“Get Him Out of Here!” – Why Eisenhower FIRED General Fredendall

In April 1943, a scene of celebration unfolded at the train station in Memphis, Tennessee. Flags waved, bands played patriotic marches, and the crowd buzzed with excitement as they awaited the arrival of a hero—Lieutenant General Lloyd R. Fredendall. He was hailed as the man who led the American landings at Oran during Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. To the public, he was a conqueror, a fighting general who had stared down the Nazis and returned home to train the next generation of soldiers.

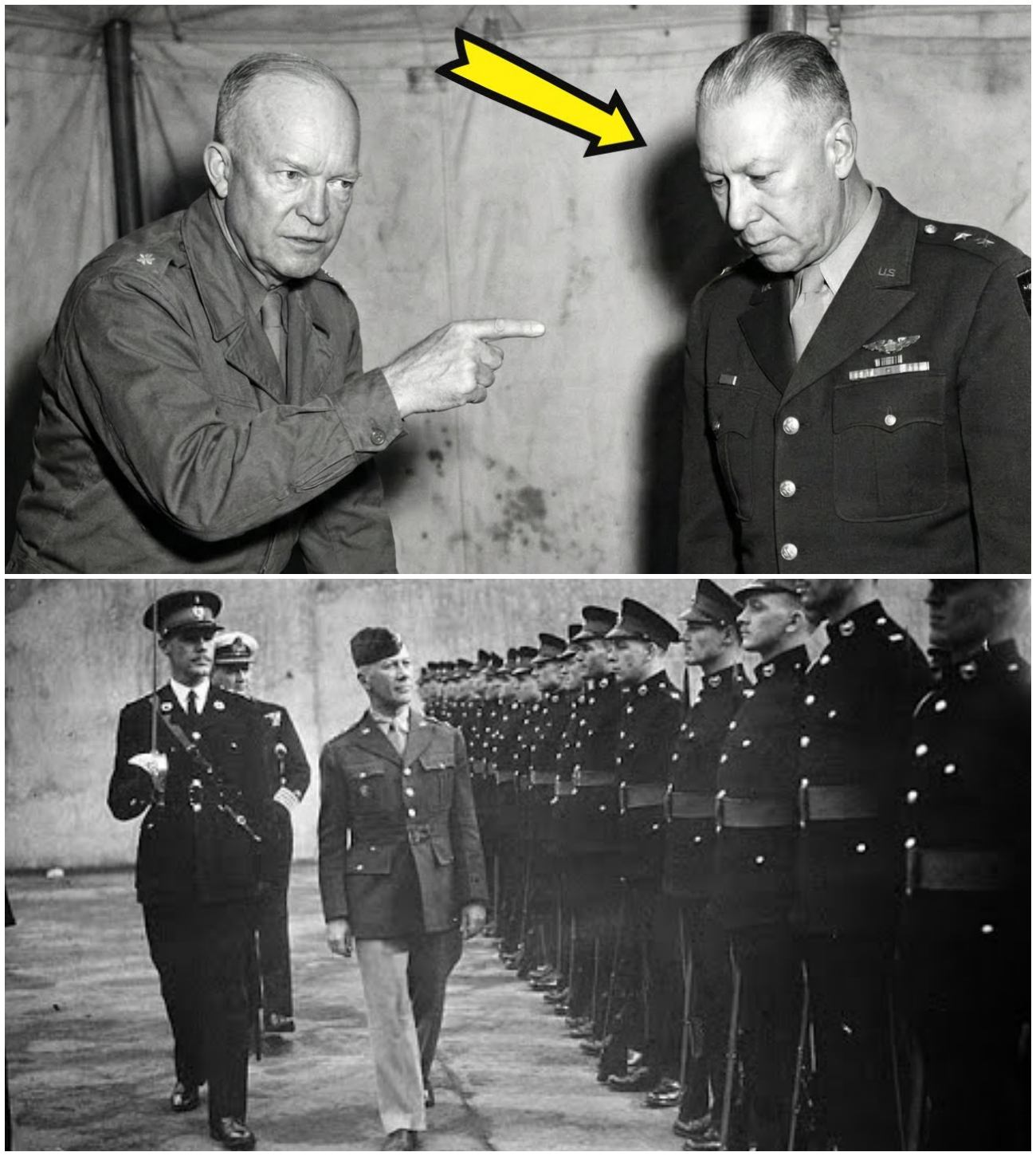

However, thousands of miles away in Tunisia, a different story was unfolding. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, was grappling with the reality of Fredendall’s leadership. While the cheers echoed in Memphis, Eisenhower was increasingly frustrated with Fredendall, who had proven to be one of the most incompetent generals in American military history. This is the story of how a man once celebrated as a hero became a liability, leading to his dismissal from command during one of the critical moments of World War II.

A Hero’s Welcome

As Fredendall stepped off the train, he carried himself with an air of confidence, accepting the accolades and the promotion to Lieutenant General. He was a compact man with a swagger, embodying the image of an American hero. The newspapers painted him as a triumphant leader, but behind the facade lay a different truth. Fredendall had not returned home as a hero; he had been fired by Eisenhower to prevent further disaster.

In Tunisia, the situation was dire. Fredendall’s leadership had resulted in chaos and confusion, with American soldiers suffering heavy casualties under his command. While he basked in the glory of his perceived success, the reality was that he had failed his men, leading them to unnecessary slaughter at the Battle of Kasserine Pass.

The Illusion of Competence

Fredendall’s rise to power can be attributed to appearances rather than actual competence. He looked and sounded like a general, with a commanding presence that impressed his superiors, including General George Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff. Marshall described Fredendall as a man with determination, and during pre-war maneuvers, he performed well in administrative tasks and training exercises.

When Operation Torch was being planned, Marshall placed Fredendall at the top of the list for command. Eisenhower, trusting Marshall’s judgment, welcomed Fredendall into his command structure. However, the cracks in Fredendall’s leadership began to show almost immediately.

The Cracks Begin to Show

Fredendall’s disdain for his allies was evident. He harbored a deep-seated loathing for the British and French forces, which was particularly problematic in a coalition war where cooperation was essential. His contempt for British officers led to a refusal to communicate effectively, undermining the unity needed to face a common enemy.

Moreover, Fredendall ruled by fear and exclusion. He demanded obedience rather than collaboration, often bypassing his subordinate commanders to issue orders directly to their troops. His treatment of Major General Orlando Ward, commander of the First Armored Division, exemplified this toxic leadership style. Fredendall viewed Ward as weak and bullied him, creating a toxic atmosphere of mistrust and resentment among his officers.

The Bunker Mentality

As the Americans advanced into Tunisia, Fredendall made a fateful decision that would seal his fate as a commander. He chose to establish his headquarters in a secluded ravine known as Speedy Valley, located 70 miles behind the front lines. This decision was unprecedented; most generals commanded from forward positions to maintain a connection with their troops and the battlefield.

Instead of leading from the front, Fredendall opted for safety. He ordered hundreds of engineers to construct an elaborate underground bunker, complete with living quarters, offices, and even anti-aircraft defenses. While his men suffered in the mud and rain at the front, Fredendall built a fortress for himself, oblivious to the realities of war.

The Disaster at Kasserine Pass

The turning point came on February 14, 1943, during the Battle of Kasserine Pass. Fredendall’s forces were unprepared and poorly led, with units scattered and vulnerable. As the German Panzer divisions, under the command of General Erwin Rommel, launched their attack, Fredendall remained in his bunker, issuing orders based on outdated intelligence and a lack of situational awareness.

Despite warnings from his subordinate commanders, Fredendall refused to adapt his strategy. He issued orders that led to disastrous consequences, including a futile counterattack that resulted in the loss of dozens of American tanks. The chaos escalated as American troops retreated in panic, abandoning their positions and equipment.

The retreat from Kasserine Pass was a humiliating defeat for the U.S. Army, marking the first major battle against the Germans. Fredendall’s failure to lead effectively resulted in a catastrophic loss of life and morale.

The Reckoning

In the aftermath of the defeat, Eisenhower recognized the need for decisive action. He sent Major General Ernest Harmon to assess the situation and take command if necessary. Harmon arrived at Speedy Valley to find Fredendall in a state of disarray, more concerned with his own safety than the welfare of his troops.

Harmon quickly realized that Fredendall was not fit for command. He reported back to Eisenhower, stating unequivocally that Fredendall was “no damn good” and needed to be removed from his position. Eisenhower, faced with the reality of Fredendall’s incompetence, made the difficult decision to fire him.

The Aftermath

Fredendall’s dismissal was handled quietly, as Eisenhower feared the public relations fallout of removing a general after a significant defeat. Instead of facing court martial or demotion, Fredendall was reassigned to a training command, where he could serve without the pressure of combat.

When he returned to the United States, he was treated as a hero. The media celebrated his achievements, and he was promoted to Lieutenant General, commanding the Second Army responsible for training new recruits. While Fredendall proved competent in training, he never saw combat again, living out his days in relative obscurity until his death in 1963.

A Lesson in Leadership

The story of Lloyd R. Fredendall serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of leadership based on appearances rather than actual performance. Eisenhower learned a critical lesson from the experience: a general’s reputation means little if it is not backed by effective leadership and results on the battlefield.

After Fredendall, Eisenhower became more ruthless in his command. He understood that the lives of American soldiers were more important than the careers of incompetent generals. The story of Speedy Valley and the Kasserine Pass became a warning for future leaders, emphasizing the importance of accountability and the need for generals who would lead from the front.

Conclusion

The legacy of Lloyd R. Fredendall is one of failure and missed opportunity. His story is a reminder that leadership requires more than just a polished exterior; it demands competence, courage, and a commitment to the troops on the front lines. As the U.S. Army moved forward in World War II, the lessons learned from Fredendall’s disastrous command would shape the future of military leadership for generations to come. The bunkers in Speedy Valley may be empty now, but they stand as a monument to the wrong way to lead—a stark reminder of the consequences of complacency and incompetence in the face of war.