daniel Trocmé, calmly complied. He produced documents for every child. The officers examined them closely, looking for inconsistencies, forged stamps—anything that would give them grounds for arrest—and they found nothing.

But as they prepared to leave, one officer noticed something odd. A boy in the corner, no more than 12 years old, was clutching a book to his chest with white knuckles. The officer barked an order: “Show me the book.” The boy hesitated. The room went silent. Daniel Trocmé stepped forward, placing a hand on the boy’s shoulder, and explained that the child was simply protective of his prayer book, a gift from his late mother.

The officer wasn’t buying it. He ripped the book from the boy’s hands and opened it. There, tucked between the pages, was a photograph—a family photograph. The boy in the picture was standing beneath a menorah, clearly celebrating Hanukkah. The officer’s eyes lit up with triumph. He had his proof.

He grabbed the boy by the arm and began dragging him toward the door. The other children watched in frozen horror. Then Daniel Trocmé did something that should have gotten him executed on the spot. He physically blocked the doorway, telling the officer that if the boy was to be arrested, he would have to arrest Daniel as well because this child, he declared, was under his protection, and Daniel would not abandon him.

A Moment of Defiance

The standoff lasted less than a minute but felt like an eternity. The officer could have shot Daniel where he stood; he had every legal right under Nazi occupation law. But something stopped him. Maybe it was the cold certainty in Daniel’s eyes. Maybe it was the realization that executing a school headmaster in front of dozens of witnesses would turn the entire plateau into an active resistance zone.

Or maybe, just maybe, even a Gestapo officer retained a sliver of humanity that recoiled at murdering a man for protecting a child. Whatever the reason, the officer released the boy, shoved Daniel aside, and stormed out. But Daniel Trocmé’s name was added to a list, and six months later, the Gestapo would come for him.

The children, meanwhile, learned to live double lives. By day, they were Marie, Pierre, Jean—good Protestant children with baptism certificates and rehearsed family histories. By night, in whispered conversations in attics and barns, they were Rachel, David, Sarah—holding on to fragments of their true identities like precious stones.

They learned which prayers to recite in public and which ones to whisper in private. They memorized the names of fictional relatives and the details of towns they’d never visited. And they learned the most important lesson of all: silence. A single slip, a moment of confusion could unravel everything. The weight of that responsibility on children as young as five years old is almost unimaginable.

Yet they carried it because they understood, even at that age, that their survival depended on perfect performance. The village children became their co-conspirators. Protestant kids who had grown up hearing stories of their own ancestors’ persecution understood instinctively what was at stake. They covered for the Jewish children when their accents slipped, helped them memorize Christian rituals, and lied to their own relatives when necessary.

Acts of Solidarity

These weren’t acts of pity; they were acts of solidarity. The children of Le Chambon didn’t see victims; they saw friends who needed protection. And in that simple reframing, they became part of the most effective resistance cell in occupied France.

The network expanded in ways that defied logic. Farmers in the surrounding hills began forging documents in their kitchens. A local printer named Oscar Rosowski, a Jewish refugee barely 18 years old, became a master forger, producing hundreds of fake identity cards, ration books, and baptism certificates that were so convincing they fooled even Gestapo document specialists.

He worked out of a cramped attic room, using stolen official stamps and homemade inks mixed from berries and chemicals smuggled from Laon. Every document he created was a lifeline, and every day he worked, he risked a firing squad. But he kept working because in Le Chambon, everyone contributed. There were no passengers, only crew.

Food became another act of resistance. The plateau was poor, the soil rocky, and wartime rationing meant that even the locals barely had enough to eat. Yet somehow, the village fed 3,000 extra mouths. Farmers diverted portions of their harvests. Women stretched soups and stews with whatever they could scavenge. Black market networks, typically reserved for profit, were repurposed for survival.

The children, both local and refugee, were taught to forage in the forests, gathering mushrooms, berries, chestnuts—anything edible. Hunger was constant, but starvation was avoided. It was a logistical miracle performed by people who had no training in logistics, no resources, and no margin for error. They simply refused to let the children die.

The Gestapo’s Search

And through it all, the Nazis kept searching. Raids became routine. Gestapo officers would sweep through the village at random intervals, searching homes, interrogating families, trying to catch someone in a lie. But the lies held, the system held, and every time the officers left empty-handed, the conspiracy grew bolder.

By the spring of 1943, Le Chambon wasn’t just hiding refugees anymore; it was actively smuggling them out of France entirely. Guides, many of them local teenagers, began leading groups of children across the mountains into neutral Switzerland. The journeys were brutal—30 miles on foot through snow and ice, dodging border patrols, sleeping in caves. But hundreds made it, and Le Chambon became more than a sanctuary; it became a gateway to freedom.

The Swiss border crossings were nightmares disguised as hope. The journey from Le Chambon to the frontier took three days on foot through terrain that could kill you as easily as a German bullet. Guides, often barely older than the children they were leading, memorized patrol schedules, bribed border guards when possible, and relied on networks of sympathetic farmers who would hide groups in barns when patrols swept through.

The children walked in single file, forbidden to speak, their shoes wrapped in cloth to muffle footsteps. If a child stumbled or cried out, the entire group could be compromised. And the Swiss, despite their official neutrality, were not guaranteed allies. Border guards often turned refugees back, sentencing them to arrest and deportation. But the guides from Le Chambon knew which crossings were porous, which guards looked the other way, and which mountain passes were unwatched at dawn.

It was a deadly lottery. But for those who made it across, Switzerland meant survival.

A Turning Point

Back in the village, André Trocmé knew his time was running out. The Gestapo hadn’t forgotten him. His refusal to cooperate, his open defiance had made him a target. In the summer of 1943, warnings reached him through resistance channels: an arrest order had been issued. He could flee, go into hiding, continue his work from the shadows. But leaving Le Chambon would signal fear. It would embolden the authorities and tell the villagers that even their pastor, the man who had started this conspiracy, believed it was over.

So, Trocmé made a calculated gamble. He went into partial hiding, living in the village but moving between safe houses, never sleeping in the same place twice. It was a compromise between survival and symbolism. He remained visible enough to inspire, yet invisible enough to avoid capture. For months, it worked.

But in August of 1943, the Gestapo sprang a trap. Officers surrounded the parsonage at dawn, expecting to find Trocmé asleep. Instead, they found his wife, Magda, calm and unflinching, serving breakfast to a group of refugee children. The officers demanded to know where her husband was. She told them the truth: she didn’t know.

They tore the house apart, searched every room, interrogated the children. Nothing. Furious, they arrested Magda instead, dragging her to the regional Gestapo headquarters in Le Puy. It was a hostage situation. The message was clear: surrender yourself, or your wife pays the price.

And for the first time since the conspiracy began, André Trocmé faced a choice that had no good answer. Turn himself in and the network loses its leader. Stay hidden and his wife could be tortured or killed. He turned himself in. Within hours, Trocmé walked into Gestapo headquarters and surrendered.

He was immediately arrested along with his associate pastor, Édouard Trocme, and the headmaster, Roger Darcissak. The three men were thrown into a detention camp in Saint-Paul-d’Eg, a holding facility for political prisoners awaiting deportation to Germany. For the villagers of Le Chambon, it felt like the end. Their pastor, their moral compass, was gone.

The Resilience of the Village

But here’s what the Nazis didn’t understand: Le Chambon was never dependent on one man. Trocmé had lit the fire, but the village had become the fuel. The network didn’t collapse; it adapted. Magda Trocmé, released after her husband’s surrender, took over coordination. Other pastors stepped up. Farmers, teachers, and housewives who had been following orders now gave them.

The conspiracy didn’t just survive André’s arrest; it accelerated. In late August, the Gestapo came for Daniel Trocmé. They had not forgotten the schoolmaster who had blocked a doorway and refused to surrender a Jewish child. Officers raided the Maison de Rosat at dawn, dragged Daniel from his quarters, and arrested him along with 18 students—all of them Jewish, all of them betrayed by an informant whose identity remains unknown to this day.

Daniel was transported to the Compenya transit camp, then deported to the Majdanek concentration camp in occupied Poland. He never returned. On April 2, 1945, just weeks before the camp’s liberation, Daniel Trocmé died in the gas chambers. He was 31 years old. His final recorded words, according to a fellow prisoner who survived, were instructions to look after the children.

Even in Majdanek, even facing death, he was still protecting them. The news of Daniel’s arrest sent shockwaves through Le Chambon. For the first time, the village felt the full weight of Nazi revenge. Parents who had entrusted their children to the network began to panic. Some demanded their children back. Others begged for them to be moved immediately to Switzerland.

The carefully maintained calm that had held the conspiracy together for four years began to fracture. But Magda Trocmé refused to let them be shipped off to orphanages or displaced persons camps. She argued with a fierceness that shocked even the American relief workers that these children had already been uprooted too many times. They had been torn from their parents, stripped of their identities, forced to live as ghosts. They didn’t need another institution; they needed stability.

So she made an audacious proposal: let the children stay in Le Chambon. Let the families who had hidden them continue to care for them until relatives could be found or proper homes arranged. The American authorities were skeptical. How could a poor mountain village, already stretched beyond capacity, continue to feed and house hundreds of refugee children in the chaotic aftermath of war?

But Magda didn’t ask for permission. She simply continued doing what she had been doing for four years, and the village followed her lead. For months, Le Chambon became a strange liminal place—part refugee camp, part village, part orphanage. Red Cross workers arrived, documenting the children, searching for surviving relatives, trying to piece together shattered families.

Some children were reunited with parents who had miraculously survived the camps. Those moments were devastating and joyous in equal measure—skeletal mothers embracing children they hadn’t seen in three years, fathers weeping at the sight of sons and daughters they thought were dead. But for every reunion, there were ten children who waited by the parsonage door, hoping for news that never came.

Slowly, painfully, they began to understand that their parents were never coming back. The villagers who had risked everything to save these lives now had to help them grieve. Some children stayed in Le Chambon permanently. Families who had hidden them for years formally adopted them, raising them as their own. Protestant farmers became fathers to Jewish children, teaching them to tend sheep and plow fields.

Teachers who had falsified records became surrogate mothers, helping traumatized kids rebuild their identities. In one of the most remarkable acts of cultural preservation, the village made space for the children to reclaim their Jewishness. Synagogue services were held in the Protestant church. Jewish holidays were celebrated openly for the first time in five years.

A Legacy of Resistance

The villagers who had hidden these children by making them invisible now worked to make them whole again. It was a collective act of healing that lasted years and required a depth of compassion that defied measurement. And then came the question no one wanted to ask: what about justice? Who would be held accountable for the informants, the collaborators, the Vichy officials who had hunted these children?

France was tearing itself apart in postwar purges, executing collaborators, shaving the heads of women who had slept with German soldiers, settling scores with mob violence. But Le Chambon refused to participate. André Trocmé returned from his detention, horrified by the executions he saw in other regions, preaching forgiveness from his pulpit. He argued that vengeance would poison the very principles the village had fought to uphold.

Some villagers disagreed, wanting names, trials, punishment. But the majority held firm. They had resisted with nonviolence; they would rebuild with nonviolence. It was a choice that haunted some survivors for the rest of their lives. But it was also a choice that allowed Le Chambon to remain Le Chambon—a place defined not by who it destroyed, but by who it saved.

The world didn’t want to hear about Le Chambon. Not at first. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the dominant narrative was one of heroic Allied armies and defeated Nazis. There was little appetite for stories about quiet villages that had simply done the right thing. France, eager to rebuild its national pride after the humiliation of occupation, focused on glorifying the armed resistance—the Maquis fighters who had sabotaged railroads and assassinated German officers.

Pacifist pastors who hid children didn’t fit the narrative. They didn’t storm beaches or blow up bridges; they just opened doors and lied to police. And so Le Chambon was ignored. No medals, no parades, no official recognition. The villagers returned to farming and teaching and the children they had saved scattered across the world, carrying stories that no one wanted to publish.

Rediscovery and Recognition

It took nearly 40 years for the world to discover what Le Chambon had done. In 1980, an American documentary filmmaker named Pierre Sauvage traveled to the village. Sauvage himself was one of the children saved by the network, born in Le Chambon in 1944 to Jewish parents who had found refuge there. He had grown up in America, knowing only fragments of his origin story.

But as an adult, he became obsessed with a question: how had an entire village conspired to save lives when the rest of Europe looked away? His documentary, Weapons of the Spirit, finally brought Le Chambon’s story to an international audience. What Sauvage discovered shocked him. The villagers still didn’t think they had done anything special.

When he interviewed elderly farmers and teachers, they repeatedly said variations of the same thing: “We just did what anyone would do.” Except, of course, almost no one else did. The recognition, when it finally came, arrived in waves. In 1990, Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, declared the entire village of Le Chambon righteous among the nations—the only time the honor has been bestowed on an entire community rather than individuals.

Survivors who had been hidden as children began returning to the plateau, now elderly themselves, searching for the families who had saved them. Tearful reunions happened on farmhouse doorsteps. Former refugee children, now professors, doctors, and artists, embraced the now elderly farmers who had fed them scraps during the war.

The stories began to emerge in full—not sanitized, not heroic, but real stories of fear, hunger, near misses, and impossible choices. Stories of ordinary people who simply refused to accept that genocide was inevitable.

A Lasting Impact

But even with recognition came questions that still haunt historians today. How did 3,000 people keep a secret for four years? How did an entire region conspire without a single catastrophic betrayal? The answer, frustratingly, is that no one knows for certain. There’s no manual. No strategic plan was ever found. The conspiracy was oral, decentralized, and improvised.

It succeeded because it had no leader to arrest, no headquarters to raid, no written records to seize. It succeeded because every single person chose individually to participate. And that choice, repeated thousands of times by thousands of people, created something the Nazis could never infiltrate: a culture of resistance so deeply embedded that it became indistinguishable from daily life.

Le Chambon didn’t hide children; the village became the hiding place. Today, Le Chambon looks like any other small French village. Stone houses cluster around a modest church, and farms dot the surrounding hills. Tourists pass through in summer, hiking the mountain trails, unaware they’re walking paths that once served as escape routes for hunted children.

But if you know where to look, the memory remains. A small museum documents the conspiracy. Plaques mark the homes of key figures. And every year, on a cold morning in February, survivors and their descendants gather in the village square to remember. Some are in their 80s now, the last living witnesses to what happened here. They return to thank a place that saved their lives and to ensure that the story doesn’t die with them.

Because Le Chambon’s greatest fear isn’t being forgotten by the world; it’s being remembered as saints. The villagers never wanted to be exceptional; they wanted to be normal. And that’s precisely what makes their story so devastating.

A Call to Action

Here’s what the history books won’t tell you: Le Chambon succeeded because it rejected the premise that there were only two choices during the Holocaust—collaborate or resist violently. The village found a third way: nonviolent defiance at scale. They didn’t sabotage Nazi operations; they simply refused to participate in genocide.

And that refusal, multiplied across an entire community, proved more effective than any bomb or bullet. It’s a lesson that terrifies governments and inspires revolutionaries in equal measure. Because if one poor village in occupied France could save 3,000 lives without firing a shot, what does that say about every other place that claimed helplessness? What does it say about the millions who insisted they had no choice?

Le Chambon proved that choice always exists. And that’s a dangerous truth for those who profit from obedience. The children who survived Le Chambon carried the conspiracy into their own lives. They became teachers, doctors, activists, and artists. Many dedicated their careers to human rights work, refugee advocacy, and Holocaust education.

They married, had children of their own, and told their kids about the Protestant farmers who had hidden them in barns and taught them to milk cows. Those second-generation stories are now being passed to a third generation—grandchildren of survivors who never met the villagers but inherited their moral clarity.

In a world increasingly divided by nationalism, xenophobia, and the demonization of refugees, Le Chambon’s example has become more relevant, not less. Every time a government closes its borders to asylum seekers, every time a politician claims that protecting the vulnerable is too dangerous or too expensive, someone points to a small village on a French plateau and asks, “If they could do it with nothing, why can’t we?”

But here’s the uncomfortable truth that survivors themselves will tell you: Le Chambon was an anomaly. It shouldn’t have worked. The odds of success were microscopic. One informant with a grudge, one Gestapo officer willing to massacre an entire village as an example, one logistical collapse, and the whole network would have crumbled. Thousands would have died, and the world would have never known their names.

The villagers succeeded not because they had a perfect plan, but because they refused to abandon their principles even when failure seemed certain. That’s not a strategy; it’s a gamble. And most of the time throughout history, that gamble fails catastrophically. We remember Le Chambon because it’s the exception.

We must also remember the countless other places—the villages that tried to resist and were burned, the families that hid refugees and were executed, the networks that were betrayed and destroyed. Their courage was no less real. Their failure doesn’t diminish their decency. But it does remind us that goodness doesn’t guarantee survival. Sometimes evil wins.

And yet, Le Chambon endures not as a fairy tale with a perfect ending, but as proof that even in humanity’s darkest hour, some people refuse to let the darkness win. 3,000 children lived because 5,000 villagers decided that some lines cannot be crossed. No government ordered them to act. No army protected them. They simply saw children in danger and opened their doors.

That’s the story. That’s the secret they hid in plain sight. And now you know why it was almost erased. Because it’s a story that asks too much of us. It asks us to imagine what we would do if the knock came to our door. It asks whether we would risk everything for a stranger’s child.

And it refuses to let us believe that cowardice is ever the only option. Le Chambon didn’t just save 3,000 lives; it saved the idea that ordinary people armed with nothing but conscience can stand against empires. And that idea, more than any monument or museum, is the true weapon of the spirit that still echoes across the plateau.