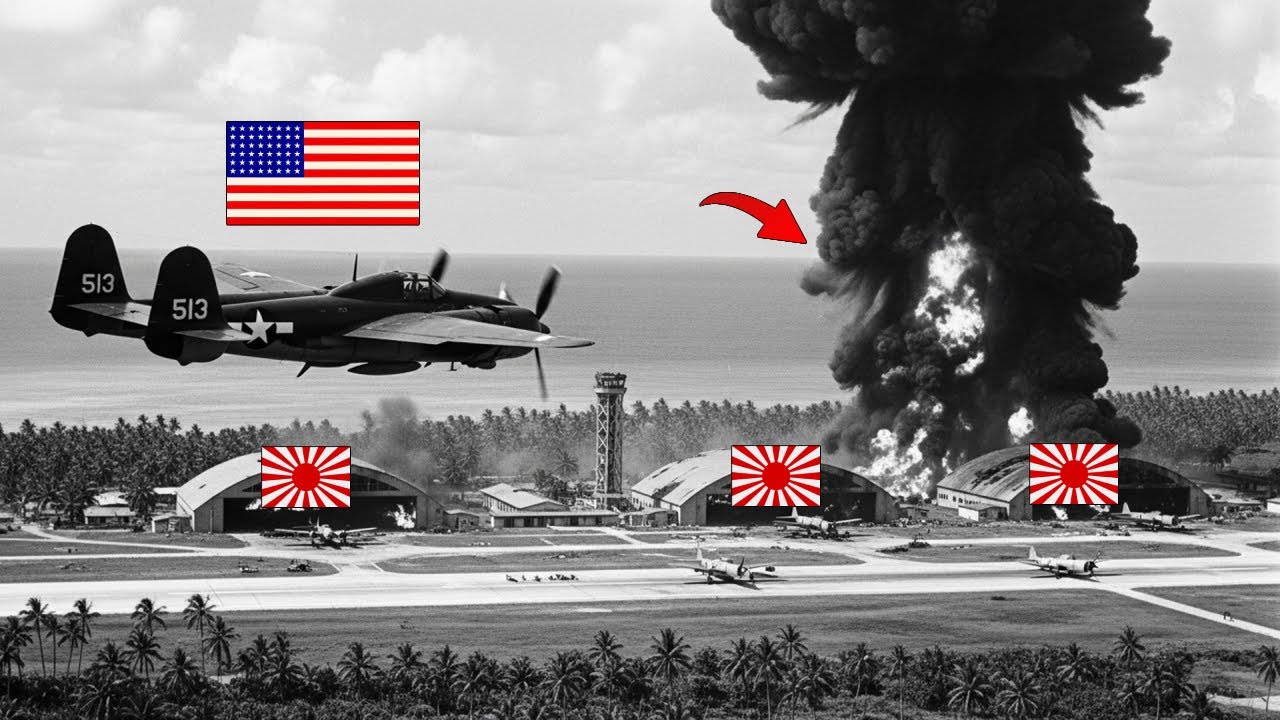

Japanese Couldn’t Believe One P-61 Was Hunting Them — Until 4 Bombers Disappeared in 80 Minutes

The Night the Sky Went Blind: Major Carol Smith and the Black Widow’s Unseen War

At 23:40 on December 29th, 1944, the air over Morotai—a scraped-out island airbase north of the Philippines—was the kind of darkness pilots remembered for the rest of their lives. No moon. No stars. Clouds thick enough to swallow an airplane whole. The black was so complete that even seasoned airmen felt their instincts rebel. Humans weren’t built to fight in a void.

Major Carol C. Smith sat hunched in the tight cockpit of his P-61 Black Widow, listening to the quiet, lethal language of instruments. He was only 26 years old, but the numbers behind his name already carried weight: 43 combat missions, four confirmed kills, and a reputation for staying calm when the sky stopped making sense.

Behind him, in a separate compartment, his radar operator, Lieutenant Philip Porter, stared into a glowing scope that turned darkness into geometry. A blip moved steadily across the screen: 180 knots, north of the Philippine Islands, heading toward Morotai’s growing airfields.

It wasn’t just another contact.

It was part of a pattern that had been strangling the island for two weeks.

Fourteen nights of alarms

For 14 days, Japanese bombers had attacked Morotai nearly every night. The result wasn’t just exhaustion—it was erosion. 334 air raid alerts in two weeks meant men sleeping in their boots, engineers working with one eye on the sky, construction crews learning to flinch at the first hint of an engine note.

And construction mattered.

American engineers were building two airfields to support the coming invasion at Lingayen Gulf. If American fighters could operate from Morotai, they could cover the invasion force—protect transports, hunt Japanese aircraft, and choke off counterattacks before they reached the beachheads.

The Japanese understood exactly what those airfields meant.

So they tried to erase them before they could become real.

They sent bombers. Conventional raiders. Desperate one-way aircraft loaded with explosives. Anything that could turn runways into craters and tents into funerals. Every bomb that got through could mean dead engineers, delayed airfields, and a delayed invasion—translated into the only arithmetic war ever truly respects: more casualties.

The 418th Night Fighter Squadron had arrived only three days earlier, on December 26th. They were new to Morotai, new to its weather, new to its rhythms—and they were, for the moment, the thin line between sleeping tents and falling bombs.

That pressure didn’t roar. It pressed.

It pressed in the silence before takeoff, in the sweat inside a flight helmet, in the knowledge that even one mistake could become a crater full of men.

The airplane built for a world without sunlight

Smith’s aircraft was not like the fighters most people imagined. The Northrop P-61 Black Widow was the first American aircraft designed specifically for night combat. It was large—66 feet of wingspan—with twin Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines that could shove it fast enough to intercept bombers in the dark.

But the P-61’s real weapon wasn’t the four 20mm cannons in its belly.

It was the thing the Japanese didn’t know existed.

The SCR-720 radar, mounted in the nose, could detect aircraft miles away in complete darkness. While Japanese bombers relied on night as camouflage—believing black skies meant invisibility—the P-61 hunted by something colder than sight.

It hunted by return signals.

Microwave pulses went out. Reflections came back. On Porter’s scope, enemy aircraft were no longer invisible. They were points—movements—data.

It meant one terrifying truth: the night no longer belonged to whoever hid best. It belonged to whoever could measure.

The cruel math of twelve bombers

That night, intelligence said the Japanese had sent twelve bombers toward Morotai. Smith and Porter had one aircraft, one fuel load, one crew, and the brutal geometry of interception.

Even if Smith shot down three or four bombers, the rest could still reach the airfields. And bombers didn’t need perfect accuracy; they needed only to arrive.

Night fighting training existed because night fighting was uniquely unforgiving. No horizon. No clear visual cues. Just instruments, radar returns, and the constant fear that the target you’re closing on might be friendly.

Smith had trained for this in Florida—radar intercept procedures, night navigation, gunnery in darkness—because in the night-fighter world, competence wasn’t a luxury. It was survival.

But training didn’t change the problem: twelve bombers were coming, and time was a fuel gauge.

At 23:42, Porter spoke into the intercom. He had four separate contacts on his scope, all heading south toward Morotai, all at different altitudes.

Four targets in the dark.

Smith made a choice that would define the next hour: he would try to intercept them all.

Not because it would look good in a report.

Because if he didn’t, men would die on the ground.

First kill: the enemy that never saw him

Smith pushed the throttles forward and climbed as Porter called vectors. Heading. Altitude. Range. Corrections in degrees and feet. It sounded clinical, but it wasn’t. In a sky with no references, those numbers were the only thing holding the aircraft to reality.

The contact resolved into a Mitsubishi G4M, the “Betty”—a bomber with range and payload, but infamous for one weakness: no self-sealing fuel tanks. A few 20mm shells in the wrong place could turn it into a moving torch.

Smith closed. Two miles. One. He still couldn’t see it.

At around 500 yards, the bomber finally appeared as a darker shape against slightly less dark cloud. The exhaust flames were faint, almost shy—tiny orange whispers that betrayed a crew that believed it was alone.

Smith slid in below and behind. He centered the bomber in his gunsight.

At 350 yards, he fired a short, concentrated burst.

For two seconds, red tracers stitched the darkness. The Betty’s wing erupted. Fuel ignited instantly. The bomber rolled and dove, burning hard enough to light the clouds beneath it.

It hit the water eight miles north of Morotai at 23:57.

One down. Eleven somewhere in the black.

Smith checked his fuel. He’d burned more than he wanted already.

Night combat wasn’t only about shooting. It was about whether the plane could still get home.

Second kill: the geometry tightens

At 00:14, Porter found the second contact. It was far from the first—night interception demanded constant repositioning, five-minute dashes that ate fuel while the enemy crept closer to the airfields.

Smith pushed the Black Widow faster, knowing every minute at high power cost him patrol time. If he delayed, the bomber could reach the target zone, and anti-aircraft gunners would open fire—an outcome that might still allow the enemy to drop bombs.

Smith needed clean kills, quickly.

Another Betty appeared at a mile. Smith repeated the approach: below, behind, close enough to ensure his burst mattered.

He fired. The bomber ignited, both engines burning, and it dropped into the ocean at 00:19.

Two down.

And now the fuel gauge became a threat of its own.

Third kill: the bomber that fought back

Two remaining contacts were closer to Morotai now, at different altitudes. Smith chose the higher target first. It was a decision made in seconds, with consequences measured in craters.

At 9,000 feet, Porter locked onto a contact moving faster than the Betty and maneuvering—turning, changing altitude, refusing to fly straight and level like a victim.

This was a Nakajima Ki-49, the “Helen.” Faster, tougher, and with a tail gunner that could punish any pilot who came in lazy and direct.

Smith adjusted. Instead of dead astern, he came from below and to the left—into the bomber’s weaker coverage.

The Helen’s tail gunner opened fire first. Tracers streaked past Smith’s canopy, proof the surprise was gone.

Smith couldn’t wait for a perfect solution. He needed the shot.

A three-second burst—longer than he wanted, but necessary as the bomber maneuvered. The shells punched through. The right engine exploded. The Helen rolled inverted and fell, spinning, burning, hitting the water at 00:29.

Three down.

Smith’s fuel dropped below what most pilots would consider safe.

The fourth bomber and the edge of the margin

The last contact was low—4,000 feet—and now dangerously close to Morotai. Searchlights swept near the airfields, thin white blades cutting the sky, waiting for something to catch.

Smith descended, conserving fuel in the dive. Another Betty, flying straight toward the target zone as if nothing in the world could reach it.

Smith had one real chance. He couldn’t afford a miss.

At 00:34, he fired a short burst. The shells converged on the bomber’s center fuselage. The wing structure failed. Fuel ruptured. Fire spread like a fast decision.

The bomber hit the water at 00:35.

Four bombers destroyed in roughly an hour. And in that hour, Smith and Porter had done what the Japanese raids were designed to prevent: they had kept Morotai’s airfields alive long enough to become inevitable.

But the night still wasn’t finished with them.

The contact between him and home

On the way back, with fuel sliding toward the red, Porter called out a new radar contact at 00:42—between Smith and the airfield.

Smith had to decide whether to gamble what little fuel he had left.

If it was a bomber and he ignored it, men might die on the ground.

He turned toward it.

At 800 yards, he saw what it was: not a bomber, but a fighter—Nakajima Ki-84 “Frank.” Fast, lethal, one of Japan’s best. In daylight, it could outfight a P-61.

But it was not daylight.

And the Frank pilot had no radar.

He was searching blind in a world that had removed all visual certainty. Smith approached from behind with the same cold method: close, align, fire.

He committed to a longer burst.

The Frank’s engine erupted. Black smoke poured out. The pilot bailed out at about 3,000 feet, a white parachute blooming briefly against the black sky. The fighter slammed into the ocean at 00:46.

Five kills in a single night—four bombers and a fighter—achieved not through bravado, but through teamwork and timing.

Now Smith had to do the most dangerous thing he would do all night:

Land.

The runway disappears

Morotai’s Maguire Field was new, barely established, with minimal lighting. Pilots at night relied on simple lamps marking the runway. Without them, there was no reference—no safe way to judge height, descent rate, or touchdown point.

Smith approached with fuel thin enough to make every power change feel expensive.

Then, at 00:55, the runway lights went out.

All of them.

Instantly.

Smith was only miles out. Too low on fuel to divert. Too committed to climb and circle. The choices collapsed into a single hard line: land blind, or crash into the ocean and pray.

He used the radar altimeter, the compass heading, dead reckoning—tools meant to assist, now forced to replace sight entirely. Gear down. Flaps full. Speed held above stall with almost no margin.

At 00:59, the P-61 hit crushed coral hard enough to jolt the crew, but the landing gear held. Smith braked until the aircraft stopped, unsure whether he was centered on the runway or inches from disaster.

By the time ground crew reached him with flashlights, he had only a few minutes of fuel left.

Smith climbed out shaking—not from fear, but from the body’s delayed payment for an hour of pure concentration. Porter followed him out. The night’s victories belonged to both of them. Night fighting was never a solo act; it was pilot and radar operator moving as one mind.

And on Morotai, that night, the sky learned something permanent:

Darkness wasn’t protection anymore.

Not when someone could see with math.