No One Would Touch the Crying Baby at the Funeral — Until the Quiet Apache Stepped Forward

.

.

No One Would Touch the Crying Baby at the Funeral — Until the Quiet Apache Stepped Forward

They buried Alma Jane just past noon, beneath the lone cottonwood that split the cemetery’s fence where her shadow used to fall every Sunday. The preacher said her name as if it were nothing more than dust. No one cried—not even her sister, who stood with arms folded and lips pressed tight as cracked leather.

But then, as the preacher’s voice faded, a sound rose from the earth. A cry, soft at first, then swelling into a wail that broke through the murmurs of wind and guilt. Every head turned toward the small bundle at the foot of the grave, wrapped in a faded blue shawl, its tiny fists trembling above its chest. Alma’s baby—born out of wedlock, father unknown, skin too dark for the town’s comfort.

No one moved. No one knelt. The preacher cleared his throat, offered another verse, and stepped back as if the child might bite. Alma had worked the bakery, swept the chapel steps, and never spoke of the man who’d given her that baby. Some whispered it was a railroad drifter, others a Comanche, but a few old wives said Apache—the quiet one who brought her firewood that winter and never came to town. Still, no one spoke his name.

Now, with Alma in the ground and the child in the dirt, the town waited. For what, they didn’t know—until hoofbeats crested the far rise, slow and deliberate. A tall figure rode down toward them, wrapped in a soft brown hide coat, braids touching his shoulders, eyes unreadable. He dismounted before the gate and walked the rest of the way, the crowd parting not out of respect but unease.

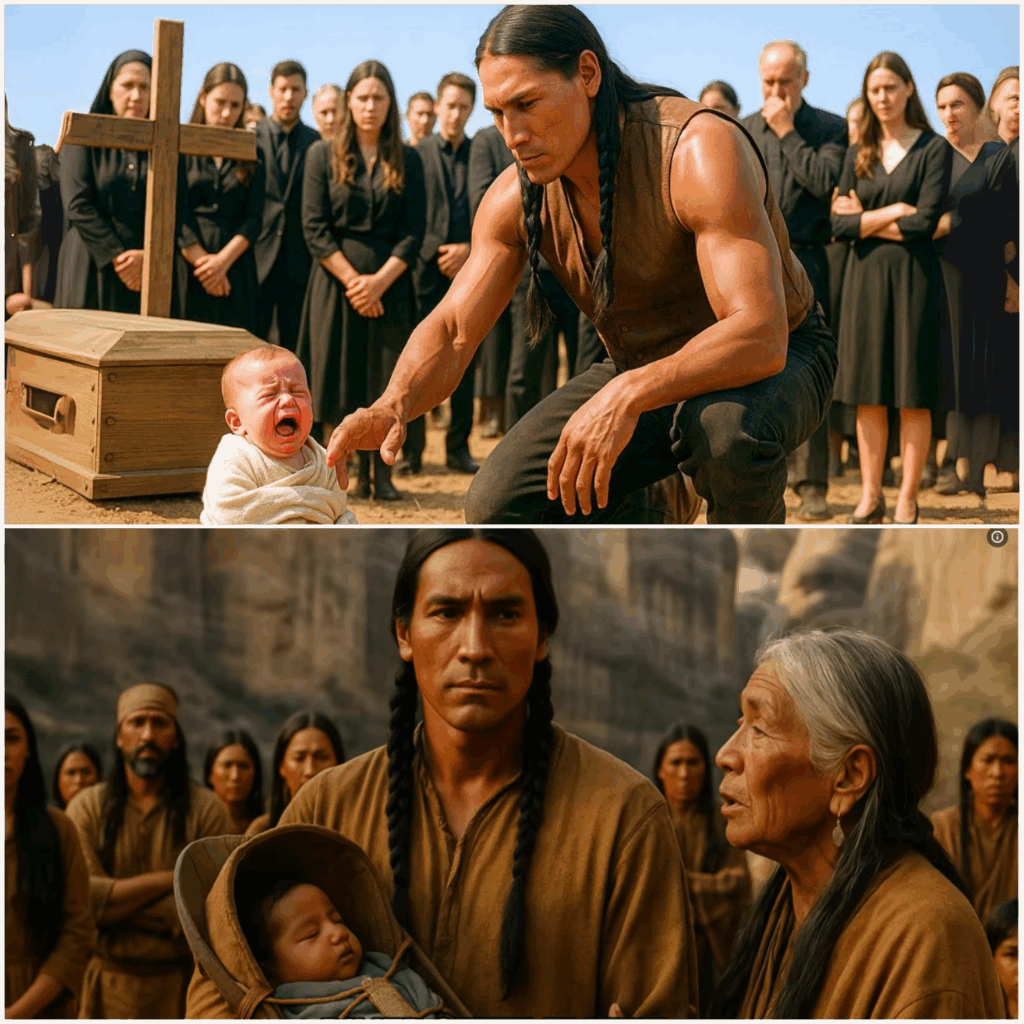

He didn’t speak, just looked at the preacher, then at the child, then at the mound of freshly turned earth. When he reached the baby, he knelt, rested a hand near her cheek, and whispered something in a language only the wind seemed to understand. The baby quieted. A few women gasped. One man took off his hat, but the Apache didn’t rise. He opened a pouch from his belt and pulled out a small woven charm—cedar and white thread—and placed it over the baby’s heart. Then, with impossible tenderness, he lifted the child, shawl and all, and pressed her to his chest. He didn’t ask. He didn’t explain. And not a soul had the right to stop him.

The sheriff stepped forward, hesitated, and then froze, as if some deeper law had already passed judgment. The Apache looked to the grave one last time, nodded once, then walked back to his horse. Only as he mounted did the wind carry his words, spoken in quiet English, shaped like grief and honor: “Her name was Alma. I promised.” And with that, he rode off, child in arms, church behind, leaving only the sound of soft breath and stunned silence in his wake.

Somewhere deep in the preacher’s throat, a prayer faltered. The baby had stopped crying, but the town had only just begun to feel the weight of its shame.

The town talked about it for days, but never in the open. Whispers curled like smoke between pews and porch rails, drifting into coffee cups and behind half-closed shutters. No one said his name because no one knew it, but they spoke of him all the same. That Apache, the one from Canyon Pass. Alma’s ghost.

Sheriff Weller sat longer than usual on his bench outside the jailhouse, rubbing his wedding ring like it could answer for him. He’d seen a hundred men carry guns, drag horses, throw punches. But never had he seen a man carry a child like that—not even white men with their own flesh and blood.

“You think he’ll bring it back?” the blacksmith muttered one morning, hammer paused mid-swing.

“It?” his apprentice asked, and that single word echoed harder than the anvil’s strike.

The widow who ran the bakery put out one less loaf each day, and Alma’s name was never spoken behind that counter again. But at night, the children asked questions their parents couldn’t answer. Who was he? Why did he take the baby? What did the baby do? And always the parents said something between a lie and a fear: “It wasn’t our place,” or “He won’t come back.” But behind those words was a deeper truth. They hadn’t wanted the baby either. They’d stood at that grave like mourners, but they’d left the child in the dirt as if grief didn’t stick to brown skin.

Only one person dared speak differently. Hattie May, the preacher’s blind daughter, who’d once heard Alma sing lullabies to that child from her porch two houses down. “He wasn’t there to steal,” Hattie said one evening, fingers tracing the hem of her shawl. “He was there to keep a promise none of y’all would have kept.” No one answered her. No one dared. And still, no one went looking—not to the canyon, not past the river fork, not where the cottonwoods thinned and the cliffs breathed stories. But the baby was still talked about like a ghost. Not gone, but unfinished.

Every time the wind rustled through the trees near Alma’s grave, a few townsfolk flinched as if it carried footsteps back toward them. Sheriff Weller kept the birth record locked in his desk drawer, unsigned and still damp at the corner where Alma’s last breath had stained it. Female, unnamed, it read. But it wasn’t true anymore. The Apache had whispered something to that child, something the wind had caught. A name. A name no one had written down. And somehow, that made it more real than anything else they’d ever recorded.

The town had chosen silence over guilt, pride over mercy. But a child had been claimed, and a man they’d never dared to know had ridden away with more grace than any of them could muster. Now every silence in town sounded like a question. Would he raise her to hate them? Would she come back one day with his eyes and her mother’s voice and ask what they had done? No one knew. No one wanted to know.

But some nights, when the wind shifted just right, a few of them swore they could still hear it. Not a cry anymore, but laughter. Small, soft, and carried by hooves, fading westward into the canyon’s deep breath.

Deep in the canyon beyond the river fork, where the air grew still and the stars hung low like guardian eyes, the Apache laid the child down beside the fire. He had not spoken since leaving the grave, not even to the wind. But now, in the hush of dusk, he knelt before the woven cedar cradleboard he had tied from strips of bark and old sinew, and placed the child within it, as if swaddling a sacred story.

Her eyes, wide, dark, and searching, found his without fear. She did not cry, not once. He watched her for a long time, then whispered the name he had chosen. “Tyanita,” he said softly, his voice like riverstone warmed by sun. “Little beaver, strong in the stream.” It was the name Alma had once told him in secret, when her hands were red from baking and her eyes full of dreams she’d never speak aloud to her church. She had chosen it before the baby was born, but never written it—never dared to say it where ears might twist it. Only to him, one night beneath a sky so quiet even the crickets listened.

Now the name belonged to the child as surely as the stars belonged to the sky. He placed the cedar charm on her chest—the one he had woven with Alma that same night, each thread a promise. She clutched it in her small hand like she’d always known it. Across the fire, his horse snorted softly and lay down, knowing they would not travel tonight. The canyon held them in its arms. Old rock sheltering new life.

In the silence, he remembered the first time he saw Alma dragging a broken wagon wheel up a hill with no one stopping to help. He had watched from the treeline, then stepped out only when her hands gave way. She had not flinched when she saw him.

“You’re not what they say,” she’d said calmly.

He had not answered. He never did. But he had stayed close after that. Never touching, never speaking too long, just bringing firewood, setting snares near her door, watching from the ridge when storms came in. She’d called him a ghost once, then later a friend. But always there was a distance—not one of fear, but of truth. He did not belong in her world, and she would never survive in his.

When her belly began to show, he vanished for moons—not out of shame, but knowing the weight she would carry. He thought she might hate him. Instead, she left a folded note in the stump he always checked. One line: I’ll raise her with your quiet.

But now Alma was gone and the baby slept where the fire danced on her cheeks. He didn’t know if he could raise a child. He didn’t know if his people would even let him. But he knew one thing as certain as breath: he would not leave her alone. Not in this world, not in any other.

As the flames licked the sky and the night wrapped around them, he placed his palm gently on her back. “You are not shame,” he said to her, and to Alma, and to himself. “You are the beginning.” And the canyon listened.

By morning, smoke from the Apache’s fire had risen into the high stone arches, and with it word had traveled—not by telegram or trail, but by birdsong, hoofprint, and instinct. When he rode toward the lower camps of his people, Tyanita wrapped snug against his chest in the cradleboard, he felt the silence ripple ahead of him. Children stopped chasing each other near the riverbend. Elders straightened. A few women turned their backs. No one spoke. Not even the dogs barked.

He dismounted slowly, keeping his eyes forward, his steps grounded. The headwoman, old Sali, approached with the slow weight of someone who had buried too many truths. Her eyes found the child first, and in them flickered memory. Not surprise—she did not touch the baby.

“You bring a settler’s child,” she said in Apache, low and hard. “One born in shame.”

He did not flinch. “One born in silence,” he replied, “promised to her mother by a man who said nothing and did everything.”

Sali stepped closer, close enough to smell the cedar smoke still clinging to the child’s shawl. “And now you think silence will raise her? That our ways will stretch to cover your sin?”

Around them, a ring of villagers formed, some angry, some afraid, all waiting.

The Apache looked down at Tyanita, her eyelids fluttering, her small hand still wrapped around the charm. “No,” he said. “I ask nothing from the tribe, only a place where the wind is kind and the water runs clean.”

A man in the crowd scoffed. Another muttered, “He brings a seed that is not of us.” But then Sali raised her hand, and all voices fell.

“Let him speak,” she said, “and then let the stone decide.”

At dusk they gathered in the canyon’s heart, where three great stones stood, each marked by fire, wind, and burial—the place of old decisions. There he placed the cradleboard between them.

“She has no tongue to defend herself,” he said to the circle. “But I have eyes to watch her, arms to carry her, and a heart that already knows her name.”

One by one, those who had once known Alma—the traitor’s daughter, the girl who asked too many questions, the one who’d vanished from the river settlement—began to soften. A woman stepped forward and placed a small basket of milkroot by the cradle, another a folded cloth. No one cheered; no one smiled. But when the headwoman spoke again, her voice had shifted.

“The stones say nothing,” Sali said. “But the child is warm, and no child should be cold.”

That night, he was given a tent on the far edge of camp—not as punishment, but as space. Tyanita slept between furs while he carved her a rattle from riverbark. He did not celebrate. He did not weep. But for the first time in years, he sang—not loudly, but enough for the child to stir. And in her half sleep, she smiled.

In the morning, he would start teaching her to walk with soft feet. But for now, the canyon had not rejected her. The tribe had not turned away. And he had not failed. Beneath the stone sky, two breaths rose together, one old, one new, and neither was alone.

Far beyond the canyon, past the ridges where vultures circled and stagecoaches left dust like fading trails of memory, a hand reached for an old leather ledger buried beneath the floorboards of Widow Barnes’s apothecary. She hadn’t meant to find it, was only sweeping out the moths from the back corner when her broom struck loose the plank. But when she saw the initials burned into the cover—A.J.—her fingers trembled.

Alma Jane.

Inside, yellowed pages revealed careful notes in Alma’s handwriting: herbal tinctures, pie recipes, midwifing instructions, and at the very back, a single entry written in smaller, shakier script: Due in spring. Name: Tyanita. Father unknown to town, known to me, soul quiet as snow.

Widow Barnes sat back against the wall, heart tight in her chest. She remembered Alma’s shy smile, the way she lingered too long over cedar oil, how she once asked what salve could make a scar feel less like memory. The ledger didn’t lie. The girl had loved—not loosely, not foolishly, but in silence, as many women had, too afraid to speak the name of a man the world wouldn’t accept.

Barnes closed the book slowly. She had been the one to deliver Alma’s baby, had wrapped the tiny girl while Alma bled into the straw and whispered only, “Tell no one. But if he comes, give him this.” The old woman had waited, but no one came. Not until the day of the funeral, when word reached her that an Apache had taken the baby from the grave.

Now, days later, she realized Alma’s faith had not been misplaced. He had come, and he had known her name.

With a grim breath, she packed the ledger into her satchel and saddled her mule. She would go to Sheriff Weller—not to ask questions, but to give answers.

Meanwhile, in the canyon, Tyanita held her new rattle in both hands, shaking it with a seriousness that made her guardian smile. He had no need to teach her joy. It came uninvited, like rain over firewood.

He taught her other things. How to press her palm to the ground and feel hoofbeats. How to touch water and know its current. How to listen when no one spoke. The others watched from a distance. A few brought gifts now: marrow bone, a carved doll, a bead necklace left on stones at the edge of their lodge. He never asked who left them, but always nodded once toward the sky, as if thanking someone above who still believed.

One evening, as smoke curled from their fire, the headwoman came again.

“There’s word,” she said. “A white woman carries a book with the child’s name.”

He stiffened, unsure. “Is she coming here?”

Sali shook her head. “Not yet. But she carries no anger, only memory.”

Then she crouched before the child, letting the girl touch her braids. “She will walk two paths,” the elder said. “Let her feet learn both without shame.”

That night, as the moon hung low and the canyon rocks turned silver, he looked down at Tyanita and wondered what Alma would say now, seeing her daughter alive, warm, held in the heart of a people who once would have turned away. He did not know what lay ahead, but in that moment he whispered again her name, and she answered with a quiet coo. The wind stirred like a page turning, and far away a mule carried a ledger home.

Sheriff Weller had seen his fair share of odd arrivals, busted wagons, runaway brides, snake oil men with silver tongues, but nothing rattled him quite like Widow Barnes walking into his office, dusty satchel in hand, eyes fixed and dry like she’d outlived the right to cry. She said nothing at first, just laid the leather-bound ledger on his desk and nodded once. He opened it without protest, thumbing past the neat entries until he reached the final page. When he read Alma’s scrawl, that one quiet sentence about the father, the name Tyanita, and the truth she never dared to say aloud, something in his chest twisted.

He leaned back in his chair, letting the silence stretch. “Why now?” he asked finally.

Widow Barnes sat down across from him, smoothing her skirt with the slow dignity of someone who’d already counted the cost. “Because the baby wasn’t abandoned,” she said. “She was entrusted. And that Apache, he didn’t steal her. He fulfilled what none of us were brave enough to do.”

Weller stared at the name again. Tyanita. The weight of his own failure pressed down like a badge turned to lead. “They’ll ask what I did,” he murmured. “What I allowed.”

Barnes nodded. “So tell them you saw a man do what no one else would.”

He closed the ledger slowly and rubbed the bridge of his nose. “Where is she now?”

“Some say the canyon,” she replied. “But she’s safer than she ever was in this town.”

Weller stood and walked to the window, staring out at the dusty street where children chased chickens and mothers hung laundry like sins on a line. He’d watched Alma pass that window every Sunday, hair tucked into a bonnet, back straight despite whispers. He’d never asked her why she never looked up. Now he knew—because looking up would have meant seeing all the faces who didn’t care.

Behind him, Barnes rose to leave. “You still the law in this town, Sheriff?” she asked.

“I try to be.”

“Then you best start acting like it.”

When she left, he didn’t move for a long time. Just stared at the place on his desk where the ledger had sat, the ghost of Alma’s handwriting still etched behind his eyes. That night, he opened the town record book and did what no one had done. He wrote in the birth ledger, “Tyanita, female. Mother, Alma Jane. Father, unknown, claimed by guardian at Alma’s request.” He paused, then added, “Seen last in the arms of a man who did not speak, but who did not have to.”

Meanwhile, the canyon stars watched over Tyanita as she laughed in her sleep, the rattle slipping from her hands. Her guardian placed a hide blanket over her and stepped outside the lodge. He looked to the stars, wondering if Alma could see her now. Behind him, he didn’t hear Sali approach.

“The world remembers through paper,” she said. “But we remember through wind.”

He nodded, not needing to speak.

“Still,” she continued. “Sometimes it helps for the paper to tell the wind’s truth.”

Far off, a night bird cried. Sali placed a carved feather at the base of the lodge. “When the white woman comes,” she added, “let her see not what we took, but what we kept alive.”

He watched her leave, then turned back to the lodge, where the child now murmured a word he did not teach her.

“Mama,” she whispered, and the canyon stilled.

He sat beside her through the night, not to protect, but to witness—not to teach, but to remember. For in that moment, between ledger and lullaby, the child had found her voice.

.

play video: