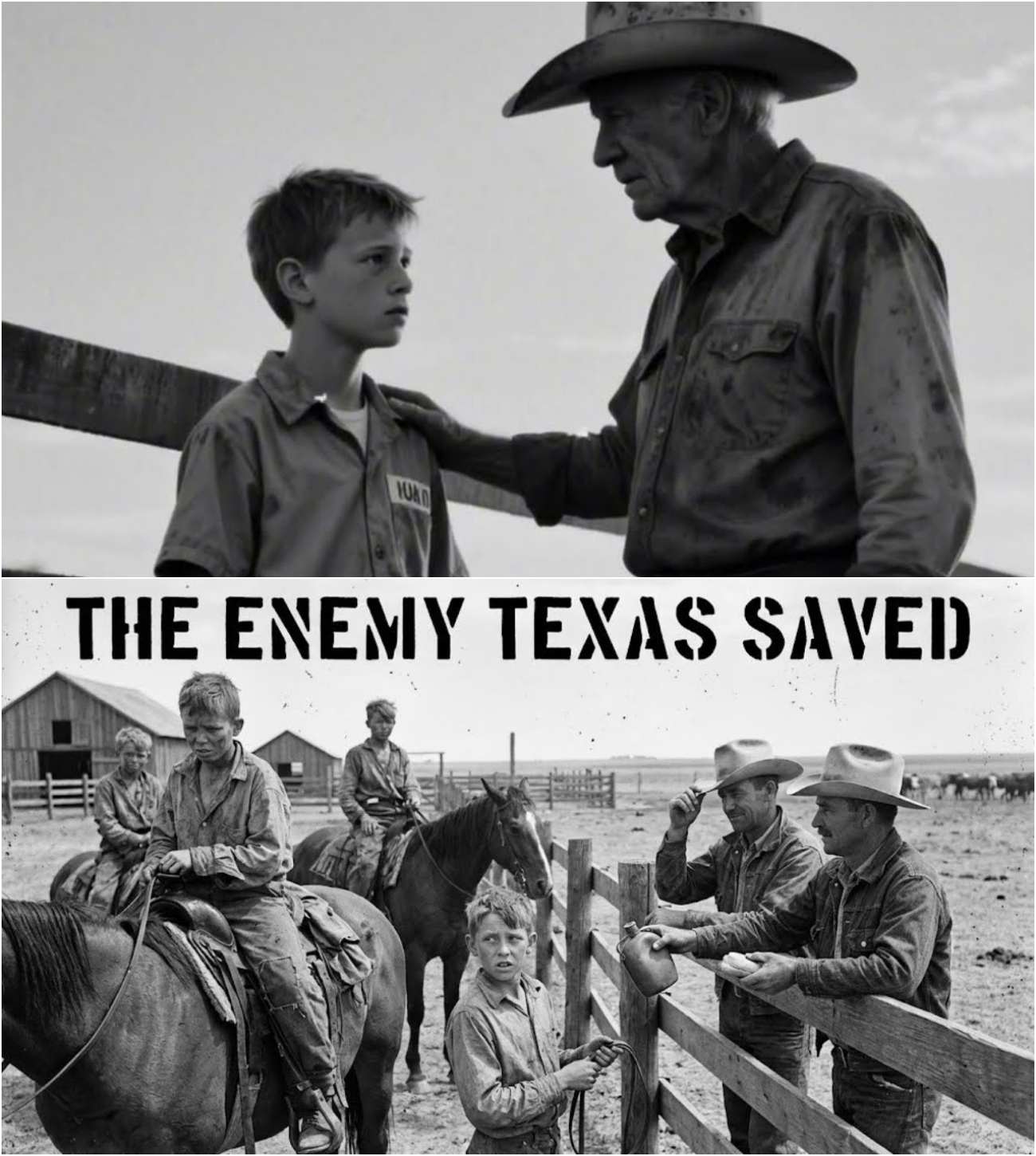

German Child Soldiers Were Sent to a Texas Ranch — The Cowboys Treated Them Like Brothers

July 14, 1944. The sun beat down mercilessly on the cracked earth of a cattle ranch outside Hebbronville, Texas. Dust swirled in the air as a truck rumbled through the ranch gate, carrying with it a group of young boys—17 German prisoners of war, aged between 14 and 16. Their hands still bore blisters from the rigorous training they had endured in Hitler Youth camps, and now they found themselves 4,000 miles from home, terrified of what awaited them.

The boys had been fed stories—Nazi propaganda that painted American cowboys as lawless killers who dragged captives behind horses. As they climbed down from the truck, they were met by the ranch foreman, a weathered man named Samuel Hardwick, who stood waiting, bow-legged and sunbaked like the Texas landscape. He didn’t raise his voice or brandish a weapon; instead, he simply nodded toward the barn and said one word: “Work.”

In that moment, the boys realized everything they had been taught in Berlin was a lie. The war had reached a strange intersection by the summer of 1944. Germany’s eastern front was collapsing, and the Allies had landed at Normandy just six weeks earlier. Yet across America, nearly 400,000 German prisoners of war lived in camps scattered from California to Virginia. The U.S. faced a paradox: millions of American men were fighting overseas while farms and ranches sat empty, crops rotting in the fields. Labor shortages threatened the food supply that fueled the war machine.

Washington made a calculated decision: put the prisoners to work. But these weren’t hardened Wehrmacht veterans; the boys sent to Texas ranches were remnants of the Volkssturm and Hitler Youth, drafted in Germany’s desperate final levy. Some had fired rifles, but most had only marched in formation and sung patriotic songs. They had surrendered in France or North Africa, often without a fight, and now they stood on American soil, property of a nation they had been trained to hate.

The Geneva Conventions required captives to be treated humanely, yet the convention said nothing about what happened when prisoners met cowboys. The ranch outside Hebbronville covered 12,000 acres of scrub land, with cattle grazing in loose herds across terrain too rough for mechanized farming. Hardwick, a third-generation rancher, had lost his two sons to the Pacific theater and needed hands. The army needed labor details. The arrangement was practical, not political.

The foreman assigned to oversee the boys was a man called Rusty, whose real name was Russell Kowalski, the son of Polish immigrants. He had cowboyed for 40 years across three states, spoke little, worked hard, and judged men by their blisters, not their birthplace. When the boys arrived, Rusty saw fear in their eyes, a look he had seen before on colts separated from their mothers or ranch hands fresh from the city. Fear he knew could be gentled or sharpened. His choice would define what happened next.

The First Days

The first morning, Rusty led the boys to the tack room. Saddles hung on wooden racks, leather worn smooth by decades of use. He pointed to a pile of blankets and bridles. The boys stared, unsure what to do. None had ridden horses; their Nazi youth training emphasized marching, not ranching. One boy, a thin 15-year-old named Thomas, reached for a saddle that weighed 40 pounds. He struggled, face reddening, trying to lift it alone.

Rusty watched for a moment, then stepped forward—not with anger, but with a simple demonstration. He showed Thomas how to brace the weight against his hip, how to let his legs carry what his arms couldn’t. That gesture was small, but it changed everything. Thomas expected punishment for weakness; instead, he received instruction.

Over the following days, Rusty repeated this pattern. When a boy fumbled a rope, Rusty retied the knot slowly, letting him watch. When another fell from a horse, Rusty helped him up and put him back in the saddle. There were no beatings, no humiliation—just the steady, patient rhythm of teaching. The boys had known only hierarchy and discipline; orders shouted, mistakes punished. This was different. This was mentorship.

By the third week, something unexpected emerged: the boys began to laugh. At first, it was nervous chuckles when someone dropped a lasso, but soon it grew into genuine laughter around the evening campfire. Rusty and the other ranch hands treated them like green recruits, not enemies. They marked failed rope throws with good-natured ribbing and showed the boys how to roll cigarettes from tobacco and newspaper, how to play cards, how to sing trail songs under stars so bright they seemed within reach.

One evening, a boy named Otto pulled a harmonica from his pocket. He had carried it through France, hidden in his boot during capture. He played a slow, mournful melody, something from the Rhine Valley. The cowboys listened in silence. When he finished, one of the hands, a man named Jimmy, picked up a guitar and played a Texas ballad about lost love and open plains. The two melodies couldn’t have been more different, yet somehow around that fire, they fit together.

The Transformation

The work was hard—harder than anything the boys had known. Herding cattle across rough terrain demanded strength, focus, and resilience. Barbed wire tore at their hands, dust choked their lungs, and the Texas heat pressed down like a physical weight. But the work was also honest. No ideology, no propaganda—just a task, a tool, and the satisfaction of completing it. For boys raised on promises of conquest and glory, this simplicity was revolutionary.

They weren’t fighting for a cause; they were fixing a fence. And somehow, that mattered more. Rusty noticed the transformation. Thomas, the boy who had struggled with the saddle, now handled horses with quiet confidence. Otto, the harmonica player, could rope a calf faster than some of the ranch hands. Even the youngest, a boy named Emil who barely spoke English, had learned to anticipate the cattle’s movements.

They were becoming cowboys—not in costume, but in spirit. The swagger of Hitler Youth had given way to something steadier—a kind of masculinity built on competence, not conquest. But the change wasn’t just in the boys. The ranch hands, too, felt something shift. Jimmy, the guitar player, had a brother fighting in Europe. He had hated Germans with a burning certainty. Yet watching these boys struggle and grow, that hate became harder to hold. They weren’t monsters; they were kids—kids who had been fed lies and sent to die.

One night, after Otto played his harmonica, Jimmy told him about his brother, about the letters that had stopped coming. Otto listened. He didn’t apologize for the war, but he shared his own losses—his father killed in a bombing raid, his hometown reduced to rubble. The conversation didn’t erase the war, but it humanized both sides.

By August, the ranch operated like a well-oiled machine. The boys had become indispensable. They knew the cattle, the land, the rhythms of ranch life better than some lifelong hands. Hardwick told Rusty he’d never had a better crew. But everyone knew it couldn’t last. The war in Europe was nearing its end. Soon the boys would be sent home or to other camps or kept as prisoners indefinitely. The future was uncertain.

So they focused on the present—each day’s work, each evening’s campfire, each moment of normalcy in an abnormal world. In September, the camp commandant visited the ranch. He’d heard reports of fraternization, of prisoners and cowboys growing too friendly. He reminded Hardwick and Rusty that these were enemy combatants, not ranch hands. The Geneva Conventions required work, but not brotherhood.

The visit cast a shadow over the ranch. The boys felt the shift. The easy laughter grew strained. The cowboys kept more distance. For a week, the ranch felt cold despite the Texas heat. Then Rusty made a decision. One morning, he gathered the boys and the ranch hands together. He spoke plainly. The war would end someday. Until then, they had work to do.

He didn’t say they were brothers; he didn’t have to. He simply handed Thomas a rope and told him to teach the new calf-roping technique to Jimmy. That gesture, small and defiant, restored the balance. The commandant’s rules would be followed, but the spirit of the ranch couldn’t be regulated. They weren’t just prisoners; they were part of something larger.

The End of an Era

By January 1945, the ranch operated at peak efficiency. The boys had become indispensable. They knew the cattle, the land, the rhythms of ranch life better than some lifelong hands. Hardwick told Rusty he’d never had a better crew. But everyone knew it couldn’t last. The war in Europe was collapsing. News reached the ranch in fragments—cities burning, armies surrendering. The boys received it with numb silence.

They’d known this was coming, but hearing it made it real. Everything they’d believed in was ash. Thomas asked Rusty what would happen to them now. Rusty didn’t lie. He said he didn’t know. But whatever came, they’d face it with the skills and values they’d learned. No one could take that away.

In February, Germany began its final collapse. News reached the ranch by radio. The cowboys removed their hats in respect. The boys watched, uncertain how to react. Rusty explained that in America, you could honor a leader, even if you’d once been his enemy. Respect wasn’t about politics; it was about recognizing integrity.

The boys absorbed this lesson like all the others, quietly, deeply. When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the ranch gathered around the radio. The announcement came through static and crackling interference. The war in Europe was over. The boys sat in stunned silence. They’d known it was coming, but hearing it made it real.

Thomas cried. Otto stared at the ground. Emil whispered a prayer in German. The cowboys gave them space to grieve because they understood. The boys weren’t crying for Hitler or the Nazi regime; they were crying for everything they’d lost—their childhoods, their families, their country as they’d known it.

The days following surrender felt surreal. The boys still worked the ranch, but the weight had shifted. They were no longer prisoners of a nation at war; they were prisoners waiting for a war to finish processing them. Bureaucracy moved slowly. Weeks passed with no word on their fate. Rusty kept them busy; work was the best distraction, and the ranch still needed hands.

In June, the orders finally came. The boys would be sent to a larger processing camp, then eventually repatriated to Germany. The news hit harder than anyone expected. The ranch had become home. Texas had become familiar. The cowboys had become family. Leaving felt like exile.

The night before departure, Hardwick hosted a final meal—steaks grilled over mesquite, beans, cornbread, and peach cobbler. The boys ate slowly, savoring every bite. After dinner, Rusty stood. He didn’t make a speech; he simply shook each boy’s hand, looked them in the eye, and told them they’d always have a place on the ranch if they ever returned.

The morning of departure arrived too quickly. The boys packed their few belongings, dressing in the same clothes they had arrived in, though now the uniforms hung loose on frames hardened by ranch work. They climbed into the same truck that had brought them, but they weren’t the same boys.

Thomas looked back at the ranch, memorizing the details—the barn where he’d learned to saddle a horse, the corral where he’d roped his first calf, the bunkhouse where he’d laughed harder than he ever had in Germany. As the truck rolled through the gate, Otto played his harmonica one last time, a slow, mournful melody. The cowboys stood watching until the dust settled and the sound faded. They didn’t speak; there was nothing left to say.

They’d done something rare in wartime. They’d chosen humanity over hatred, mentorship over exploitation, and in doing so, they’d changed 17 lives forever. The boys returned to a Germany they barely recognized—cities in ruins, families scattered or gone, a world they had fought for no longer existing. But they carried something with them: a memory of Texas sunsets, of cowboys who taught instead of punished, of a different kind of strength.

Thomas eventually immigrated back to America, working ranches across the Southwest, never forgetting the skills Rusty taught him. Otto rebuilt his hometown, bringing American pragmatism to German efficiency. Emil found his mother alive and spent the rest of his life farming, teaching his children the values he’d learned on a Texas ranch.

Rusty continued cowboying until his body gave out. He never spoke much about the German boys; when asked, he’d shrug and say they were just hands, good hands. But those who knew him understood. He’d made a choice that summer of 1944—to see boys instead of enemies, to teach instead of punish. And that choice rippled through decades.

The ranch continued for another generation before being sold to developers. The bunkhouse where the boys slept was torn down, the corral where they learned to rope paved over. Yet the story remained, passed down through families, remembered in letters and faded photographs—a reminder that even in war, humanity finds a way.

The cowboys didn’t try to break the boys’ spirits; they redirected them. They showed them that true strength comes from building, not destroying, from teaching, not dominating, from respect earned through competence, not fear imposed through violence. It was a simple philosophy, but in the summer of 1944, on a dusty ranch outside Hebbronville, it changed 17 lives.

And through them, it changed the world just a little bit. The cowboys didn’t just save the boys from a life of hatred; they taught them how to live with compassion, how to treat others with respect, and how to forge bonds that transcended borders and ideologies. In a time of conflict, they found a way to build something beautiful—a legacy of kindness that would outlast the war itself.