They Called It “Suicide Point” — Until This Marine Shot Down 12 Japanese Bombers in One Day

Suicide Point, July 4, 1943: The Morning the Sky Started Falling

At 0900 on July 4th, 1943, the first thing Private First Class Evan Evans noticed wasn’t the engines.

It was the way the clouds looked broken—as if the sky itself had been shelled. Over Rendova Island, dawn rarely arrived cleanly. The air smelled like wet rot and diesel. The ground was a sponge of mud and coral grit. Every boot sank. Every breath tasted like mildew and cordite.

Evans crouched behind sandbags at a place the Marines had started calling Suicide Point—half joke, half warning, and fully accurate. Two days earlier, the same beach had burned so hard that men ran through fire to reach wounded comrades and didn’t come back. Evans had watched fuel dumps explode. He’d watched ammunition “cook off” for hours, popping and detonating like the island was still being bombed long after the planes had left. He’d watched a field hospital take hits while men waited for evacuation, and he’d learned the most important lesson the Pacific could teach: the enemy didn’t have to win to make you feel helpless.

Now, through a ragged opening in the clouds over Blanche Channel, he saw them.

Not one. Not two.

A line of Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers, dark crosses in the sky, appearing like a bad memory returning with reinforcements.

Evans was 22 years old, three weeks into this muddy hell, and he had zero aircraft shot down. That number mattered more than pride. It meant one thing: he hadn’t figured out how to stop them yet.

And in the Pacific, if you couldn’t stop them, you buried your friends.

The raid that made “Suicide Point” a name

Rendova was supposed to be a stepping stone—an artillery platform from which American guns could pound Japanese positions on New Georgia. The mission sounded simple on paper: land, build up supplies, protect the beachhead, keep the big guns firing.

But paper didn’t account for the Japanese doing what the Japanese did best in 1943: striking with speed, coordination, and cruelty.

On July 2nd, the island took a raid so sudden and violent it seemed to erase time. Radar had been knocked offline earlier. There was no real warning, no clean scramble, no orderly response. The bombers came in low over the water and hit the places that mattered: fuel, ammunition, medical stations. Places that couldn’t run. Places that couldn’t hide.

Men died because they were standing in the wrong place when the sky broke open.

Evans and his crew fired 32 rounds that day and hit nothing. That’s what made it worse. It wasn’t just loss—it was impotence. Watching the enemy do what he wanted while you pulled your trigger and changed nothing.

That night, the battalion’s leadership didn’t comfort anyone. There was no speech about honor. No promise of relief.

Just the cold truth: the Japanese would come back, and the radar parts wouldn’t arrive for days.

For a moment—only a moment—Suicide Point had lived up to its name.

The weapon that didn’t matter until it did

Evans served on a 90mm M1 anti-aircraft gun, a massive, brutal piece of steel that looked like it belonged to a different war: heavy, mechanical, indifferent. It weighed tons. It could throw a shell high enough to reach bomber altitude. It could fire fast enough to fill the sky with fragments.

On paper.

In reality, without radar, it didn’t matter what the gun could do. You couldn’t shoot what you couldn’t track. And a Betty bomber at speed didn’t give a human eye time to solve the problem. A bomber could cross miles in seconds. Mechanical calculators and binoculars weren’t built for targets that moved like that.

The gun wasn’t the issue.

Information was.

And on Rendova, information had just been murdered.

So Evans did the only thing a man can do when the world stops making sense: he worked.

He cleaned the gun until 0300, scrubbing metal until his fingers went numb, not because cleaning would stop bombs but because cleaning was a form of control. If the Japanese came again, he wanted at least one thing to be ready.

The rain on July 3rd turned Rendova into a swamp. Men stood guard in water up to their knees. Supplies rotted where they lay. But the weather brought one small mercy: Japanese aircraft didn’t love heavy storms.

That lull—brief, fragile—gave the Marines time to salvage and repair.

By dawn on July 4th, the radar operators reported something that sounded like a miracle in a place that didn’t believe in miracles:

Their SCR-268 radar was operational. Not perfect. Not elegant.

But alive.

The siren, the math, and the moment you choose not to run

At 0845, radar detected a large formation inbound from Rabaul: a bearing, a distance, an altitude—numbers that were more frightening than any rumor because they were real.

The formation split. One group turned toward New Georgia. Another kept coming for Rendova.

Sixteen bombers. Escort fighters in the hundreds.

The combat air patrol had been pulled away to meet a different threat. Rendova’s guns were about to face this alone.

At 0915, the air raid siren began to wail—an ugly, rising sound that turned every spine rigid. Marines sprinted for foxholes. Medics grabbed kits. Seabees abandoned crates and dove for cover. The beach emptied in seconds.

The only men who stayed upright were the gun crews.

Because if they ran, the island died.

Evans looked to the gun director, a Sperry M4 mechanical computer—an analog brain of gears and dials built to predict where a moving aircraft would be by the time a shell arrived. But even the M4 was fighting the wrong war. It was designed for optical tracking, not radar integration. Hooking it up to radar was awkward, imprecise, and sometimes maddening.

Even a good solution could be off by hundreds of meters.

A 90mm shell’s effective burst radius—what actually mattered—was smaller than that.

Which meant: to hit, you didn’t just need firepower. You needed the system to behave like a single organism.

Twelve guns. Twelve crews. Radar feeding data. Directors calculating. Fuzes set to detonate at exactly the right second. Shells rising into the sky.

In other words: you needed everyone to do everything right at the same time.

In war, that almost never happens.

When the sky turned into a machine

At 30 miles out, the order came: commence firing.

All twelve 90mm guns opened up at once.

The sound wasn’t loud. It was total. Each firing shook the air. Muzzle blasts knocked dust from sandbags. Speech became meaningless—mouths moved, but you couldn’t hear your own thoughts.

Evans fell into the rhythm his body had learned long before his mind understood it:

Load. Ram. Set fuse. Fire.

Again.

And again.

The shells rose in steady intervals—24-pound projectiles moving so fast they seemed to tear sound itself. Above the approaching formation, black bursts began to appear: flak blossoms in the sky, some too far left, some too high, some close enough to make bomber crews shift course slightly and keep coming.

Because two days earlier, the Japanese had flown through American flak and lived. They had learned to treat it as inconvenience.

Now they were about to learn the difference between noise and precision.

At around 10 miles, something changed. Not visible at first. Not dramatic.

The radar return locked cleanly on the lead bomber. The director’s gears clicked with a new confidence. The gun mount adjusted—two degrees, three degrees—tiny movements that meant everything.

Evans fired.

The shell climbed. The fuse counted down.

And eighteen seconds later, the sky erupted just ahead of the lead Betty.

The bomber flew into the blast.

Shrapnel tore into an engine. Fire bloomed. Smoke poured out. The aircraft tried to hold formation—Japanese discipline was real, even when the wing was burning—but discipline cannot negotiate with physics. Within a minute, the bomber dropped out and began to die, turning back toward the channel as if retreat could unmake what had already happened.

It didn’t.

The plane broke apart and hit the water northwest of Rendova.

One down.

Then, as if the first kill had taught the guns where to look, the flak got closer. The bursts tightened. The bomber formation flew into a cloud of black smoke and steel fragments—and when it emerged, more aircraft were trailing damage.

Another spiraled down. Another lost power. Another failed to escape.

The bombers did what frightened men do when their plan stops being safe: they released early.

Their bombs fell into empty ocean.

Geysers erupted offshore.

And for the first time since Suicide Point had been named, the island watched explosives miss and understood what that meant:

We can stop them.

The moment the enemy breaks

Formation discipline held until it didn’t.

Once a bomber formation breaks, it stops being a military instrument and becomes a crowd of individual pilots making survival decisions. Some climbed. Some turned west. Some ran back toward Rabaul. The escorts—fighters that were supposed to protect the bombers—began to disappear, unwilling to loiter in a sky that had turned lethal.

This was the real victory: not the kills, but the collapse of the attack.

Because the Japanese had come to destroy Rendova’s supply point and beachhead. Instead, the bombers dumped their payloads, ran, and died anyway.

Evans’ gun heated until it shimmered. Heat waves rose off the barrel. The crew’s hands kept moving because stopping meant thinking, and thinking meant fear.

Load. Ram. Set. Fire.

By 09:32, the ceasefire order came. The guns fell silent so suddenly the quiet felt unnatural, almost painful. Men realized they were alive only after the noise ended.

Evans stepped back from his gun and felt his hands shaking—not with terror, but with exhaustion, the delayed payment for minutes spent operating as a machine.

The numbers that emerged were almost impossible.

Of sixteen bombers, only four were still flying.

Twelve had been destroyed.

And most importantly: not one bomb hit the island.

Suicide Point had become something else.

A killing ground.

The photograph that almost didn’t exist

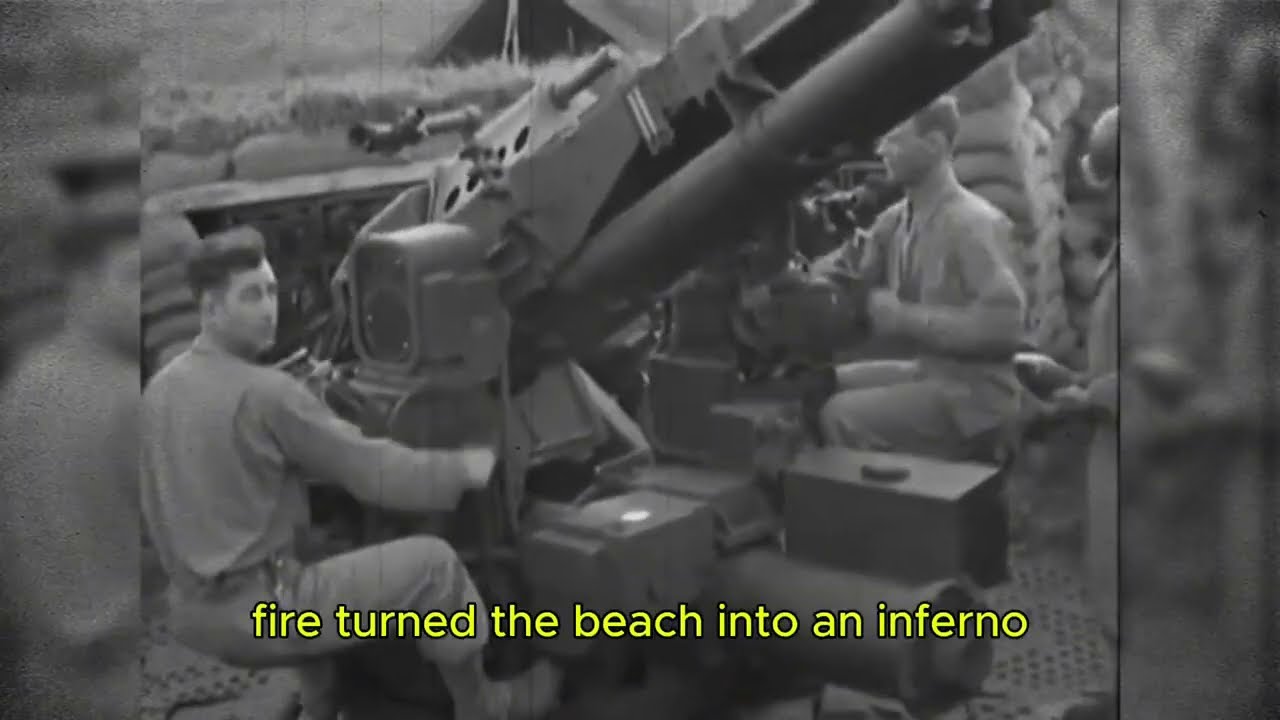

That afternoon, a combat photographer arrived. Three Marines posed beside the gun—an ordinary act that tried to make a moment feel comprehensible.

Only one photo survived the war.

Decades later, the image would be found in the National Archives, a caption attached like a quiet epitaph: one of the anti-aircraft guns which wiped out a Japanese bomber fleet…

Evans didn’t know the photo existed. Like many veterans, he assumed the world had moved on.

But history has strange ways of waiting.

Fifty years later, he wrote to an archivist, asking for any photo of the gun—just to show his grandchildren what it looked like. The archivist searched, found the image, and mailed it.

And when Evans saw himself at twenty-two beside that weapon—beside that morning—something he’d carried for decades rose up again: not pride, not glory, but the weight of a day when men fell from the sky and the living had to keep working anyway.

Why this morning mattered

Rendova wasn’t the war’s biggest battle. Evans wasn’t the most famous Marine. A 90mm crew didn’t fit the heroic mythology the way a fighter pilot did.

But that’s exactly why this story matters.

Because wars aren’t decided only by famous names. They’re decided by systems that finally work, by crews that finally sync, by exhausted men who refuse to stay helpless.

On July 4th, 1943, a place called Suicide Point learned it could defend itself. The Japanese learned that daylight raids could become suicide. And a young Marine who had hit nothing two days earlier watched his gun—and his island—change the mathematics of air defense in the Pacific.

And the most haunting part is this:

When the shells finally found their targets, the beach didn’t cheer.

It went back to work.

Because on Rendova, survival wasn’t a celebration.

It was the next task on the schedule.