Overview:

The Olmec lived along the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the modern-day Mexican states of Tabasco and Veracruz.

The Olmec society lasted from about 1600 BCE to around 350 BCE, when environmental factors made their villages unlivable.

The Olmec are probably best known for the statues they carved: 20 ton stone heads, quarried and carved to commemorate their rulers.

The name Olmec is an Aztec word meaning the rubber people; the Olmec made and traded rubber throughout Mesoamerica.

Who were the Olmec?

The Olmec were the first major civilization in Mexico. They lived in the tropical lowlands on the Gulf of Mexico in the present-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. The name Olmec is a Nahuatl—the Aztec language—word; it means the rubber people. The Olmec might have been the first people to figure out how to convert latex of the rubber tree into something that could be shaped, cured, and hardened. Because the Olmec did not have much writing beyond a handful of carved glyphs—symbols—that survived, we don’t know what name the Olmec people gave themselves.

Appearing around 1600 BCE, the Olmec were among the first Mesoamerican complex societies, and their culture influenced many later civilizations, like the Maya. The Olmec are known for the immense stone heads they carved from a volcanic rock called basalt. Archaeological evidence also suggests that they originated the Mesoamerican practices of the Mesoamerican Ballgame—a popular game in the pre-Columbian Americas played with balls made from solid rubber—and that they may have practiced ritual bloodletting.

Trade and village life

There are no written records of Olmec commerce, beliefs, or customs, but from the archaeological evidence, it appears they were not economically confined. In fact, Olmec artifacts have been found across Mesoamerica, indicating that there were extensive interregional trade routes. The presence of artifacts made from jade, a semiprecious green stone; obsidian, a glassy, black volcanic rock; and other stones provides evidence for trade with peoples outside the Gulf Coast of Mexico: the jade came from what is today the Mexican state of Oaxaca and the country of Guatemala to the south; the obsidian came from the Mexican highlands, to the north. The Olmec period saw a significant increase in the length of trade routes, the variety of goods, and the sources of traded items.

A map of the Olmec heartland, the Tuxtla Mountains, and part of the Gulf of Mexico. The yellow dots represent Olmec settlements, and the red dots represent archaeological finds. These Spanish place names are modern; we don’t know what the Olmec names for these places were.

A map of the Olmec heartland. The yellow dots represent Olmec settlements, and the red dots represent archaeological finds. These Spanish place names are modern; we don’t know what the Olmec names for these places were. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Trading helped the Olmec build their urban centers of San Lorenzo and La Venta. These cities, however, were used predominantly for ceremonial purposes and elite activity; most people lived in small villages. Individual homes had a lean-to—sort of like a garage shed—and a storage pit for storing root vegetables nearby. They also likely had gardens in which the Olmec would grow medicinal herbs and small crops, like sunflowers.

A photograph of the Great Pyramid in La Venta on a partly cloudy day. The pyramid takes up most of the image and there is a small tree with green leaves on the left-hand side. Mostly dead, brown grass covers the pyramid but there are patches of green at the bottom.

Great Pyramid in La Venta, Tabasco. Image courtesy Boundless.

Most agriculture took place outside of the villages in fields cleared using slash-and-burn techniques. The Olmec likely grew crops such as maize, beans, squash, manioc, sweet potatoes, and cotton.

Religion

There are no direct written accounts of Olmec beliefs, but their notable artwork provide clues about their life and religion.

Photograph of a stone carving. A chief wears an elaborate headdress and carries a weapon. His face has been worn down over time so features are not discernible.

Surviving art, like this relief of a king or chief found in La Venta, help provide clues about how Olmec society functioned. Image courtesy Boundless.

There were eight different androgynous—possessing male and female characteristics—Olmec deities, each with its own distinct characteristics. For example, the Bird Monster was depicted as a harpy eagle associated with rulership. The Olmec Dragon was shown with flame eyebrows, a bulbous nose, and bifurcated tongue. Deities often represented a natural element and included the following:

The Maize deity

The Rain Spirit or Were-Jaguar

The Fish or Shark Monster

Religious activities regarding these deities probably included the elite rulers, shamans, and possibly a priest class making offerings at religious sites in La Venta and San Lorenzo.

Art

The Olmec culture was defined and unified by a specific art style. Crafted in a variety of materials—jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone, which is an archaeologist’s term for carved, green-colored minerals—much Olmec art is naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic—human-shaped—creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning. Common motifs include downturned mouths and cleft heads, both of which are seen in representations of were-jaguars and the rain deity.

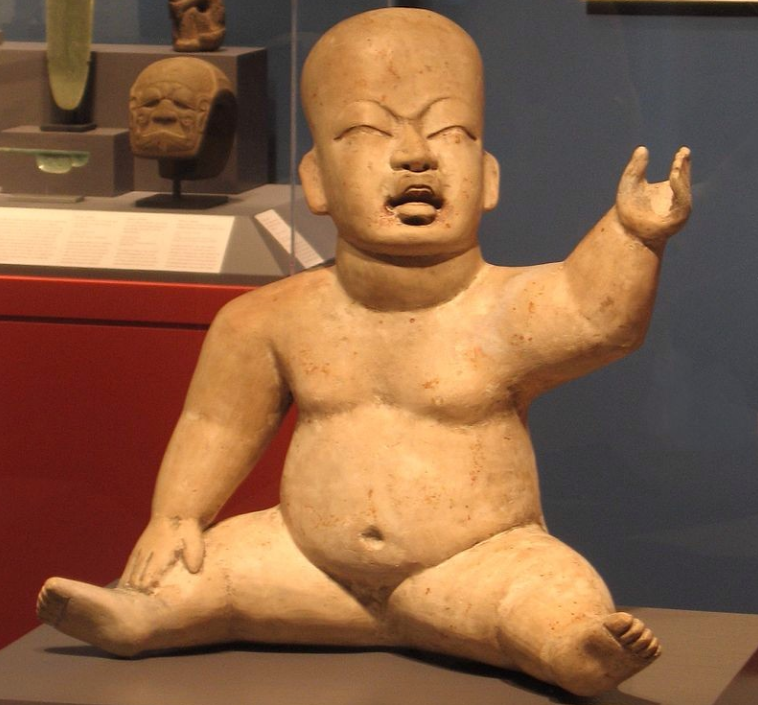

Photograph of a realistic ceramic baby figurine. The child is nude, with its eyes shut and furrowed brow, appearing to cry. It is seated and reaches one arm up. Its legs are splayed out.

Olmec hollow baby figurine. Realistic ceramic objects, such as this portrayal of an infant, illustrate the highly skilled artistic style of the Olmec culture. Image courtesy Boundless.

Olmec colossal heads

The most striking art left behind by this culture are the Olmec colossal—very big—heads. Seventeen monumental stone representations of human heads sculpted from large basalt boulders have been unearthed in the region to date. The heads date from at least before 900 BCE and are a distinctive feature of the Olmec civilization. All portray mature men with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly crossed eyes. However, none of the heads are alike, and each boasts a unique headdress, which suggests they represent specific individuals.

The Olmec brought these boulders from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. Given that the extremely large slabs of stone used in their production were transported over large distances, requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, it is thought that the monuments represent portraits of powerful individual Olmec rulers, perhaps carved to commemorate their deaths. The heads were arranged in either lines or groups at major Olmec centers, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to the sites remain uncertain.

Photograph of an Olmec colossal head. There is a headdress carved onto the head and its eyes, nose and lips are prominent while its ears are not visible. The head is made of stone and is placed outdoors with palm fronds in the background.

This sculpture, which stands almost eight feet tall and weighs about 24 tons, is typical of the colossal heads of the Olmec. It’s now housed in the Parque-Museum La Venta, in Villahermosa, the capital of the Mexican state of Tabasco. Image courtesy Boundless.

The end of the Olmecs

The Olmec population declined sharply between 400 and 350 BCE, though it is unclear why. Archaeologists speculate that the depopulation was caused by environmental changes, specifically by the silting-up of rivers, which choked off the water supply.

Another theory for the considerable population drop proposes relocation of settlements due to increased volcanic activity as the cause rather than extinction. Volcanic eruptions during the Early, Late, and Terminal Formative periods would have blanketed the lands with ash and forced the Olmec to move their settlements.

What do you think?

What do the colossal heads of the Olmec tell us about how their society was organized?

Given that the Olmec worshiped anthropomorphic deities, do you think they believed their rulers were human beings?

What kind of ecological disaster would have to take place in order to make your home unlivable?