German Child Soldiers in Oklahoma Refused to Leave America After the War Ended

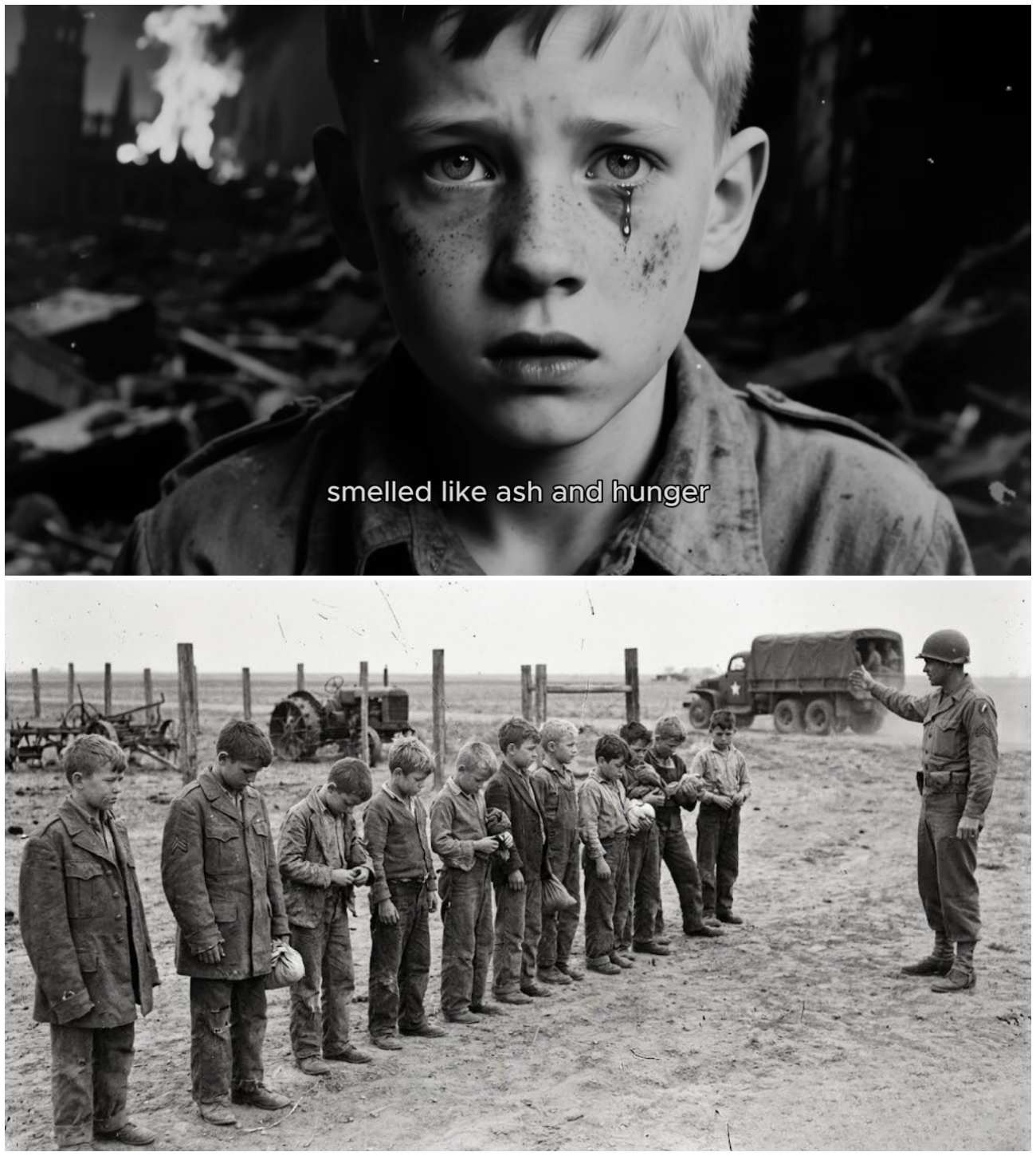

On June 8, 1945, the world was beginning to breathe a sigh of relief as the horrors of World War II came to an end. But for 15-year-old Klaus Becker, a German child soldier, the end of the war brought a different kind of fear—fear of freedom. Standing at the chain-link fence of Camp Gruber, Oklahoma, Klaus gripped the metal tightly, his knuckles turning white. He was supposed to be going home, but the thought of returning to a war-torn Germany filled him with dread.

A Boy Caught in the Crossfire

Klaus had been conscripted into the German army in December 1944, just months before the war’s conclusion. His father had been killed in an air raid, and his older brother had perished at Stalingrad. Now, with his mother missing and his hometown of Hamburg reduced to rubble, Klaus faced a bleak future. He had spent the last few months in a uniform that was too large for him, fighting a war he barely understood, and now he found himself behind barbed wire in a foreign land.

As he stood there, a guard walked by, boots crunching on the gravel. Klaus didn’t turn; he was frozen in place, grappling with the reality that returning to Germany meant facing a life of ash and hunger. Here in Oklahoma, he had food, safety, and a semblance of normalcy—a future that didn’t smell like destruction.

The Journey to Camp Gruber

Klaus and the other boys, known as “Hitler’s children,” were among the youngest prisoners of war ever held on U.S. soil. Most of them were between 13 and 16 years old, having been forced into service during the final months of the war. They had fought in the Battle of the Bulge and manned anti-aircraft guns in Berlin. When they surrendered to American forces, they were still children, confused and terrified.

The U.S. Army was unsure how to handle these young soldiers. They couldn’t be tried as combatants, yet they couldn’t simply be released either. Many had no homes to return to, no families waiting for them. As a result, they were sent to camps across the American Midwest, with Camp Gruber becoming home to one of the largest groups of these young prisoners.

Life at Camp Gruber

At Camp Gruber, Klaus and over 200 other German boys lived in wooden barracks and attended makeshift schools run by American officers and German immigrants. Slowly, the camp began to offer them something they had not experienced in a long time: healing. Klaus had arrived at the camp in the winter of 1945, and the change in environment was stark. The prairie stretched endlessly in every direction, devoid of the destruction that marked their homeland.

Colonel William Hastings, the camp commander, had served in the Great War and understood the toll of conflict. He ordered his officers to treat the boys with kindness, not as enemies. “These kids didn’t start this war,” he said. “They won’t end it by rotting in a camp.” This philosophy was not universally accepted, but Hastings remained resolute. The camp began to function as a place of learning, where the boys could regain their childhoods.

A New Kind of Education

Dr. Friedrich Lang, a German professor who had fled Berlin in 1938, was hired to teach the boys. He introduced subjects like history, mathematics, and English, but he also emphasized critical thinking. He encouraged them to question the propaganda they had been fed and to confront the realities of their situation.

Klaus remembered the day Dr. Lang discussed the concentration camps and the Holocaust. Initially, he resisted the information, labeling it as propaganda. But Dr. Lang’s calm demeanor and insistence on truth forced Klaus to grapple with the lies he had been raised to believe. That night, he lay awake in his bunk, reflecting on the stories of pride and glory he had heard about Germany. He began to wonder how much of it had been a lie.

As spring approached, the boys settled into a routine. They attended classes, participated in chores, and played soccer on a dirt field. The Americans even set up a small library stocked with German and English books. Klaus spent hours reading, discovering authors like Mark Twain and Jack London, and he began to envision a life beyond the war.

The End of the War and Uncertain Futures

On May 8, 1945, the announcement came over the loudspeakers: Germany had surrendered unconditionally. The boys gathered in the mess hall to hear the news. Some wept, while others sat in stunned silence. Klaus felt a mix of emotions—relief, confusion, and fear. The war was over, but what would happen to them now?

Rumors circulated about their fate. Some boys believed they would be sent to work camps in France, while others hoped they might be adopted by American families. As the days passed, Klaus began to dread the thought of being sent back to Germany. He imagined standing in the ruins of his hometown, searching for his mother, and starting over in a country that had lost everything.

One evening, Klaus approached Dr. Lang. “What if I don’t want to leave?” he asked. Dr. Lang understood the weight of Klaus’s words. “You’re a prisoner of war,” he replied gently. “You don’t get to choose.” But Klaus felt differently. “There’s nothing to rebuild. My city is gone. My family is gone. What am I going home to?”

The Fight for a New Home

By June 1945, nearly 40 of the boys at Camp Gruber expressed a desire to remain in America. Some wanted to finish their education, while others simply didn’t want to face the devastation waiting for them back home. They wrote letters to the camp commander, petitioning for asylum. The American authorities were baffled; the Geneva Convention required the repatriation of all prisoners of war, but these boys were children caught in an unprecedented situation.

Churches and civic groups in Oklahoma offered to sponsor some of the boys, but the army remained firm. Orders were orders. Klaus felt a sense of hopelessness as he learned that repatriation would begin in two weeks. The next morning, he returned to the fence, gripping the wire tightly as he gazed out at the prairie.

A guard named Corporal Miller approached him. “You okay, kid?” he asked. Klaus didn’t respond. “Look, I know it’s hard, but you’ll be all right. Germany’s going to need guys like you.” Klaus finally looked at him. “What if I don’t want to go?” he asked. Miller hesitated before replying, “Doesn’t matter what you want. It’s what has to happen.”

The Departure

As July approached, the boys at Camp Gruber grew quieter. They packed their few belongings and said goodbye to the teachers who had tried to show them a different world. Klaus was in the last group to leave. On his final night, he walked to the fence one last time, watching the sun set over the prairie. He thought about his mother and wondered if she was still alive.

Dr. Lang found him there. “You ready?” he asked. Klaus didn’t answer. “You know,” Dr. Lang said, “I left Germany because I had to. You’re leaving because you have to. But maybe one day you’ll come back here because you want to, and that will mean something.” Klaus nodded, though he didn’t believe it.

The next morning, the trucks rolled out, and Klaus watched through the rear window as Camp Gruber disappeared into the distance. He felt as if he were leaving the only safe place he had ever known. The ship that carried them back to Germany, the SS Marine Raven, was crowded and cold. The crossing took twelve days, and when they finally arrived at Bremerhaven, the port was a wasteland.

Klaus stepped off the ship onto German soil for the first time in seven months. He felt nothing—no relief, no joy, just emptiness. Processed by British authorities, he received a travel pass to Hamburg. The train ride took six hours, and as he looked out the cracked windows at the destroyed countryside, he felt a deep sense of loss.

Finding Home Again

When he reached Hamburg, he barely recognized it. Entire neighborhoods were gone, and the streets he used to walk were now paths through rubble. He found the address where his family’s apartment had been, but it was just a pile of bricks. He stood there, staring at the ruins, when a woman walking past stopped and asked if he was looking for someone.

When he told her his mother’s name, she shook her head. “I don’t know her, but you can check the refugee lists at the church.” Klaus went to the church and scanned the lists for an hour. He found his grandmother, living in a displaced persons camp near Lübeck. The next day, he took a train there.

When he arrived, his grandmother didn’t recognize him at first. He had left as a boy and returned as something else. But when he told her who he was, she wept, holding him tightly. He shared his story about Oklahoma, about the school, about the fence. After he finished, she looked at him with hollow eyes and said, “You should have stayed.”

Klaus spent the next year trying to rebuild his life. He worked odd jobs, cleared rubble, and attended night school. Slowly, he began to carve out a new existence, but he never stopped thinking about Oklahoma. In 1947, he applied for a visa to return to the United States, but it was denied. He applied again in 1949 and was denied once more.

A New Beginning

In 1952, the rules changed. West Germany was rebuilding, and relations with America were warming. Klaus applied a third time, and this time, his application was approved. He sailed back to America in the spring of 1953, at the age of 22, settling in Tulsa, less than 50 miles from Camp Gruber. He got a job in a factory, learned English, and married a local girl named Mary. They had two children.

Every year on June 8th, Klaus drove out to the site where Camp Gruber had once stood. The barracks were long gone, and the fence had been torn down, but he stood there anyway, remembering the boy he had been and the man he had become. He was not alone; of the 200 child soldiers who passed through Camp Gruber, at least 30 eventually returned to the United States, quietly building lives and families.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Survival

Klaus Becker died in Tulsa in 1998 at the age of 67. His funeral was small and quiet, attended by family, friends, and neighbors who knew him as a gentle man with a soft accent. To most, he was simply a husband, father, and co-worker, living an unremarkable American life. After the funeral, his son sorted through Klaus’s belongings and found a photograph tucked away in his father’s wallet.

The image was simple—a chain-link fence stretching across an empty prairie, dividing the foreground from the horizon. On the back of the photograph were three words written in Klaus’s steady hand: “Where I belonged.”

This story of Klaus Becker and the other German child soldiers at Camp Gruber serves as a poignant reminder of the complexities of war and the resilience of the human spirit. It challenges us to consider the lives of those caught in the crossfire, to recognize their humanity, and to understand that sometimes home is not defined by geography, but by the safety and acceptance we find in unexpected places.