Arrogant Therapist Tried to Psychoanalyze Me – I Analyzed His Bank Account

The Therapist Who Tried to Analyze the Judge

.

.

.

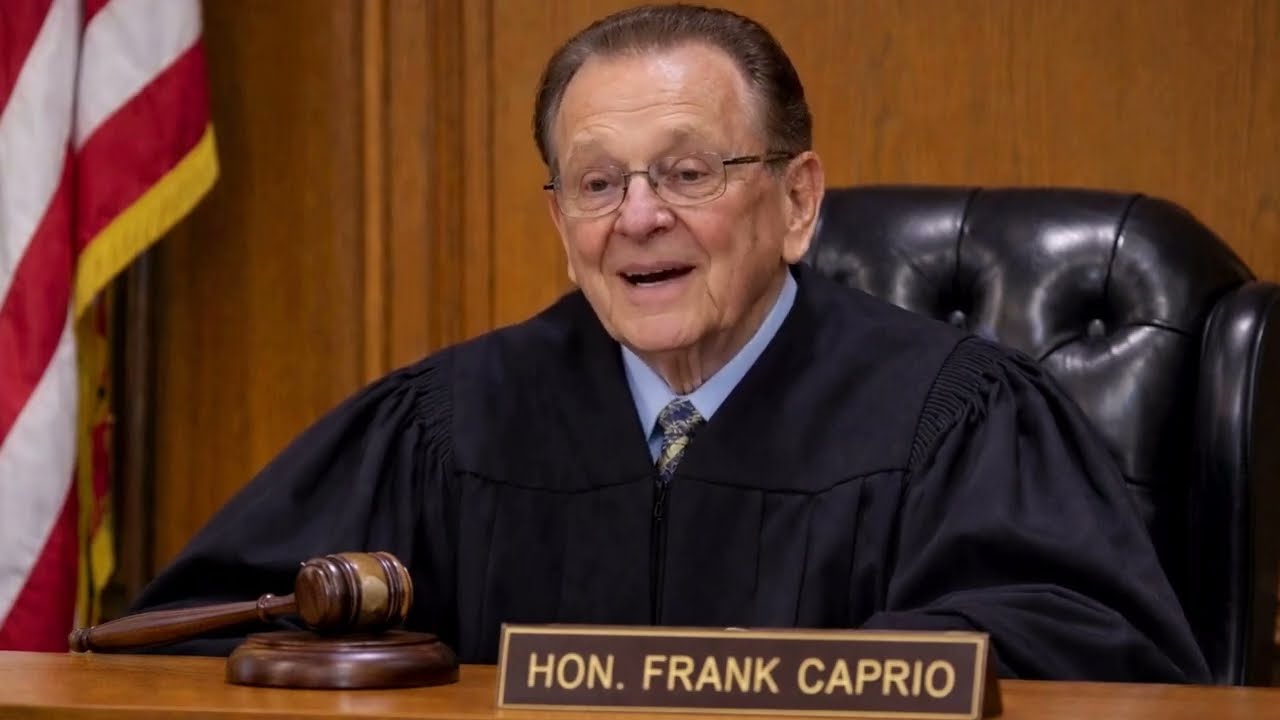

In forty years on the bench, I thought I had seen every kind of arrogance human beings could bring into a courtroom. I was wrong.

It happened on a quiet Friday morning in Providence, mid-October, the kind of New England autumn day that makes you grateful just to be alive. The leaves were turning, the air was crisp, and I had walked into court feeling calm, steady, ready to serve.

The morning docket was routine—minor traffic violations, small disputes, people admitting mistakes, asking for mercy. Most days, justice is quiet like that. Honest. Human.

Then, around eleven o’clock, the bailiff called a name, and my peaceful morning ended.

A man walked in—late thirties, maybe early forties—well dressed, confident, carrying a leather portfolio. But it wasn’t his clothes that caught my attention. It was the way he looked at the courtroom.

Not nervous.

Not respectful.

He studied the room like a scientist observing test subjects. Detached. Analytical. Superior.

The charge was serious: reckless driving through a school zone.

Fifty-five miles per hour.

A twenty-five zone.

During school dismissal.

Children had jumped back. A crossing guard had waved frantically. Parents had screamed. The entire incident was caught on the school’s security camera.

I looked at the file, then at him.

“Sir,” I said, “you’re charged with reckless driving in a school zone. Do you understand the charges?”

He tilted his head slightly, as if considering the psychological depth of my question.

“Your Honor,” he replied calmly, “I understand the legal framework. But I believe it’s important we discuss the psychological pressures and contextual factors that contributed to my behavior.”

That was the first warning sign.

I asked him a simple question.

“Do you dispute that you were driving fifty-five in a twenty-five?”

“I don’t dispute the speed,” he said, “but as a licensed therapist, I understand that behavior exists on a spectrum. I had just finished an emotionally draining session with a client in crisis. I was not in an optimal mental state.”

He was using therapy language to excuse endangering children.

When I told him that many people have stressful days and still don’t speed past elementary schools, he leaned forward and said something I will never forget.

“Your Honor, I’m sensing some resistance here. That often happens when authority feels challenged. It’s a defense mechanism.”

He psychoanalyzed me—while standing accused of reckless driving.

The courtroom froze.

For forty years, no one had ever done that.

When the prosecutor played the security footage—children jumping back, parents pulling kids out of the way—the man watched with clinical detachment. No remorse. No horror.

When the video ended, he said, “I understand how that appears, but video doesn’t capture my internal cognitive processing.”

That’s when I thought of another case.

Earlier that week, a woman named Linda stood before me. A single mother. A diner worker. She had been speeding to pick up her sick child. When I asked her what happened, she cried.

“I was wrong,” she said. “I could have hurt someone. I’m so ashamed.”

She didn’t excuse herself. She didn’t analyze herself.

She took responsibility.

I reduced her fine.

That’s what remorse looks like.

So I asked the therapist, “In your practice, when a client hurts someone, what do you tell them?”

He smiled, pleased.

“We explore the root causes. We create self-compassion. We avoid shame.”

“And the person who was hurt?” I asked. “Do they matter?”

He hesitated.

I pressed him again. “Why haven’t you said you’re sorry?”

Finally, he answered.

“I’m sorry the situation occurred.”

Not sorry I did it.

Sorry it happened.

A non-apology.

That’s when clarity hit me.

This wasn’t about psychology.

This was about ego.

A man so invested in being the expert that he couldn’t admit he was wrong.

I told him plainly:

“You’ve analyzed everyone but yourself. You endangered children, and you refuse to say you’re sorry.”

Then I delivered my ruling.

The standard fine was $800.

I raised it to $2,000.

And that wasn’t all.

I sentenced him to 60 hours of community service as a crossing guard—at the very school where he had sped through.

Every morning.

Every afternoon.

For an entire semester.

He objected. His lawyer protested. He cited research.

I answered simply:

“You don’t need more time in your head. You need time in the real world.”

When court ended, he finally whispered the words he had avoided all morning.

“I’m sorry.”

Three months later, I received a letter from the school principal.

She wrote that at first, the man was stiff and uncomfortable. Then he learned the children’s names. Then they began to trust him. Hug him.

One day, a little girl he had nearly hit asked him if he remembered driving too fast.

He knelt down and said, “Yes. And I’m so sorry.”

She hugged him and said, “I forgive you.”

The principal said the experience changed him. He became a better therapist. More honest. More accountable. More human.

Months later, I saw him again.

“You taught me the hardest lesson of my life,” he said. “I stopped hiding behind expertise and learned how to be humble.”

That’s why I still do this work.

Not to punish—but to transform.

Because intelligence without humility is dangerous.

And sometimes, the most powerful therapy isn’t analysis.

It’s accountability.