German POWs Held in Minnesota Described It as HEAVEN

In the summer of 1944, as World War II raged on, a remarkable story of transformation unfolded in the heart of Minnesota. This is the story of Oberleutnant Hans Müller, a captured German tank gunner, and his fellow prisoners of war (POWs) who, instead of facing punishment, found themselves treated with unexpected kindness and dignity in a foreign land.

Captured in the Heat of Battle

On June 8, 1944, at 2:47 PM, Hans Müller stood in the cargo hold of a Liberty ship, crossing the Atlantic. Through a porthole, he watched the American coastline emerge from the fog. At just 23 years old, Müller had been a tank gunner in North Africa, only to be captured three days after D-Day in Normandy. For the two years prior, he had endured the harsh realities of war, sleeping atop his panzer in the desert and in muddy foxholes in France, surviving on meager rations.

As he and 847 other German POWs made their way to America, the atmosphere was thick with uncertainty. Many of the men expected punishment, having heard terrifying stories about American POW camps. Some believed they would be executed; others feared forced labor in remote areas like Alaska. Müller, however, had lost faith in any expectations, having learned to trust only what he could see and touch.

The Arrival in America

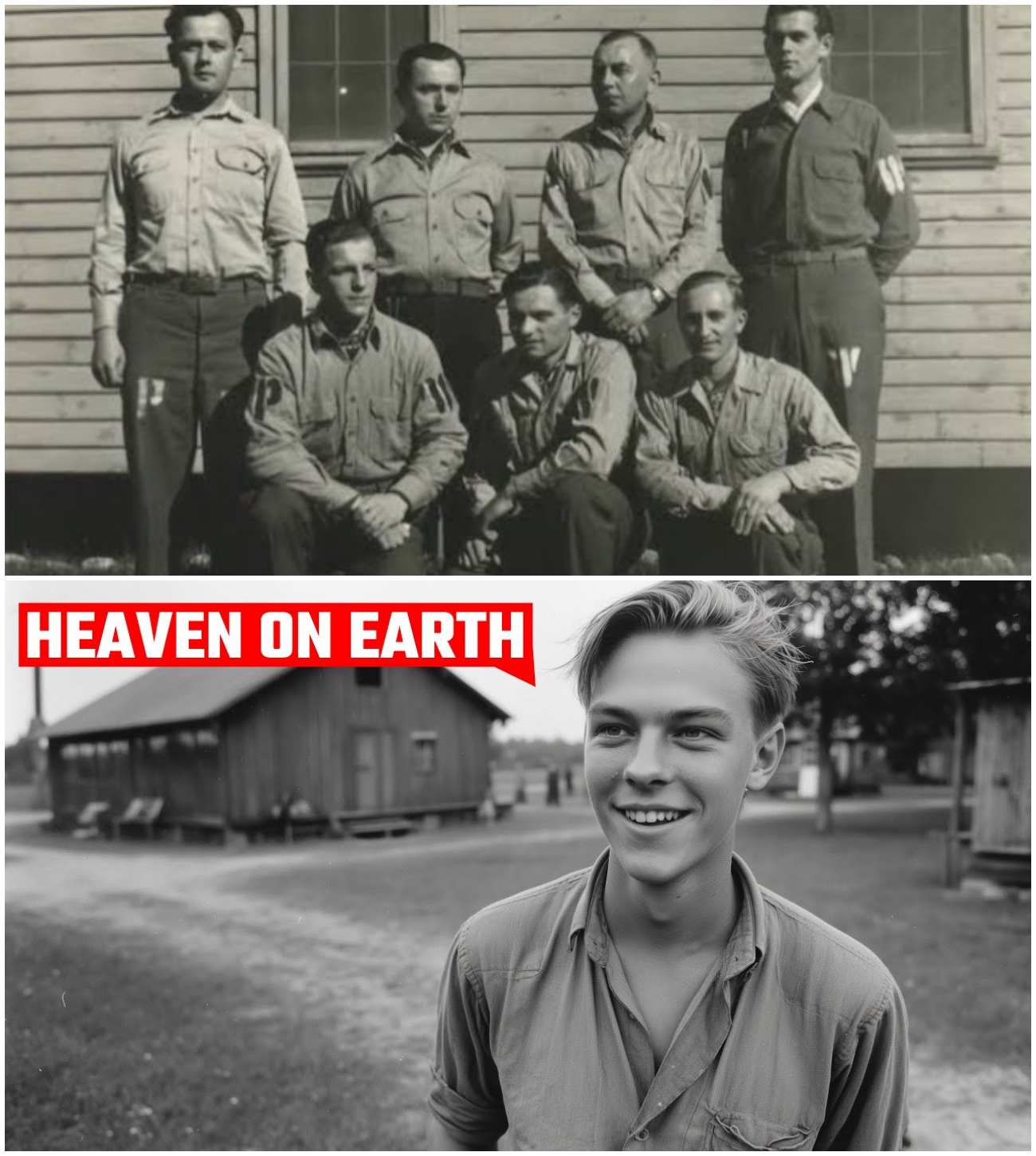

The ship docked in New York Harbor on June 11, 1944. As the prisoners were processed through Ellis Island, the reality of their situation began to shift. Instead of harsh treatment, they were greeted by American military police who searched them, photographed them, and issued them uniforms—olive drab with large “PW” letters stenciled on the back. Müller was astonished to find his uniform clean and new, a stark contrast to the tattered clothes he had worn for months.

During the processing, they were fed sandwiches with real meat and coffee with sugar. Müller savored each bite, still expecting the food to be taken away before he finished. To his surprise, an MP even offered him a second sandwich without being asked. It was a small act of kindness that marked the beginning of a profound transformation in his understanding of captivity.

The Journey to Minnesota

That night, Müller and 400 other POWs boarded a train heading west. Instead of the boxcars used to transport Soviet prisoners, they were in passenger cars with cushioned seats and windows that opened. An American guard walked through the car, distributing blankets. As Müller wrapped the wool blanket around himself, he felt a warmth he hadn’t experienced in years.

He fell asleep, exhausted, and woke up 16 hours later when the train stopped in Chicago. Breakfast was served: bread, butter, jam, and real coffee. As they traveled across the American landscape, the German prisoners began to share their thoughts. One prisoner, a former Luftwaffe mechanic named Schmidt, laughed, speculating that if the Americans fed them this well during transport, the camps must have actual beds and real toilets. Others remained skeptical, believing it was propaganda to fatten them up for photographs.

A New Life at the POW Camp

On June 14, 1944, Müller and the other prisoners arrived at a camp outside the town of Alona in north-central Minnesota. The camp had previously served as a Civilian Conservation Corps facility, featuring wooden barracks arranged in neat rows, a mess hall, a recreation building, and a small hospital. The entire camp was surrounded by a single barbed wire fence, more reminiscent of a cattle pen than a prison.

The camp commandant, Major Patterson, addressed the prisoners, explaining their rights under the Geneva Convention. They would work six days a week, receive pay at the rate of ten cents per hour in Camp Script, and have one day off. They would be housed in barracks with beds and bedding, receive three meals a day, and have access to medical care and recreational facilities.

Müller walked to his assigned barracks and found a steel-frame bed with a mattress, two blankets, and a pillow. He pressed down on the mattress, marveling at its softness. This was a far cry from the straw and bare boards he had endured in the past. That first meal at the camp was served at 6 PM, and Müller was astonished to find roast beef, mashed potatoes, green beans, bread, butter, and even a slice of apple pie on his tray.

A Taste of Humanity

As Müller sat down to eat, he calculated the calories on his tray. In one meal, he was consuming more than he had typically eaten in three days during the final months of fighting in Normandy. The contrast was overwhelming. As he watched his fellow prisoners, he noticed one, Hoffman, crying silently over his mashed potatoes. Müller understood the depth of his emotions; Hoffman had spent 13 months as a prisoner, first in North Africa and then in transit, before arriving in Minnesota.

The next morning, the work assignments began. At 5:30 AM, a whistle blew, and Müller dressed for breakfast, which consisted of pancakes, syrup, bacon, and coffee. After breakfast, the prisoners received their work assignments. Müller and 47 others were assigned to a vegetable farm owned by the Peterson family, located just 12 miles from the camp.

When they arrived at the farm, Mr. Peterson explained that they would be hoeing weeds in his 40-acre cabbage field. The work would continue until the entire field was completed, approximately three weeks. Peterson promised to provide water and a lunch break at noon, expecting the prisoners to work efficiently but not injure themselves.

Müller had never worked on a farm, having trained as a machinist before the war. However, he quickly adapted to the task, feeling the warmth of the Minnesota sun on his back as he hoed weeds. At 10:15, Mrs. Peterson appeared at the edge of the field with a large metal can, calling out in English, “Water break!” The guard translated, and the prisoners eagerly gathered for a refreshing drink.

Building Connections

During lunch breaks, the prisoners enjoyed sandwiches of ham and cheese on thick slices of bread, apples, and cookies. Müller found himself in disbelief at the abundance of food. Schmidt remarked that this was better than anything he had eaten during his time in the Luftwaffe. Another prisoner, Weiss, reflected on how his family in Bavaria had struggled to survive on potatoes and cabbage for two years, while he now sat in Minnesota eating ham sandwiches.

As the days turned into weeks, Müller and his fellow prisoners began to form connections with the Peterson family. They were no longer just enemies; they were individuals working side by side, sharing meals, and exchanging smiles. The transformation was palpable.

By the end of the three weeks, Müller had gained 11 pounds, a testament to the quality of food and the reduction of stress in his life. His body was responding positively to the nourishment. The prisoners enjoyed their new routine, which provided predictability and safety—an oasis compared to the chaos of war.

The Aftermath of War

On May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered. The announcement came over the camp loudspeakers, and while the American guards did not celebrate, they informed the prisoners that the war in Europe was over. The prisoners continued their work assignments until further notice, but the atmosphere had shifted. They were no longer just captives; they were part of a new reality.

In June, authorities announced that the German POWs would remain in America until transportation could be arranged to send them home. In July, new regulations were implemented, reducing the availability of beer and cigarettes in the camp store. The quality of food began to decline as complaints from American civilians about German prisoners eating well reached Congress.

Despite these changes, Müller remained grateful for the treatment he had received. He understood that the Americans were still adhering to the Geneva Convention, providing adequate nutrition and care. He had heard stories from prisoners who had been captured on the Eastern Front and later transferred to American custody through exchanges. Those men described Soviet camps where prisoners died by the thousands from starvation and disease.

A Decision to Stay

As the months passed, Müller received letters from his family in Stuttgart, detailing the destruction and hardship they faced. His father encouraged him to consider staying in America if opportunities arose. Müller wrestled with the decision: return to a war-torn Germany or build a new life in Minnesota.

In March 1946, after much contemplation, Müller approached Mr. Peterson and accepted his offer to help with the immigration process. He would stay in America, apply for immigration, and work on the Peterson farm. Peterson welcomed him with open arms, recognizing the potential for a new beginning.

The immigration application process took several months, during which Müller continued to work on the farm and improve his English. On December 17, 1946, he received notification of his immigration approval. He was now a legal immigrant to the United States, a former enemy soldier who had fought against American forces now authorized to live and work in America permanently.

A New Chapter

Müller married Margaret Hansen in June 1951, and they welcomed three children into their lives. He became a successful farmer, raising corn and soybeans on the land he purchased in 1949. As he reflected on his journey, he recognized the extraordinary path he had taken—from tank gunner to POW to farmer and eventually to an American citizen.

On April 12, 1952, Müller became an American citizen, reciting the oath of allegiance in a federal courthouse in Fort Dodge, Iowa. He had come full circle, standing before a judge who welcomed him into his new home. The mathematics of his journey seemed improbable, yet here he was, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit.

Legacy of Transformation

Hans Müller farmed in Minnesota for 43 years, raising his children and contributing to the community. He never returned to Germany, but he maintained correspondence with relatives in Stuttgart until his death in February 2011 at age 89. His funeral, held at the same Lutheran church where he had married Margaret, was attended by over 200 people—friends, neighbors, and former students who had learned from his experiences.

The pastor’s eulogy highlighted Müller’s journey from a soldier in a terrible war to a man who found mercy and compassion in an unexpected place. His life served as a powerful reminder that even in humanity’s darkest moments, grace is possible, and former enemies can become neighbors.

Hans Müller’s story is not just one of survival; it is a testament to the transformative power of kindness, understanding, and the ability to forge new paths in the aftermath of conflict. His legacy endures, reminding us that even in the wake of war, hope and humanity can prevail.